The Washington Post was just one of many news sources to note a recent report provided by the National Vital Statistics System of the Centers for Disease Control, "Births: Provisional Data for 2016" (PDF format). This report noted that not only had the absolute number of births fallen, but that the total fertility rate in 2016 was the lowest it had been in more than three decades: "The 2016 total fertility rate (TFR) for the United States was 1,818.0 births per 1,000 women, a decrease of 1% from the rate in 2015 (1,843.5) and the lowest TFR since 1984." The Washington Post's Ariana Eunjung Cha noted that this fall was a consequence of a sharp fall in births among younger Americans not wholly compensated for by rising fertility rates in older populations.

According to provisional 2016 population data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Friday, the number of births fell 1 percent from a year earlier, bringing the general fertility rate to 62.0 births per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44. The trend is being driven by a decline in birthrates for teens and 20-somethings. The birthrate for women in their 30s and 40s increased — but not enough to make up for the lower numbers in their younger peers.

[. . .]

Those supposedly entitled young adults with fragile egos who live in their parents' basements and hop from job-to-job — it turns out they're also much less likely to have babies, at least so far. Some experts think millennials are just postponing parenthood while others fear they're choosing not to have children at all.

Strobino is among those who is optimistic and sees hope in the data. She points out that the fall in birthrates in teens — an age when many pregnancies tend to be unplanned — is something we want and that the highest birthrates are now among women 25 to 34 years of age.

“What this is is a trend of women becoming more educated and more mature. I’m not sure that’s bad,” she explained.

Indeed, as fertility treatments have extended the age of childbearing, the birthrates among women who are age 40 to 44 are also rising.

Total fertility rates in the United States were last this low, as noted above, in 1984, after a decade where fertility rates had hovered around 1.8 children born per woman. The United States' had sharply dropped to below-replacement fertility occurring in 1972, with a sharp increase to levels just short of replacement levels only occurring in the mid-1980s.

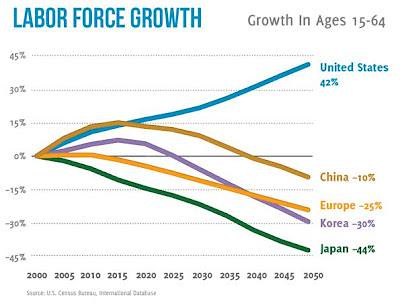

There has been much talk this past half-year about the end of American exceptionalism, or at least the end of a favourable sort of American exceptionalism. To the extent that fertility rates in the United States are falling, for instance, this may reflect convergence with the fertility rates prevalent in other highly developed societies. Gilles Pison's Population and Societies study "Population trends in the United States and Europe: similarities and differences" observed that, although the United States and the European Union saw the same sorts of trends towards lower fertility rates and extended life expectancies, the European Union as a whole saw substantially lower birth rates and lower completed fertility.

The strong natural growth in the United States is due, in part, to high fertility: 2.05 children per woman on average, compared with 1.52 in the European Union. In this respect, it is not the low European level which stands out, but rather the high American level, since below-replacement fertility is now the norm in many industrialized countries (1.3 children per woman in Japan, for example) and emerging countries (1.2 in South Korea, and around 1.6 in China). With more than two children per woman in 2005, the United States ranks above many countries and regions of the South and belongs to the minority group of highfertility nations.

Average fertility rates conceal large local variations, however: from 1.6 children per woman in Vermont to 2.5 in Utah; from 1.2 in Poland to 1.9 in France. The scale of relative variation is similar on either side of the Atlantic. In the north-eastern USA, along a strip spreading down from Maine to West Virginia, fertility is at the same level as in northern and western Europe (Figure 3). Close to Mexico, on the other hand, the “Hispanic” population (a category used in American statistics) is pushing up fertility levels. Over the United States as a whole, Hispanic fertility stands at 2.9 children per woman, versus 1.9 among nonHispanic women [4]. Between “White” and “AfricanAmerican” women, the difference is much smaller: 1.8 versus 2.0.

The highest fertility levels in the European Union are found in northern and western Europe (between 1.7 and 1.9 children per woman) and the lowest in southern, central and eastern Europe (below 1.5). Exceptions to this rule include Estonia (1.5), with higher fertility than its Baltic neighbours, and Austria (1.4) and Germany (1.3), which are closer to the eastern and southern countries.

This overall pattern seems to have endured. Why this is the case, I am uncertain. Even though the United States lacks the sorts of family-friendly policies that have been credited for boosting fertility in northern and western Europe, I wonder if the United States does share with these other high-fertility, highly-developed societies cultural similarities, not least of which is a tolerance for non-traditional families. As has been observed before, for instance at Population and Societies by Pison in France and Germany: a history of criss-crossing demographic curves and by me at Demography Matters back in June 2013, arguably the main explanation for the higher fertility in France as compared to West Germany is a much greater French acceptance of non-traditional family structures, with working mothers and non-married couples being more accepted. (West Germany's reluctance, I argued here in February 2016, stems from the pronounced conservative turn towards traditional family structures without any support for government-supported changes following efforts by totalitarianism states to do just that, first under Naziism and then in contemporary East Germany.)

It's much too early to come to any conclusions as to whether or not this fall in American fertility will be lasting. From the perspective of someone in the early 1980s, for instance, the sharp spike in American fertility in the mid-1980s that marked arguably the single most importance divergence between the United States and the rest of the highly developed world would have been a surprise. Maybe fertility in the United States will recover to its previous levels. Or, maybe, under economic pressure it will stay lower than it has been.