A recent post at Goldman's Asia Times blog Inner Workings, "Southern Europe: Hopeless But Not Serious", takes a look at the PIIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, Spain) and their dire economic future. The dire future of all of them save Ireland, mind; ultra-low fertility and rapid aging will do the rest in.

That is true for the moment, when the elder dependent ratio for Southern Europe stands at around 25%. Between 2020 and 2045, however, the infertility of Southern Europe will catch up with it, and the elder dependent ratio will rise to over 60%–an impossible, unmanageable number. At that point the character of these countries will change radically; they will be overwhelmed with immigrants from North Africa as well as sub-Saharan Africa, who will not have the skills or the habits of civil society to maintain economic life. And their economies will slide into a degree of ruin comparable only to that of classical antiquity. Perhaps the Chinese will operate Greece as a theme park. Spain, which can draw on Latin American immigrants, is likely to be the least badly off.

Strictly speaking, Ireland should not be included among the PIIGS (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, Spain). Although post-Catholic Ireland has lost its famous fecundity, Ireland’s fertility rate still hovers around replacement. The Irish economy was far too dependent on offshore finance as a source of employment and suffered disproportionately from the collapse of the credit bubble in 2008. But this small country also has high-tech manufacturing and other industries which make the eventual restoration of prosperity possible. The southern Europeans are doomed. They have passed a demographic point of no return. There simply aren’t enough females entering their child-bearing years in those countries to reverse the rapid aging.

I wouldn't necessarily disagree with much of this. The rapid aging of southern Europe's populations and the shrinkage of the cohorts of youth, combined with the effects of the internal devaluation given the region's adoption of the Euro, and a general lack of economic competitiveness, does augur bad things. Edward Hugh has written about the very low trend economic growth rate in Italy (Portugal in passing, too). Absent very unlikely transformations in southern European demographic profiles, things can be problematic. I also think Goldman is right to suggest that Spain, with its well-established links with Latin America, may avoid many of the worst effects.

Where do I disagree? My lesser disagreement relates to the ways in which the effects of population aging may well be mitigated by better health. We've written in the past about longevity, exploring the ways in which longevity is being extended. The intriguing concept of "disability-free life expectancies" may provide a potentially very useful paradigm.

[M]any people over 65 are not in need of the care of others, and, on the contrary, may be caregivers themselves. The authors provide a new dependency measure based on disabilities that reflect the relationship between those who need care and those who are capable of providing care, it is called the adult disability dependency ratio (ADDR). The paper shows that when aging is measured based on the ratio of those who need care to those who can give care, the speed of aging is reduced by four-fifths compared to the conventional old-age dependency ratio.

Co-author Dr.Sergei Scherbov, from IIASA and the VID, states that “if we apply new measures of aging that take into account increasing life-spans and declining disability rates, then many populations are aging slower compared to what is predicted using conventional measures based purely on chronological age.”

The new work looks at “disability-free life expectancies,” which describe how many years of life are spent in good health. It also explores the traditional measure of old age dependency, and another measure that looks specifically at the ratio of disabilities in adults over the age of 20 in a population. Their calculations show that in the United Kingdom, for example, while the old age dependency ratio is increasing, the disability ratio is remaining constant. What that means, according to the authors, is that, “although the British population is getting older, it is also likely to be getting healthier, and these two effects offset one another.”

The new ratio that Sanderson and Scherbov introduce, of the ratio of disabilities in adults over the age of 20 in a population, does seem to make more sense in certain contexts notwithstanding a degree of subjectivity (what will different statistical agencies define as "disabilities"). If this ratio is adopted and if the prediction that most children born today in developed countries will reach the century mark comes true, if there are sufficient reforms conceivably southern Europe might avoid catastrophe. ("If", as the Spartan king said to the Persian ambassador.)

My greater disagreement? His predictions of Eurabian doom: "[T]he character of these countries will change radically; they will be overwhelmed with immigrants from North Africa as well as sub-Saharan Africa, who will not have the skills or the habits of civil society to maintain economic life."

No, no, no.

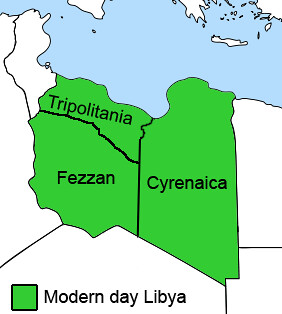

Let's begin by noting that trans-Mediterranean immigration plays a minor role in southern Europe. Of themore than four million immigrants in Spain, only a bit more than a half-million are Moroccan, with insignificant if high-profile numbers of immigrants from elsewhere in the Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa. Back in 2006 I noted that there were half again as many eastern European immigrants in Italy as from Africa, and that African immigrants were as numerous as the combined total of Latin American and Asian immigrants. Immigrants in Portugal are overwhelmingly from the Lusophone world and eastern Europe, and of the million-odd immigrants in Greece a large majority are immigrants from neighbouring Albania. There may be large income gaps between the northern and southern shores of the Mediterranean, but income gaps in themselves do not produce immigration. All manner of ties, including human ties, gird immigration, and all of these southern European countries are regional economic and cultural powers, if not global ones (Spain comes particularly to mind, to a lesser extent Italy, Portugal via its Lusophone connections, and Greece relative to impoverished Albania). Why would geography determine everything? It clearly doesn't.

Still more importantly, if we accept Goldman's argument that southern Europe is doomed to impoverishment--easy enough to belief, especially if economic pressures lead to a sustained large emigration of youth from southern to northern Europe--why would immigrants even settle in southern Europe in large numbers? By global standards, Latvia is quite wealthy, and its aging and shrinking population could arguably benefit from immigrants and provide them with sufficient wages. Are large numbers of immigrants settling in Latvia? No: Latvia's economy is too unstable, and arguably lacking enough long-term prospects for various reasons including a contracting workforce and aging population, to keep Latvians at home, never mind attract immigrants. At most, Latvia is/will be a transit country for migrants hoping to make it to rich western Europe.

Back to southern Europe. Migration is fundamentally a rational decision, made by people who want to extract the maximum benefit from their movement from one place to another. If migrants have to decide between a declining southern Europe and a more prosperous northern Europe, I'd bet they'd prefer northern Europe. I know what decision I'd make. You? Even if--if--there are substantially greater flows of North Africans to Europe and of sub-Saharan Africans beyond North Africa, why would they settle in large numbers in countries lacking in any long-term prospects?

Everyone reading this blog and writing here--indeed, everyone interested in demographics generally--likely agrees that migration is a very important phenomenon in the 21st century world. Everyone should also take care not to make the sorts of dramatic predictions of radical clash-of-civilization-themed transformations that never come true, too. Demography matters too much for it to be treated so superficially.