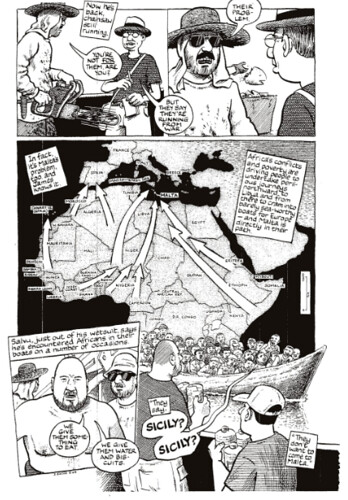

I have a Tumblr account. Tumblr is a platform that is good for sharing images and so a natural adjunct to my interest in amateur photography, but it's also a platform good for sharing--sometimes quite widely--all sorts of links, and for starting all sorts of discussions. On the weekend, I saw the below pop up on my dashboard.

This image caught my attention, not least because I was completely unaware of any such desperate and massive movement of refugees from Europe to North Africa. Yes, there were some refugee movements by Europeans to Africa, this June 2012 article in New African Magazine looking at some interesting Polish communities in East Africa, while the Greek government-in-exile was based in Cairo in an Egypt that had long been a node in the Greek diaspora. Such a large and desperate flight of refugees as indicated in the photo, though, was nothing I'd heard of before. Where would these refugees have come from? Where would they have been going?

That's when I noticed the name on the ship. "Vlora" is one rendition of the name of the Albanian port city of Vlorë. As it happens, that ship is closely associated with one massive flight of refugees, one so noteworthy that it even earned an article in Italian Wikipedia. It's just that it's a different refugee movement from the one described by the above photo's caption.

Someone, I don't know who, engaged in a bit of creative photo editing, converting the colour photo above to a black-and-white one and cropping the image somewhat. That might be justifiable on creative grounds. What is not justifiable, at all, is the lie someone chose to tell about this image, one of the iconic images from the initial mass emigration of Albanians in the early 1990s.

On August 7, 1991, Albanians boarded the Vlora in the hope of heading to Italy on its way from Cuba where it had shipped 10,000 tons of sugar. The real number of people that crammed onto the ship is unknown with some figures ranging from 10,000 to 20,000.

The ship crossed the Adriatic. As the ship approached Italian ground some fell to sea to approach Italy a moment sooner, unable to handle the crushing atmosphere aboard. Others screamed “Italia! Italia!” on the ship.

Thomas Jones also noted this particular falsification at the blog of the London Review of Books this September.

On 7 August 1991, the Albanian ship Vlora docked at the Port of Durrës, twenty miles west of Tirana, with a cargo of Cuban sugar. Thousands of people, desperate to leave Albania in the first throes of its ‘transition’ from communism, boarded the ship and prevailed on the captain to take them to Italy. The Vlora arrived in Bari the next day. According to a Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe report from January 1992:

After several hours of waiting in the port of Bari, the Italian authorities allowed the Albanians to disembark for humanitarian reasons and led them to La Vittoria Sports Stadium. As the Italian authorities started forced repatriation using military transport planes and ferries, clashes broke out between policemen and Albanians. The Albanians barricaded themselves in the stadium refusing to return to their country; some 300 succeeded in escaping.

[. . .]

Photographs of the Vlora’s passengers disembarking in Bari have been circulating on the internet this month: first with claims that they show migrants from Libya or Syria heading to Europe now; then, a few days later, with the facts, setting the historical record straight. (I was sent them by someone who thought they were Europeans bound for North Africa during the Second World War.) Falsification can turn out to be a useful reminder of the past, once you’ve identified it.

Another blog, The Cryptic Philosopher, also debunked this misrepresentation of the image in September. Still another blog, looked at a very similar image this September, including a brief documentary on the 1991 Vlora crisis. That blog noted that its variant was being used to represent Syrian refugees fleeing to Europe.

France 24, meanwhile, placed this image in the context of multiple other faked and misrepresented images used in relation to the refugee crisis.

Issues of misattribution are themselves annoying. It's even more annoying if this misattribution is intentional. It's particularly annoying if these images have gone viral. Most if not all of the various sources I encountered debunking this misrepresentation date to September, but I ran into this image entirely independent of these sources at the end of October. I did debunk them, first on Tumblr and later on Facebook, but I have no confidence that those debunkings, or this one, will put an end to the various misrepresentations of the 1991 image of the Vlora. This is a shame: It's already difficult enough to talk about issues without falsehoods confusing the issue.