Demographics writer Jonathan Last (

Wikipedia article, official site) has gotten a fair bit of attention for his

Wall Street Journal essay

"America's Baby Bust", wherein he argues that the United States' slowing economy is directly connected to low fertility. Much of the reaction to his analysis has been critical.

Writing in The New Republic, Rui Texeira questions Last's dismissal of immigration and his piecemeal remedies for low fertility (tax breaks as opposed to government programs). It's taken apart

scathingly by Love, Joy, Feminism!'s Libby Anne, who rightly finds Last's equation of Chinese forcible one-child policy with small American families ridiculous, Last's dismissal of the idea that things could be done to make family life easier on the grounds that people shouldn't necessarily expect happiness ill-guided, and makes an argument that Last's focus on fertility of well-off white American women reflects the

"race suicide" rhetoric of early 20th century American eugenicists.

Me, I'd like to take a look at a

Los Angeles Times op-ed that got published on the 8th of February, simply titled "Fertility and Immigration". I think this to be one of those articles that could benefit from a

fisking.

In Washington, politicians are trying to reform America's immigration system, again. Both President Obama and Republican Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) are proposing "paths to citizenship" for an estimated 11 million illegal immigrants. Other proposals abound, including finishing the border fence, creating a better E-Verify system for employers and passing the last Congress' Dream Act.

All of these ideas, however, fundamentally misunderstand immigration in America: Future immigration is probably going to be governed not by U.S. domestic policy choices but by global demographics.

1. In Last's defense, he does say "probably".

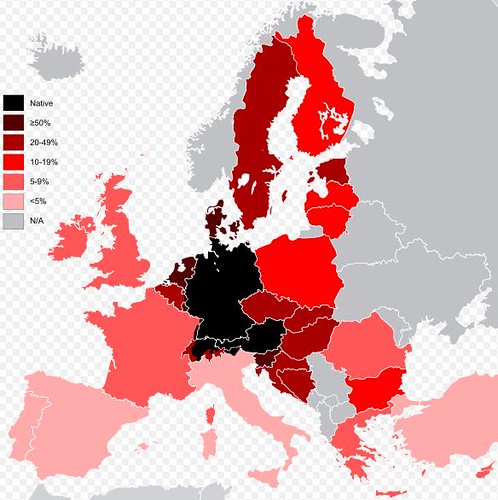

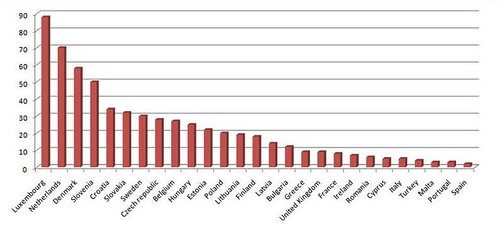

2. Against Last, he really does overlook the importance of policy in determining major migration flows. Consider the movement of Poles to Germany. Large-scale Polish migration west dates back to the beginning of the

Ostflucht, the migration of Germans and Poles from what was once eastern Germany to points west, in around 1850. By the time Poland regained its independence in 1919, hundreds of thousands of Poles lived in Germany, mainly in the Ruhr area and Berlin. Leaving aside the exceptional circumstances of the post-Second World War deportations of Germans from east of the Oder-Neisse line, Polish migration to (West) Germany

continued under Communism, as hundreds of thousands of people with German connections--ethnic Germans, members of Germanized Slavic populations, and Polish family members--emigrated for ethnic and economic reasons. In the decade of the 1980s,

up to 1.3 million Poles left the country, the largest share heading for Germany. Large-scale Polish migration to Germany has a long history.

And yet, in the past decade, by far the biggest migration of Poles within the European Union was directed not to neighbouring Germany but to a United Kingdom that traditionally hasn't been a destination. Most Polish migration to Germany, it seems, is

likely to be circular migration; Germany

missed out on a wave of immigrants who would have

helped the country's demographics significantly. Why? Germany chose to keep its labour markets closed for seven years after Poland's European Union admission in 2004, while the United Kingdom did not, the results being (among other things) that

Polish is the second language of England.

Regulations matter. I've

already noted that in Mediterranean Europe, the large majority of immigrants don't come from North Africa, notwithstanding reasonably strong trans-Mediterranean ties. Why? Restrictive migration policies. Other examples can be easily found. Migration to different countries occurs largely at the will of different countries. There are no hordes battering down the doors.

For the last 30 years, a massive number of immigrants has poured into the U.S. from south of the border. Today there are 38 million people living in the United States who were born somewhere else. That's an average of more than 1 million immigrants a year for three decades, a sustained influx unlike any we've seen before in U.S. history. And regardless of what policies Washington decides on, that supply is likely to dry up soon.

[. . .]

When it comes to immigration, demographers have a general rule of thumb: Countries with fertility rates below the replacement level tend to attract immigrants, not send them. And so, when a country's fertility rate collapses, it often ceases to be a source of immigration.

1. That's not a hard-and-fast rule. Looking to the post-Second World War era, for instance, even though fertility rates in North America and western Europe were substantially above replacement levels, these regions still attracted large numbers of immigrants. Why? Simply put, economic (and political) conditions in these countries were sufficiently attractive to migrants, who could easily find work.

2. A collapsing fertility rate does not mean a country stops being a source of immigration. Look at post-Communist Europe, if you don't believe me. Now, it

is true that if fertility falls to low levels and stays at low levels, the size of the cohorts of potential emigrants will eventually shrink. I don't think it a coincidence that Romania has emerged as a source of immigrants as the cohort of children born under Ceaucescu's pro-natalist policies comes of age. That shrinkage by itself does not mean a diminished propensity to migrate, however. Look, again, at Romania. The ability to migrate, whether we're talking about being able to afford the various costs and benefits of the movement or the non-existence of barriers to migrate (or even the existence of incentives

to migrate is more substantial a factor than the mere presence of a cohort of people of which some may become potential migrants.

Consider Puerto Rico. In the 1920s, Puerto Ricans began to trickle into the United States. Their numbers accumulated slowly, and by 1930, there were 50,000 Puerto Ricans living in the U.S. (nearly all in New York City). Over time, however, the community reached a critical mass, and by the mid-1940s, 30,000 Puerto Ricans were arriving every year. The Puerto Rican wave continued, and grew. In 1955, 80,000 Puerto Ricans came to the United States.

But from 1955 to 2010, the number plummeted. Even though the population of Puerto Rico had nearly doubled in that time, the total number of Puerto Ricans moving to the United States in 2010 was only 4,283.

Why? After all, migrating to the United States from Puerto Rico had become easier, not harder. And while economic conditions in Puerto Rico brightened somewhat, the opportunities and standard of living in the U.S. are still superior.

What happened is that Puerto Rico's fertility rate imploded. In 1955, Puerto Rico's total fertility rate was 4.97, well above replacement. By 2012, it had fallen to 1.64 — even further below the replacement line than the United States'.

I went to the

Penn World Tables and pulled data on Puerto Rico for the 1950-2011 period.

"Brightened somewhat" is faint praise indeed for the Puerto Rican economic miracle. PPP-adjusted GDP per capita in Puerto Rico rose from a shade over 18% of the United States average in 1950 to 58-59% in 2010, depending on the exact method used. It grew by 250% in the two decades after 1950, experienced a brief regression and slow recovery in the 15 years subsequent, and since 1985 has continued to converge notably. All this economic growth has come has the population of Puerto Rico has almost doubled, and as the American economy has of course continued its own growth.

Living standards in Puerto Rico have risen hugely. If they hadn't, and all things remained the same, Puerto Ricans would still be leaving their island for the United States in very large numbers. Total numbers might be smaller, but the propensity to leave would not have diminished palpably.

Many Latin American countries have already fallen below the replacement level. It's not a coincidence that sub-replacement countries — such as Uruguay, Chile, Brazil and Costa Rica — send the U.S. barely any immigrants at all. The vast majority of our immigrants come from above-replacement countries, such as Honduras, El Salvador, Colombia, Guatemala and Mexico.

One thing that Last seems to have overlooked completely is that the countries with sub-replacement fertility in Latin America that he named are (by and large) not only the more economically developed countries in Latin America and therefore would be less likely to send migrants than less developed ones, but that these countries have ties outside of Latin America to countries other than the United States. (The small republics of Central America and the Caribbean are quite poor, and are almost as dependent on the United States in many ways as, oh, Puerto Rico. Mexico is the exception, mainly because Mexico borders directly on the United States. If it didn't, there would not be somewhere in the area of forty million people of Mexican background in that country.)

For instance, Last says that there aren't many Brazilians in the United States. That's true; as the Burgh Diaspora's Jim Russell

recently noted, many Brazilian migrants are returning to their country. That said,

Brazilian emigration is overwhelmingly not concentrated on the United States. There are at least as many Brazilians living in Japan as in the United States, and more Brazilians living in western Europe. The United States is not the world.

Consider Mexico, which over the last 30 years has sent roughly two-thirds of all the immigrants — legal and illegal — who came to the United States. In 1970, the Mexican fertility rate was 6.72. Today, it's hovering at the 2.1 mark — a drop of nearly 70% in just two generations. And it's still falling.

The result is that from 2005 to 2010, the U.S. received a net of zero immigrants from Mexico.

Stricter border control has, of course, played no role in this.

Last is right to note that the global demographic transition will diminish numbers of potential migrants. He is wrong to conclude that it will diminish the propensity of people to migrate, and doesn't take into consideration the critical role of public policy in either enabling or disabling flows of migrants. Give it a C minus.