- La Presse notes that suburbanization proceeds in Montréal, as migration from the island of Montréal to off-island suburbs grows. This is of perhaps particular note in a Québec where demographics, particularly related to language dynamics, have long been a preoccupation, the island of Montréal being more multilingual than its suburbs.

- The blog Far Outliers has been posting excerpts from The Epic City: The World on the Streets of Calcutta, a 2018 book by Kushanava Choudhury. One brief excerpt touches upon the diversity of Calcutta's migrant population.

- The South China Morning Post has posted some interesting articles about language dynamics. In one, the SCMP suggests that the Cantonese language is falling out of use among young people in Guangzhou, largest Cantonese-speaking city by population. Does this hint at decline in other Chinese languages? Another, noting how Muslim Huiare being pressured to shut down Arabic-medium schools, is more foreboding.

- Ukrainian demographics blogger pollotenchegg is back with a new map of Soviet census data from 1990, one that shows the very different population dynamics of some parts of the Soviet Union. The contrast between provincial European Russia and southern Central Asia is outstanding.

- In the area of the former Soviet Union, scholar Otto Pohl has recently examined how people from the different German communities of southeast Europe were, at the end of the Second World War, taken to the Soviet Union as forced labourers. The blog Window on Eurasia, meanwhile, has noted that the number of immigrants to Russia are falling, with Ukrainians diminishing particularly in number while Central Asian numbers remain more resistant to the trend.

- Finally, JSTOR Daily has observed the extent to which border walls represent, ultimately, a failure of politics.

Showing posts with label ethnicity. Show all posts

Showing posts with label ethnicity. Show all posts

Friday, March 01, 2019

Some news links: Montréal & Calcutta migration, Chinese languages, former Soviet Union, borders

Labels:

canada,

central asia,

china,

cities,

ethnicity,

former soviet union,

india,

language,

links,

migration,

russia,

south asia,

ukraine

Thursday, February 14, 2019

Some news links: history, cities, migration, diasporas

I have some links up for today, with an essay to come tomorrow.

- JSTOR Daily considers the extent to which the Great Migration of African-Americans was a forced migration, driven not just by poverty but by systemic anti-black violence.

- Even as the overall population of Japan continues to decline, the population of Tokyo continues to grow through net migration, Mainichi reports.

- This CityLab article takes look at the potential, actual and lost and potential, of immigration to save the declining Ohio city of Youngstown. Will it, and other cities in the American Rust Belt, be able to take advantage of entrepreneurial and professional immigrants?

- Window on Eurasia notes a somewhat alarmist take on Central Asian immigrant neighbourhoods in Moscow. That immigrant neighbourhoods can become largely self-contained can surprise no one.

- Guardian Cities notes how tensions between police and locals in the Bairro do Jamaico in Lisbon reveal problems of integration for African immigrants and their descendants.

- Carmen Arroyo at Inter Press Service writes about Pedro, a migrant from Oaxaca in Mexico who has lived in New York City for a dozen years without papers.

- CBC Prince Edward Island notes that immigration retention rates on PEI, while low, are rising, perhaps showing the formation of durable immigrant communities. Substantial international migration to Prince Edward Island is only just starting, after all.

- The industrial northern Ontario city of Sault Sainte-Marie, in the wake of the closure of the General Motors plant in the Toronto-area industrial city of Oshawa, was reported by Global News to have hopes to recruit former GM workers from Oshawa to live in that less expensive city.

- Atlas Obscura examines the communities being knitted together across the world by North American immigrants from the Caribbean of at least partial Hakka descent. The complex history of this diaspora fascinates me.

Monday, March 14, 2016

Some followups

For tonight's post, I thought I'd share a few news links revisiting old stories

- The Guardian notes that British citizens of more, or less, recent Irish ancestry are looking for Irish passports so as to retain access to the European Union in the case of Brexit. (Net migration to the United Kingdom is up and quite strong, while Cameron's crackdown on non-EU migrants has led to labour shortages.

- NPR notes one strategy to get fathers to take parental leave: Have them see other fathers take it.

- Reuters notes that the hinterland of Fukushima, depopulated by natural and nuclear disaster, seems set to have been permanently depopulated. Tohoku

- Bloomberg noted that East Asia's populations are aging rapidly, another article noting how Japan's demographic dynamics are setting a pattern for other high-income East Asian economies.

- In Malaysia, the Star notes that low population growth among Malaysian Chinese will lead to a sharp fall in the Chinese proportion in the Malaysian population by 2040.

- Coming to Alberta, CBC notes how the municipality of Fort McMurray has been hit very hard by the end of the oil boom, as has been Alberta's largest city and business centre of Calgary.

- On the subject of North Korea and China, The Guardian wrote about the stateless children born to North Korean women in China, lacking either Chinese or North Korean citizenship.

- The Inter Press Service notes that, as the Dominican Republic cracks down on Haitian migrants and people of Haitian background generally, women are in a particular situation.

- IWPR provides updates on Georgia's continuing and ongoing rate of population shrinkage, a consequence of emigration.

- On the subject of Cuba, the Inter Press Service reported on Cuban migrants to the United States stranded in Latin America, while Agence France-Presse looked at the plight of Cuba's growing cohort of elderly.

Labels:

ageing,

alberta,

china,

cuba,

demographics,

east asia,

ethnicity,

european union,

fertility,

georgia,

haiti,

ireland,

japan,

korea,

latin america,

malaysia,

migration,

united kingdom,

united states

Wednesday, November 18, 2015

On the ineffective and immoral proposal of David Frum

A recent post by Shakezula at Lawyers, Guns and Money Canadian-born American political commentator David Frum posted to his Twitter account a proposal to deal with terrorism in Europe.

Alas, subsequent posts on his Twitter feed make it unlikely that this was a proposal he was offering forth in the noble tradition of Jonathan Swift.

There are many things that can be said about this proposal. Perhaps the most important, at least from the perspective of practicality, is that it wouldn't work. Most of the perpetrators were in Europe more than two years ago, many seem in fact to have been native-born citizens of one European country or another (France and Belgium). Are we to broaden the scope of this mass deportation--what some, perhaps unfavourable to this cause, might call an ethnic cleansing? How far back shall we go? Who shall determine who gets to stay? Do people of Muslim ancestry in Europe itself, like Bosniaks and Albanians, get to stay? Shall we also include converts? What legal mechanisms will be established to enable mass deportations of sufficient scope, whatever sufficient is?

Moving on from issues of practicality, Frum's proposal is inhumane, and this inhumanity would make things worse. It's difficult to see how any effort at a mass deportation of European residents, including European citizens, based on their religion would not end catastrophically for everyone involved, not least by legitimating the Daesh's rhetoric of an inevitable clash between Christians and Muslims worldwide.

Pew Research Centre's statistical overview of European Muslim populations is worth noting, if you want some quick statistics. What better place to start than with actual data?

Wednesday, June 17, 2015

On the upcoming ethnic cleansing of supposed Haitians from the Dominican Republic

Haiti has been mentioned here at Demography Matters a few times. In January 2010 after the devastating earthquake, for instance, I described the evolution and prospects of the substantial Haitian diaspora and also explained why a quixotic offer by the Senegalese president to resettle Haitians in Africa was not likely to lead anywhere, June 2010 mentioning that French-using Haiti was major source of immigrants to Québec and then in December 2011 noting how a migration of Haitian professionals to post-colonial Congo in the 1960s seems to have been the key movement that introduced HIV/AIDS to the Atlantic world. The Dominican Republic has come up more rarely, in 2006 and in 2009 being mentioned as a Caribbean Hispanophone society that has consistently seen more rapid population growth than once-dominant Cuba. As far as I can tell, the long and entangled history that has led, via migration from low-income Haiti to the middle-income Dominican Republic, to a population of Haitian origin in the latter country amounting well over a million people has never come up here.

It's coming up now. As The Guardian's Sibylla Brodzinsky reports, a new citizenship law is set to strip hundreds of thousands of these people of their citizenship in Dominican Republic, rendering them liable to deportation from the land of their birth and statelessness.

[Yesenia Originé] was born in the Dominican city of San Pedro de Macorís to Haitian parents. But because she has no papers to prove it, she, like thousands of other people of Haitian descent in the Dominican Republic, risks being rounded up and deported to the neighboring country.

Many people in Originé’s situation are fearing the worst ahead of the Wednesday deadline for an estimated 500,000 undocumented persons living in the Dominican Republic to register with government authorities. The country’s authorities have reportedly lined up a fleet of buses and established processing centers on the border with Haiti, prompting widespread fears of mass roundups of Dominicans of Haitian descent.

“If they send me there, I don’t know what I’ll do,” says 22-year-old Originé who lives in a batey – a company town for sugarcane workers – in the south-west of the Dominican Republic.

A 2013 court ruling stripped children of Haitian migrants their citizenship retroactively to 1930, leaving tens of thousands of Dominican-born people of Haitian descent stateless. International outrage over the ruling led the Dominican government to pass a law last year that allows people born to undocumented foreign parents, whose birth was never registered in the Dominican Republic, to request residency permits as foreigners. After two years they can apply for naturalisation.

However many have actively resisted registering as foreigners because they say they are Dominican by birth and deserve all the rights that come with it – for example a naturalised citizen cannot run for high office.

Abby Philipp at the Washington Post went into more detail about the racism motivating this denationalization. Following the once Spanish Dominican Republic's separation from formerly French Haiti, the young republic set out to define its national identity in direct contrast to that of its neighbour. This meant, among other things, strong anti-black and anti-Haitian racism that culminated at least in the 20th century in an act of genocide.

There was a time when that split between the two countries was drawn with blood; the 1937 Parsley Massacre is widely regarded as a turning point in Haitian-Dominican relations. The slaughter, carried out by Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo, targeted Haitians along with Dominicans who looked dark enough to be Haitian -- or whose inability to roll the "r" in perejil, the Spanish word for parsley, gave them away.

The Dajabón River, which serves as the northernmost part of the international border between the two countries, had "risen to new heights on blood alone," wrote Haitian American author Edwidge Danticat.

"The massacre cemented Haitians into a long-term subversive outsider incompatible with what it means to be Dominicans," according to Border of Lights, an organization that commemorated the 75th anniversary of the massacre in 2012.

[. . .]

Cassandre Theano, a legal officer at the New York-based Open Society Foundations, said the comparisons between the Dominican government's actions and the denationalization of Jews in Nazi Germany are justified.

"We've called it as such because there are definitely linkages," she told The Washington Post this week. "You don't want to look a few years back and say, 'This is what was happening and I didn't call it.' "

Julia Harrington Ready, also of the Open Society Foundations, is right to call this ethnic cleansing.

The potential consequences of this for the two nations of Hispaniola, and for the wider region, cannot be understated. Even if this population at risk of mass deportation actually was Haitian, even five years after the earthquake Haiti is in no position to handle hundreds of thousands of deportees. For the Dominican Republic, meanwhile, I would be willing to bet that whatever nationalists might think they would gain in terms of a homeland rid of these people will be outweighed by the actual losses experienced. (Getting rid of large chunks of your workforce generally does not do good things for the economy.) Meanwhile, this ethnic cleansing will be certain to produce substantial numbers of people who will likely need resettlement outside of these region, just like other ethnic cleansings in the recent past.

This is not good. This is really not good at all. Be alarmed, readers. Maybe we can do something to prevent this catastrophe.

Saturday, October 18, 2014

Some thematic links: France, Ukraine, Russia, Japan, China, South Pacific

I've been collecting links for the past while, part of my ongoing research into some interesting topics. I thought I'd share some with you tonight.

Tuesday, April 23, 2013

Some notes on the Chechens and Chechen demography

Last Monday's Boston Marathon bombings gave some most unattractive publicity to the Russian autonomous republic of Chechnya and the Chechen people, on account of the ethnicity of the alleged perpetrators, Dzhokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev. One thing that came out in their life stories was they way in which they recapitulated the 20th century demographic history of the Chechens, able summarized in Asya Pereltsvaig's Geocurrents post.

During World War II, some Chechen separatists saw an opportunity to escape Russian domination by siding with the fast-approaching Nazis, who pushed into the North Caucasus in November 1942, attracted by the rich oil fields near Baku (see map on the left). Under that slight pretext, Stalin ordered virtually the entire Chechen population to be herded up and shipped by train to Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Siberia on February 23, 1944. Up to 40% of the Chechen nation perished in the process, according to Stanford historian Norman M. Naimark. Houses of the exiled Chechens were offered to refugees from the war-ravaged western regions of USSR. But Stalin sought not only to move the Chechens away from the area of potential German conquest, but to destroy their ethnic identity. Chechen gravestones and cultural monuments were demolished; whole villages were deleted from maps and encyclopedias. In 1956, during Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization program, those Chechens who had not perished during their harsh 13-year exile were “rehabilitated” and permitted to return back to their homeland. Nonetheless, the survivors of the exile lost economic resources and civil rights. They have also continued to suffer from discrimination, both official and unofficial, and have endured years of discriminatory public discourse.

[. . .]

In the ensuing First Chechen War, the Russian air force and artillery hammered Chechen cities, particularly the capital of Grozny, which is now considered “the most destroyed city in the world”. Hundreds of thousands of Chechen refugees were driven out of Chechnya and into other parts of the Caucasus, particularly Ingushetia and Dagestan (where the younger of the Boston bombers, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, attended school). Others went further afield, to the United States, Europe, or Central Asia, where Chechen communities remained since the exile ordered by Stalin. In the meantime, rebel forces in Chechnya retreated to the mountains, resorting to guerrilla warfare and terrorist attacks. Using tactics similar to those developed by the mujahideen in Afghanistan, rebels wore down the Russian troops; alcohol, drugs, and terror also took a heavy toll on the Russian military enterprise. Russian forces responded by fighting not only the armed rebels but also by inflicting destruction and rape on the peaceful Chechen population. As Russian casualties mounted, public opinion turned against the war. Russia agreed to a ceasefire in 1995, but since the political issues underlying the conflict were not resolved, violence soon resumed. After Dudayev was killed by two laser-guided missiles fired by a Russian aircraft, a new ceasefire agreement was brokered in 1996, calling for withdrawal of Russian forces and a political resolution in 2001.

[. . .]

Initially, the Second Chechen War went better for Moscow than did the First Chechen War. Russia launched massive and indiscriminate air strikes, forcing as many as 400,000 Chechens to flee. However, Moscow quickly became trapped again in an Afghan-style quagmire, while international condemnation mounted. Chechen president Maskhadov made several abortive attempts to cut a deal with the Russians, but found himself dismissed by Moscow and increasingly ignored by his own compatriots. He fled Grozny in 1999, as violence continued to escalate on both sides (eventually, Maskhadov was killed by Russian special forces in March 2005). He was replaced by a Chechen cleric Akhmad Kadyrov, who broke with the anti-Russian resistance movement, in part over its increasing religious radicalism, and began working with Russian authorities. After prolonged and bitter resistance, the Russians finally recaptured Grozny in early 2000, though the insurgency phase continued throughout the 2000s.

Born in a family of mixed ethnicity (Chechen father, Avar mother) in the eastern North Caucasus, moving at an earlier age to Kyrgyzstan an eventually to the United States, maintaining close connections to their homeland, the Tsarnaev brothers represent extremes in many ways. For starters, very few ethnic Chechens live in the United States--the number is approximately two hundred or so. (Most of the Chechens in the United States do live in the Boston area.) The Chechen diaspora, large and growing after the past century of genocides and wars, is concentrated in Eurasia: in Central Asia, particularly Kazakhstan but also Kyrgyzstan, where Chechens were deported in the Second World War and where substantial Chechen communities remain; in the remainder of the Russian Federation, where Chechens have travelled in major cities in the hope for a better life; in Turkey, where substantial Chechen migration dates to the 19th century expulsions of Muslims from the Russian North Caucasus; and, in western Europe. More notably, the Tsarnaev brothers stand out among the Chechen diaspora as the first Chechens to commit a terrorist act outside of Russia, the 1996 hijacking of a Russia-Turkey feerry aside. Olivier Roy (at The New Republic) and Anne Applebaum (at Slate) are probably right to classify the Tsarnaev brothers' alleged bombing as product of the alienation of first-generation immigrant children from their adopted homeland, not some sort of transnational network.

(I made two links posts on the subject Saturday, one of links to interesting blog posts and one of noteworthy news articles.)

Chechnya does stand out in the Russian Federation for any number of factors, of which--as described by Saidova and Zemlyanova the still-high Chechen fertility rate is a notable factor. Despite the terrible casualties of a decade of war, estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands, Chechnya has one of the highest fertility rates of any unit in the former Soviet Union.

In the last few years after the socioeconomic situation stabilized and population of the Chechen republic returned to peaceful life favorable development trends of demographic situation are being formed with positive factors of natural increase of population and increase in population number.

From the moment when collection of official demographic statistics was resumed in the republic in 2003 the following population dynamics is traced: as to January, 1 in 2004 number of population was 1121 thousands, and by January, 1 in 2009 it increased up to 9.5% and was 1238 thousands. Total fertility rate (TFR) in Chechen republic exceeds the replacement level. In 2008 it was 3.40 per woman at the age of 15- 49. For comparison, in the same year TFR in neighboring Republic of Dagestan was 1.95, in Republic of Ingushetia it was 1.96, in the whole South Federal District it was 1.67 and in the whole Russian Federation it was 1.49.

This does fit into a general trend, outlined by Judyth Twigg's December 2005 analysis, of Muslims in the Russian Federation evidencing higher fertility rates than non-Muslims. However, Valery Dzutsev's November 2010 Eurasia Daily Monitor analysis makes the point that there are good reasons to doubt the validity of the census data, particularly in the context of extremes.

Many experts have expressed doubts about sudden population increases in the North Caucasian republics over the past 10 years. For instance, Ingushetia’s population officially increased from just under 190,000 in 1990 to a whopping more than 455,000 in 2002 and 516,000 in 2010. Chechnya’s population, following two devastating wars that displaced hundreds of thousands people and virtually eliminated the large ethnic Russian minority in the republic, also increased from 1.1 million in the 1990 to an estimated nearly 1.3 million in 2010, according to the official statistics (www.gks.ru, accessed on November 14).

[. . .]

The demographics of Chechnya are a politically sensitive topic, as the population of the republic was significantly reduced by the two wars and the accompanying destruction of its cities and villages in the 1990’s and again in the 2000’s. Because Ingushetia and Chechnya formed a single administrative entity until the disbandment of the USSR, Ingushetia’s population also had to be manipulated to cover up the real losses among the locals.

The prominent North Ossetian sociologist Aleksandr Dzadziev estimated that Chechnya lost at least 455,000 of its prewar population from 1989-2002, as a result of both migration and casualties. Just before the 2002 census, estimates of Chechnya’s population varied significantly, from 650,000 by the Russian statistical committee to 850,000 by the pro-Moscow Chechen government and Dzadziev’s own estimate of 820,000, all of them much lower than the officially announced results of the 2002 census –1.1 million people (http://www.kavkaz-uzel.ru/analyticstext/analytics/id/765541.html).

It is understandable why both Moscow and its puppet regime in Grozny were interested in exaggerating the population numbers for Chechnya in 2002. Moscow wanted to show there were not too many casualties and that the refugees had returned to Chechnya, while the local authorities wanted to receive more funds and thus needed a higher population to justify their demands. However, it is less clear as to why other North Caucasian republics overstated their populations in the 2002 census. Dagestan’s official population was put at 2.6 million, while according to the year-to-year estimates of the Russian statistical service and Dzadziev’s own estimates it should have been only about 2.2 million. The expected population of Ingushetia in 2002 was 430,000, but came out as 469,000. The expected population figure for Kabardino-Balkaria was about 780,000, but it jumped to over 900,000.

The official explanation for the rapidly increasing populations of the North Caucasian republics is that they have higher birthrates. This is especially applicable to Dagestan, Chechnya and Ingushetia. Still, it is doubtful that the people of Chechnya possess the highest fertility rate in Russia –one that is at the same level or exceeds Saudi Arabia’s and Iraq’s fertility rates.

Migration from Chechnya has occurred on a large scale owing to reasons of war and political oppression, but out-migration is a major theme of the North Caucasian Federal District generally, the only one of Russia's eight federal districts to have a non-Russian majority. (Two-thirds of the North Caucasian Federal District's population is non-Russian, a proportion that would rise if the largely Slavic Stavropol Krai was excluded.) The North Caucasus is a poor region, but young, and Russian government plans for the economic development of the North Caucasus seek to encourage migration to regions elsewhere in Russia.

Demographics of the North Caucasus Federal District differ from that of Russia in general. Now the demographic situation in the region is stable to the increase of birth and decrease of death rate, as well as mass migration to the region. The population of the region increased from 1990 to 2009 by 1.68 million people and is now 13.437 million people. In the year 2009 the natural increase of the population in the North Caucasus Federal District was 75.6 thousand people.

[. . . ]

The birth rate in the North Caucasus Federal District is the highest in the Russian Federation. Especially high is the birth rate in Chechnya (29 new-born children per 1000 residents) and Dagestan (19 new-born children per 1000 residents). That is why the percentage of the young people in the North Caucasus Federal District is higher than in other regions of the Federation. Especially high is the percentage of the youth in such subjects of the Federation as Chechnya (32.9%), Ingushetia (28.9%), and Dagestan (25.4%).

[. . . ]

The level of urbanization is rather low due to the traditional agricultural specialization of the region. The percentage of rural population in 2009 was 51.2%, in 2010 51.1% (in Russia this number is 26.9), that means that 4729.1 thousand people live in rural area. In the Republic of Dagestan, in the Republic of Ingushetia, and in the Republic of Karachay-Cherkessia the percentage of the rural population is 56 – 57%. In the Chechen Republic the figure is 64.7 percent. The infrastructure in the rural areas is rather poor and that prevents labour migration and determines low quality of life of the local residents.

The forces migration is another acute problem. Various ethnic and international conflicts force people to migrate to other regions of the Federation. In 2008 population loss due to migration formed 11.9 thousand people. In Dagestan this figure was 9.8 thousand people, in Kabardino-Balkaria 2.9 thousand, in North Ossetia 2.7 thousand, in Karachay-Cherkessia 1.9 thousand, and in the Chechen Republic 1 thousand people. Population increase due to migration was registered in Stavropol Territory.

The problem of migration is to be solved by the Federal Center together with local authorities. This will require a series of political, social, economic and cultural measures. The average annual labour migration from the region to the other regions of Russia should be on the level of 30 – 40 thousand people. This will stabilize the demographic situation in the region and lower unemployment level.

One third of the population of the North Caucasus Federal District is young people. This means that the Government should adopt a sufficient youth policy. Such a policy should focus on the development of youth organizations, trade union and labour market. The Federal Government together with local authorities should support young entrepreneurs and young families, support education and healthcare system, popularize sports and national traditions of the Caucasian people, and tolerance.

The Danish Immigration Service's 2011 report on Chechens in Russia outlines the various pressures on Chechens to migrate from their homeland, and the legal and other problems that they encounter elsewhere in the Russian Federation. Anti-Chechen discrimination and violence, often state-sponsored, is quite common. All this occurs in the context of what is described, in the 2007 paper of Vendina et al, as the "demographic diversification of the North Caucasus, as Russian and other Slavic populations decrease in number while the largely Muslim populations of nationalities indigenous to the North Caucasus grow.

Labels:

chechnya,

demographics,

diasporas,

eastern+europe,

ethnicity,

history,

russia

Tuesday, March 19, 2013

On multicultural Cyprus

The latest stage of the ongoing Cypriot financial crisis, a haircut imposed on depositors in Cypriot banks, has been covered very extensively throughout the blogosphere and the wider news media. We can only be thankful, I suppose, that there hasn't been a general run on banks across southern Europe. (Pessimists would remind me, correctly, that there is still time.)

One thing that has come up in the coverage is the extensive international involvement in the Cypriot crisis: Cypriot banks loaned to Greece and exposed themselves heavily, British expatriates and Russian investors have complained about their losses, and so forth. It's a minor irony that Cyprus, a small island with a total population of a million people, has become so globalized. Its strategic location can be thanked for that--in 1878, as the Ottoman Empire trembled in the aftermath of the catastrophic war over Bulgaria I blogged about earlier this month, Britain took Cyprus on as a protectorate, counting on using its strategic location to help protect the Suez Canal. Evolving after the start of the First World War into a fully-fledged crown colony, old Ottoman traditions of quiet co-existence between two ethnic groups began to evolve into the seeds of ethnonational conflict.

The Ottomans tended to administer their multicultural empire with the help of their subject millets, or religious communities. The tolerance of the millet system permitted the Greek Cypriot community to survive, administered for Constantinople by the Archbishop of the Church of Cyprus, who became the community's head, or ethnarch.

[. . .]

In the light of intercommunal conflict since the mid-1950s, it is surprising that Cypriot Muslims and Christians generally lived harmoniously. Some Christian villages converted to Islam. In many places, Turks settled next to Greeks. The island evolved into a demographic mosaic of Greek and Turkish villages, as well as many mixed communities. The extent of this symbiosis could be seen in the two groups' participation in commercial and religious fairs, pilgrimages to each other's shrines, and the occurrence, albeit rare, of intermarriage despite Islamic and Greek laws to the contrary. There was also the extreme case of the linobambakoi (linen-cottons), villagers who practiced the rites of both religions and had a Christian as well as a Muslim name. In the minds of some, such religious syncretism indicates that religion was not a source of conflict in traditional Cypriot society.

The rise of Greek nationalism in the 1820s and 1830s affected Greek Cypriots, but for the rest of the century these sentiments were limited to the educated. The concept of enosis--unification with the Greek motherland, by then an independent country after freeing itself from Ottoman rule--became important to literate Greek Cypriots. A movement for the realization of enosis gradually formed, in which the Church of Cyprus had a dominant role.

What's more, after the conclusion of the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922 led to a near-complete separation of Greeks and Turks into their respective nation-states, Cyprus was the only remaining substantial territory where Greeks and Turks lived mixed. It may have been inevitable that after independence, conflict between the Greeks and the Turks would eventually escalate into full-fledged war, resulting in a 1974 Turkish military intervention that led to the creation of a Turkish North Cyprus separate from the internationally-recognized--and overwhelmingly Greek--Republic of Cyprus.

As noted in the Library of Congress study on the country, published in 1991, Cyprus--like many other island societies--saw substantial emigration in the post-Second World War period, directed towards the colonial metropole of the United Kingdom.

The periods of greatest emigration were 1955-59, the 1960s, and 1974-79, times of political instability and socioeconomic insecurity when future prospects appeared bleak and unpromising. Between 1955 and 1959, the period of anticolonial struggle, 29,000 Cypriots, 5 percent of the population, left the island. In the 1960s, there were periods of economic recession and intercommunal strife, and net emigration has been estimated at about 50,000, or 8.5 percent of the island's 1970 population. Most of these emigrants were young males from rural areas and usually unemployed. Some five percent were factory workers and only 5 percent were university graduates. Britain headed the list of destinations, taking more than 75 percent of the emigrants in 1953-73; another 8 to 10 percent went to Australia, and about 5 percent to North America.

During the early 1970s, economic development, social progress, and relative political stability contributed to a slackening of emigration. At the same time, there was immigration, so that the net immigration was 3,200 in 1970-73. This trend ended with the 1974 invasion. During the 1974-79 period, 51,500 persons left as emigrants, and another 15,000 became temporary workers abroad. The new wave of emigrants had Australia as the most common destination (35 percent), followed by North America, Greece, and Britain. Many professionals and technical workers emigrated, and for the first time more women than men left. By the early 1980s, the government had rebuilt the economy, and the 30 percent unemployment rate of 1974 was replaced by a labor shortage. As a result, only about 2,000 Cypriots emigrated during the years 1980-86, while 2,850 returned to the island.

Although emigration slowed to a trickle during the 1980s, so many Cypriots had left the island in preceding decades that in the late 1980s an estimated 300,000 Cypriots (a number equivalent to 60 percent of the population of the Republic of Cyprus) resided in seven foreign countries.

Now, however, Cyprus has become a major destination for immigration. The politically most critical immigration has been in North Cyprus, where migration from Turkey--permanent and otherwise--has occurred on a politically controversial scale. Some estimates suggest that half of the population of North Cyprus, numbering something on the order of a quarter-million people, is of first- or second-generation Turkish immigrant background. This alleged high proportion was one reason why Greek Cypriots rejected the 2004 Annan plan for reunification of the island: a North that was substantially or maybe even mostly populated by immigrants wasn't a legitimate negotiating partner. Turning to the Norwegian International Peace Research Institute (PIRO), however, Mete Hatay's 2007 report "Is the Turkish Cypriot Population Shrinking?" makes a compelling case that this proportion is a large overestimate, product of authentic measurement errors and judgements of bad faith all around. I don't feel qualified to make any judgement on these figures apart from observing that a neutral third-party could be very useful.

Less politically controversial has been the substantial immigration into the Republic of Cyprus, amounting to a quarter of the total population of the European Union member-state. Attracted by the island-state's pleasant climate and (until recently) dynamic economy, tens of thousands of people have immigrated to Cyprus, from distant Britain (stereotypically retirees and other expatriates), from Balkan countries like Bulgaria, Romania and Greece, and from Russia. I've been following Russian interest in Cyprus for a bit at my blog. Suffice it to say that Cyprus' status as an offshore financial centre for Russians, its pleasant environment, and sentimental bonds of Orthodox Christianity shared with Russia helped make Cyprus a destination on par with Montenegro in the Balkans and Latvia. (Apparently the European Union is now in the process of making sure that the financial system of Latvia, slated to accede to the Euro next year, is free from Cypriot excesses.) Early in February, a Guardian report claimed that the Chinese were starting to come to Cyprus.

It will soon be carnival time in the city of Pafos on the south-west coast of Cyprus – and this year theme is China.

"Everything will be Chinese," says Pafos mayor, Savvas Vergas, in his office in the pretty, whitewashed city hall, fronted by classical Greek pillars. "Meals … folklore … Everything will be on Chinese culture."

The carnival will be a way of celebrating a most unusual boom in a country which, like others in southern Europe, has been stricken by the eurozone crisis. Property prices in Cyprus have fallen by around 15% since 2007. Yet an official survey published last month found that between last August and October more than 600 properties were sold to Chinese buyers, 90% of which were in Pafos.

"The real growth came after August because that was when the government made clear the terms and conditions for third country nationals to get permanent residence," says Giorgios Leptos, a director of the Leptos property group and president of the Pafos chamber of commerce and industry.

The opportunity to secure permanent residence in an EU member state is a huge attraction for Chinese because it offers them visa-free travel throughout the union. Almost 4,500 miles away, Lisha Tang, a young client at a Beijing property firm, is relishing the prospect.

"A house in Cyprus means travelling freely in Europe, which is great for young people," she says.

[. . .]

To obtain permanent residence in Cyprus, investors from outside the EU have to spend at least €300,000 (£260,000) on a property. They must also prove that they have no criminal record and are in good financial standing and agree to deposit €30,000 for a minimum of three years in a local bank account. Their permit normally arrives in about 45 days.

Cyprus is not the only EU state to be exploring this way of reinvigorating a stagnant property market. Last year, Ireland and Portugal also offered residency to foreigners who bought property worth more than a certain amount. In November Spain's trade minister, Jaime Garcia-Legaz, said his country was intending to follow suit in an attempt to clear his country's vast backlog of unsold homes.

Some of Cyprus' super-rich immigrants will fall prey to the bank levy.

A band of super-rich foreign tycoons who took Cypriot citizenship in recent decades – lured by a favourable tax regime – are expected to be among the hardest hit by the island's surprise deposit tax as several are believed to have been required to deposit at least €17m of their fortunes on the island to qualify for citizenship.

Billionaires attracted to the island by the controversial citizenship scheme, designed to court super-rich figures, include Norwegian-born oil tanker tycoon John Fredriksen, Israeli internet gambling entrepreneur Teddy Sagi, and Alexander Abramov, the Russian steel magnate who chairs FTSE 100 group Evraz.

Cyprus's then interior minister, Neoclis Sylikiotis, explained the rules to local newspaper Cyprus Weekly in 2010: "Cypriot nationality is given in special cases, following approval from the council of ministers … on the basis of specific criteria, including the applicant being over 30, having no criminal record, owning a permanent home in Cyprus and travelling to the island."

Further criteria include depositing at least €17m with a local bank over five years, direct investments of €30m, or registering a large business on the island.

Between 2007 and 2010 some 30 foreign nationals, mostly Russians, were reportedly granted Cypriot citizenship. Most prominent among them was Abramov. "Mr Abramov is considered to be offering high level services to the Republic of Cyprus, taking into account his business activities," explained Sylikiotis. "Therefore, reasons of public interest justify his naturalisation as a special case."

Whether or not any of this immigration will survive in the aftermath of the bank levy is open to question. In the case of Russia, initial outrage seems ready to lead to disengagement for stabler economic climes. A resurgence of Cypriot emigration, perhaps from both halves of the island, can't necessarily be excluded. I wonder what contingency plans the United Kingdom might have.

Friday, March 01, 2013

Three notes on historical patterns of migration from Bulgaria

Edward Hugh's essay earlier this week at A Fistful of Euros, "The Shortage of Bulgarians Inside Bulgaria", got a non-trivial amount of attention, including linkage by Marginal Revolution's Tyler Cowen. (See also Economonitor which mirrors the post though not the comments, and, of course, here at Demography Matters.) Within the European Union, Bulgaria really does constitute an exceptional case: among the poorest European Union member-states, with one of the lowest fertility rates of any European Union member-state, and with some of the highest rates of emigration, Bulgaria is quite likely because of its rapidly shrinking population to experience the serious economic and other problems other countries are likely to experience in the near future. The country's population has fallen by a sixth from its peak in 1985, in fact.

Bulgaria has lost 582,000 people over the last ten years, a nationwide census has revealed. The EU newcomer, who has now 7,351,633 inhabitants, has lost 1.5 million of its population since 1985, a record in depopulation not just for the EU, but by global standards too.

Bulgaria, which had a population of almost nine million in 1985, now has almost the same number of inhabitants as in 1945 after World war II, the Bulgarian media writes.

The census also found that the Bulgarian population is ageing fast, that the number of young people is declining and that villages are becoming depopulated as big cities grow.

People of more than 65 years of age in 2001 constituted 16.8% of the population, while this year their rate has grown to 18.9%. At the same time, the number of children has declined, which is a clear sign that ever fewer employed people will have to provide for a growing number of elderly people[.]

Bulgaria of some interest to me in that it's a new country, in many respects newer than my Canada. Yes, Bulgarians have lived in Bulgaria for centuries without any experience of historical discontinuity as severe as that experienced by Canada, which has been almost completely repopulated by Old World migrants. Still, the Bulgarian state is a young entity: the Principality of Bulgaria was established by the Great Powers in 1878; Bulgaria was unified with adjacent and autonomous Eastern Rumelia in 1885; Bulgaria declared its independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1908; Bulgaria's current borders were only definitively settled in 1946 as the Cold War began. As much as Bulgaria is a modern European nation-state now, its history--including its migration history--bears the marks of its recent past.

1. Let's start with the migration patterns of Bulgaria's Turks and Muslims.

Taken from here, this chart shows basic census results by ethnicity between 1880 and 1910 in Bulgaria. Noteworthy is the near-doubling of the Bulgarian population over this timeframe while the Turkish population falls by a third. The Turkish population of Bulgaria may have fallen further, in fact: one estimate in the Wikipedia article on Turks in Bulgaria claims that in the Danube Vilayet, which occupied most of northern Bulgaria along with parts of what are now coastal Romania, Christians of all ethnicities formed barely half of a population of almost 2.4 million people. The high proportion of Muslims in mid-19th century Bulgaria makes sense if you think of Bulgaria not as a peripheral European nation, but as a collection of provinces which formed part of the core of the Ottoman Empire, in the hinterland of the capital, even.

Muslims in Bulgaria, like Muslims elsewhere in the independent states emerging from the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans, and in the lands conquered by the Russian Empire in the Caucasus, were generally unwelcome presences in these newly Christian lands. As detailed by--for instance--Berna Pekesen in the essay "Expulsion and Emigration of the Muslims from the Balkans", Muslims of all backgrounds--people of indigenous Balkan background like Slavs and Albanians, members of Turkic groups, and peoples of the Caucasus like the Circassians--were subjected to what would be called ethnic cleansing. Millions of muhajir ended up settling in the Turkish core of the Ottoman Empire, starting off that country's modern tradition of immigration. (Various estimates claim that a high proportion of Turks, some up to one-third, are descended from these refugees.) In Bulgaria's case, Pomaks--people of Bulgarian language but Muslim religion--were separated from the Turkish population by various governments, which hoped to assimilate the Pomaks into a Bulgarian ethnic identity.

Bulgaria kept a larger Turkish and Muslim population that many other Balkan countries, but towards the end of the Communist period a variety of violent policies mandating the assimilation of all Muslims, including forced renamings and closing down specifically Muslim facilities, culminating in the May 1989 expulsion of most Bulgarian Turks from their country of birth into adjacent Turkey. The terrible international reaction and the economic consequences of the mass expulsion helped bring down the Communist government and fairly quick restitution made to the Turks (and Pomaks) as part of the democratization process. Today, Turks and Muslims in Bulgaria seem--some concerns aside--to be well-integrated in their homeland as respected players, with their political party, the Movement for Rights and Freedoms, being a major political player. Even so, perhaps a third of the million people claiming an identity as Bulgarian Turks currently live in Turkey, a country where they have put down roots. The Bulgarian emigrant community in Turkey, in fact, is the largest community of Bulgarian emigrants, the half-million Bulgarians in Turkey outnumbering registered Bulgarian emigrants in the rest of the European Union combined.

2. Bulgaria's borders are not what many had hoped.

Initially in 1878 Bulgaria under Russian sponsorship would have been a large country indeed, including within its borders not only modern Bulgaria but almost all of the historical region of Macedonia. The negative reaction of other powers to such a large Bulgaria, seen as a Russian pawn threatening Constantinople and the Straits, led to the creation of a smaller Bulgaria. Despite fighting numerous wars at great cost with the aim of gaining these territories, Bulgaria never did manage to gain more than a small piece of Macedonia. After multiple ethnic cleansings all around which saw the deportal of most of the region's Muslims to Turkey and the eventual expulsion and forced assimilation of most Slavs in an Aegean Macedonia that received many of the Greeks expelled from Turkey in 1922, and the creation in Tito's Yugoslavia of a Macedonian national identity separate from the Bulgarian, Bulgaria was left with only a portion of eastern Macedonia. As for Bulgarian communities scattered further afield, whether in neighbouring Balkan countries or in old immigrant communities on the northern shore of the Black Sea (Moldova, Ukraine, Russia), they were left out of the Bulgarian national project.

After 1989 and the collapse of Yugoslavia, Bulgarian citizenship laws were slowly transformed so as to give people claiming an identity as ethnic Bulgarians, including those living in countries immediately adjoining Bulgaria as well as those living in the Black Sea diaspora. This was merely the most prominent part of a policy of outreach to these diasporids that includes gifts of school books in Serbia or vice-presidential visits in Ukraine. As noted by Marko Žilović in an essay at the website Citizenship in Southeastern Europe, citizenship in Bulgaria--a country on track to join the European Union, no less--could be a potent economic advantage.

On a usual working day in the village of Ivanovo in Serbia there are three cars with Bulgarian license plates parked in front of the small elementary school. This is not because a delegation from Bulgaria is visiting this village of little more than 1000 inhabitants. Importing used cars licensed in Bulgaria was a well-known scheme to circumvent restrictive Serbian regulations that protect the Zastava company, the only domestic car producer. The scheme worked best if the buyer had a Bulgarian passport. It is thus no coincidence that several cars with Bulgarian license plates found their way into the Ivanovo, for it is one of the few places where fleeing Roman Catholic Slavs from northern Bulgaria settled in the 18th century. Today, about a fifth of Ivanovo’s population declare themselves ethnic Bulgarians, though probably only a handful of them have obtained Bulgarian passports. However, among the owners of the Bulgarian-licensed cars, and passports, is also a local math teacher who declares himself an ethnic Serb. He tells of having some ethnic Romanians in his family tree a few generations ago, but no Bulgarian connections whatsoever.

By far the biggest number of people claiming Bulgarian ethnic identity to get Bulgarian citizenship are from Macedonia. While Bulgaria recognizes Macedonian independence, it does not recognize the separate existence of a Macedonian nationality, leaving open the possibility for Macedonian Slavs--of which there are 1.2 million in the former Yugoslav republic--to declare themselves Bulgarians. Given Macedonia's likely continued exclusion from the European Union owing to the name dispute with Greece and an emergent history dispute with Bulgaria, claiming a Bulgarian ethnic identity makes sense. Joanne van Selm's June 2007 profile of Macedona notes this.

It goes without saying that this is exceptionally controversial in Macedonia.

The Bulgarian case is fairly represented in Milena Hristova's February 2010 article for the Sofia News Agency, "Bulgarian Passports for Macedonians: Debunking Myths".

Macedonians strive to obtain Bulgarian citizenship for a number of reasons – to migrate to Bulgaria, to travel and work freely across the European Union and also due to the faith in the protection that the Bulgarian state can give them. “I would risk saying that this emotional factor is the most important and most often cited reason,” says Mandzhukova. She vehemently denies that the real motives are more pragmatic. “To say that Macedonians obtain Bulgarian citizenship as a passport to Europe is a stereotype that gives a very distorted reflection of the truth,” she says. According to her the influx of Macedonians to Bulgaria did not increase significantly after the country's accession to the European Union on January 1, 2007. “The first signs f the hype came much earlier when Bulgarian institutions agreed that the document our agency issues is enough to claim Bulgarian origin. This is when the real increase in applications came due to the streamlining of the process.” While in Macedonia many Macedonians try to cover the fact that they have signed such a declaration. “Well, certainly nobody will shout it at the top of his lungs. But first of all if someone considers what the Macedonian authorities think important, he would not sign the declaration in the first place, “ Mandzhukova says.

(A April 2012 essay by the Sofia News Agency argues the Bulgaria gives Bulgarian nationality to many fewer Macedonians than Romania gives Romanian nationality to many fewer Moldovans, and is more moderate.)

The Macedonian International News Agency, meanwhile, doesn't address directly the denial of Macedonian nationhood, instead challenging via articles like "Bulgarian citizen: Should my wife become Macedonian to get Bulgarian Passport?" (published earlier this month) the justice of a citizenship policy that makes it difficult for long-time residents to naturalize.

"Practically none of the Macedonans who have obtained a Bulgarian passport lives in Bulgaria. A large majority of them obtain the passport so they can work in EU countries. My wife on the other hand lives in Bulgaria for 11 years, speaks perfect Bulgarian, pays taxes, however is unable to obtain a citizenship" explains Bulgarian citizen Stefan Rusenov in an interview with Dnevnik.

In Bulgaria, you need to be a Macedonian so you can obtain a Bulgarian citizenship or passport overnight.

Macedonians in Bulgaria don't speak Bulgarian, they don't pay taxes here, but when it comes to obtaining our citizenship, they do it in record time, within a year - says Stefan Rusenov whose wife is from the Ukraine and is unable to obtain Bulgarian citizenship for years. According to Bulgarian laws, she would need to give up her Ukrainian passport to become citizen of Bulgaria.

- Instead of receiving a response in a year, we got our response in three years - that my wife can obtain a citizenship in three years, but, the condition was she must give up her Ukrainian citizenship. Then more problems. From the Ukrainian Embassy we were told she must register to fulfill her request of giving up her Ukrainian citizenship (which lasts 8 months), and only after that she can submit her request to give up her Ukrainian passport - explains Rusenov in frustrating fashion.

3. Bulgaria has long been a European periphery.

There is an abundant literature about migration from post-Communist Bulgaria, for instance the Open Society Bulgaria 2005 report "Bulgarian Migration: Incentives and Constellations", a 2013 fact sheet from the same organization "Is There A Threat of Bulgarian Migration to the UK?" (quick answer: no), Fatma Usheva's 2011 thesis "Emigration from Bulgaria: 1989 - Today", or Eugenia Markova's 2010 report for the Hellenic Observatory, "Effects of Migration on Sending Countries: Lessons from Bulgaria". Suffice it to say that after the end of the Soviet Union, Bulgarian migrants went first to adjacent and relatively prosperous Greece, then starting to move in large numbers to Spain in the late 1990s, with Germany recently emerging as a destination of choice. Bulgarian migrants went to places where they could find jobs easily, often in the informal sector, usually in countries that were relatively close to their homeland. Bulgarian foreign minister Nikolay Mladenov was quite right to tell The Telegraph that Bulgarians are not especially likely to move to the United Kingdom in large numbers.

These three patterns of migration, driven by ethnic identity and relative underdevelopment, seem likely to endure. The odds of Bulgaria transforming sufficiently to not be a relatively poor country with low fertility and very high rates of emigration are not, as Edward noted, high at all. Individual Bulgarians have every incentive to continue to leave their country, and with Bulgaria's full integration into the European Union's single market in labour, very few institutional barriers. It's also fair to wonder whether Turkey, just next door with relatively strong economic growth and a recent history of receiving large numbers of Bulgarian migrants, might also emerge as a destination for Bulgarians regardless of whether Turkey joins the European Union or not. Inasmuch as Macedonia, and the adjacent countries with large Bulgarian communities (Serbia, Moldova, Ukraine)

Labels:

bulgaria,

eastern europe,

economics,

ethnicity,

european union,

fertility,

migration,

turkey

Saturday, February 23, 2013

On North Korea becoming a place where people are from

Writing at Lawyers, Guns, and Money, Robert Farley linked to some interesting efforts being made to plan for Korean reunification. Reacting to this conference report, one Robert Kelly took issue with the idea that reunification could be managed as anything but a wholesale and terrible expensive takeover of the North by the South, on account of the North Korean state's lack of legitimacy compared to South Korea.

This will bring about numerous issues, especially he notes in regards to migration issues.

Getting NK up to speed ASAP is also necessary to forestall a massive migration southward with consequent North Korean ghettoes emerging around Southern cities and all the crime, resentment, and pseudo-identity politics that would create. The likely food shortages alone will probably drive Northerners southward. USFK/ROKA ideas of air-dropping food into North Korea are band-aids, and notions of a green revolution to improve NK agricultural production will take several years to fall into place. But the obvious attraction of Southern lifestyles will be the true driver as it was in Germany, a point I am surprised was not made in the report.

It is worth noting how much internal migration there was in unified Germany. Pusan National University had a German speaker on this issue of post-unification migration. He noted that it was 20% of the entire ex-GDR population, slowed only by moving the capital to the east, an option a unified Korea would not likely entertain. I have written this up on my blog (October 22, 2010), and the Project might like to contact the speaker.

Migration-deterring notions like an internal passport or temporary work permits for Northerners in the South would appear terribly immoral, suggest North Koreans are second-class citizens, embarrass Korea before global opinion, and fire revanchist Northern political entrepreneurs. Once the DMZ is open, it will be politically near-impossible to reclose it without North Korea turning into something like the West Bank, a semi-occupied wild west zone in legal limbo, or a gigantic SEZ for the chaebol. Either way, it would appear so immoral before global opinion, and ‘illegal internal immigration’ would be so persistent, that I cannot imagine it will work.

I've blogged here about South Korea's emergent status as a country of immigration, at least as early as September 2009 and most recently earlier this month. The idea that North Korea may become a major source of immigrants is something that makes perfect sense to me, given the dysfunction in the North as contrasted to the prosperity in the South and assuming the reunification of the Korean peninsula--as I wrote in March 2010, very many North Koreans will want to head south. I've also written in November 2010 about how the contrast between a relatively multicultural South and a North that prides itself on ethnic purity may already be complicating intra-Korean relations, and may complicate relations significantly if Korea is reunified.

South Korea, as I noted, is becoming a place that people are moving to. North Korea, in the 21st century, is going to be a place that people are from. I don't think economic convergence with the south if reunification occurs is going to proceed at anything like the speed necessary for anything but the maintenance of the inter-Korean border to prevent large-scale migration south. As I noted in March 2010, North Koreans can go elsewhere, too, whether to adjacent China, Russia, Japan or points beyond. Last September here in Toronto, local news media covered the mass wedding of 15 refugee couples from North Korea at Toronto City Hall--see the tabloid Toronto Sun and the broadsheet Toronto Star for examples.

Labels:

economics,

ethnicity,

korea,

migration,

north korea,

politics,

south korea

Tuesday, February 21, 2012

Some population-related links

Over the past couple of months, I've collected links to blog posts on population-related issues. I present them here to you.

- In an extended essay at Geocurrents, Martin Lewis describes "The Many Armenian Diasporas, Then and Now". The most recent diasporas, first a mass migration from Anatolia after the Armenian genocide then economic migration from post-Soviet Armenia in the 1990s, were products of war. Earlier Armenian diasporas, however, were triggered by positive incentives to migrate, establishing mercantile networks stretching from central Europe to South Asia.

- After a half-century or so, Brazil is starting to become a noteworthy destination for immigrants, rather than a source. Jim Russell at Burgh Diaspora concentrates on one element of this, in the growing attractiveness of São Paulo to New Yorkers looking for the next global city.

- Patrick Metzger at the Toronto-centered blog Torontoist reacts to findings from the 2011 Canadian census revealing that Alberta's population has been growing significantly faster than Ontario, and that for the first time, more Canadians outside of Ontario live west of the province than east (in Québec and Atlantic Canada). To what extent is this shift product of Albertan growth as opposed to Ontarian decline? The debate's ongoing.

- Another post at Geocurrents notes the recent acceleration in population growth in Saskatchewan, perhaps connected with new energy developments. Will rapid population growth shift that Canadian province's traditionally left-wing political culture?

- At Crooked Timber, Maria Farrell's thoughtful personal essay "Things I have learnt from and about IVF" describes her own experiences with assisted reproduction.

- Two posts at Eastern approaches, the Economist's central and eastern Europe blog, deal with ethnic tensions in the Baltic States complicated by transnational ties. The first, on the recent referendum in Latvia on giving Russian official status, describes the polarization in Latvian society on ethnolinguistic lines that acts as a significant complication. The second, on growing Polish-Lithuanian tensions over Lithuania's Polish minority, makes the point that despite the two countries' shared history ion Poland-Lithuania they perceive this history in different ways. Rapid population aging and shrinkage in Lithuania, too, may--as commenters point out--encourage more of a siege mentality.

- A Victor Mair post at Language Log explores tensions in Hong Kong between Hong Kongers and mainland Chinese, often recent migrants to the autonomous city-state, with the two different populations being marked by the literal shibboleth of dialect: Cantonese-speaking Hong Kongers versus Putongua-speaking Chinese. Interesting and worrying stuff.

Friday, December 30, 2011

A note on ethnic conflict and demographics: the Czech Republic

The population of the Czech Republic is similar to that of most European populations in its broad outlines: long life expectancies, below-replacement fertility rates, more-or-less substantial net immigration, all can be found in the Czech Republic. The most notable distinguishing factor of the Czech Republic's demographics lie in its size, now and in the relatively distant past: the Czech Republic is one of the very few countries in the world with a smaller population now than in 1945.

The population of the Czech Republic reached a peak of nearly 11.2 million in 1940 but fell to a mere 8.8 million in 1947, not as a consequence of an especially high wartime death rate but rather primarily because of the expulsion of the roughly three million Sudeten Germans. The population has since grown to 10.5 million, this growth the product first of post-war natural increase then--despite a recent partial recovery in fertility rates--because of substantial net immigration.

Beginning with post-war internal migrants from Slovakia (Slovaks and Roma alike) to the labour-hungry Czech lands, immigration into the Czech Republic became more globalized with a later wave of Vietnamese immigrants who made use of Communist Czechoslovakia's recruitment of Vietnamese students and guest workers in the 1970s and 1980s, to the Ukrainians who left their country in the 1990s to earn a living in a neighbouring country with a strong labour market and permeable borders. (As an aside, I wonder if the Ukrainian presence in the Czech Republic is at all linked to historical Czech interactions with the Carpathian Ruthenia that was historically almost an eastern extension of Slovakia, specifically with the Zakarpattia Oblast that was actually part of Czechoslovakia from independence until its 1945 cession to the Soviet Union.) Bulgarians, Chinese, Russians, and Mongolians are some of the newer groups to appear in the Czech Republic. As a high-income European country the Czech Republic would already be an attractive destination, but that the cultural links maintained by the Czechs with other Slavic populations in central and eastern Europe and the Communist-era political and military links established with countries such as Vietnam and Mongolia has advantaged the Czech Republic relative to its neighbours. From what I can tell, this immigration has been substantially less politically problematic than in most other European countries.

None of this couldt have been the case without the catastrophic ethnic violence of the 1940s, the Nazis' colonization and brutalization of the Czechs being followed by the expulsion of nearly the entire ethnic German population from the Czech Republic's territory after the Nazi defeat. Ethnic conflict determined the demographics of the Czech Republic.

Let's start with immigration. Over at my blog I note that Czechoslovakia came apart so quickly and peacefully because Czechs and Slovaks weren't particularly close, for good and for ill; mild resentments and a certain romantic nostalgia characterized, and characterize, relations between the two largest ethnic groups in the former Czechoslovakia. Czechs and Slovaks were separate groups, and each had its own discrete territory unthreatened by the other. The same wasn't true for Czechs and Germans in the modern Czech Republic. I've argued at my blog that the expulsion of the Sudeten Germans was only possible because of long-standing Czech fears that German influence could be the death of their nation, whether metaphorically through assimilation or actually through genocidal colonization. After the Second World War, the expulsion of the Sudeten Germans was probably inevitable. In a counterfactual scenario where the expulsion of the Sudeten Germans wasn't nearly so complete, where the border regions of the Czech Republic were bicultural if not outright German-majority, I can imagine immigration being a contentious issue. In Québec, immigration has been controversial because of concerns about the impact of immigrants on the language balance. Would the post-Communist immigration-driven population growth of the Czech Republic been possible otherwise?

The demographic and economic geography of the Czech Republic would also be radically different. Before 1945, the population density of the Czech lands was relatively uniform, with many of the Czech lands' borders--the same borders home to the Sudeten Germans--being superbly industrialized. The expulsions changed this, depopulating the areas once populated by Germans and then repopulating them only partially with migrants from elsewhere in Czechoslovakia, the expulsions additionally undermining once-strong regional economies. The net result was to make population, making wealth and industry concentrate that much more strongly in the centre of the Czech Republic, in Prague and environs, and in turn creating peripheries. Some people have noted that these peripheries, in turn, suffered disproportionately from overindustrialization and pollution, as the regions' unsentimental new residents saw their new home as a space where industrial modernity could operate untrammelled by tradition, as a site for mass production and mass consumption regardless of the human and environmental cost. According to a recent study (PDF format), the regions which saw the strongest divergence from Czech and European Union averages (as measured by GDP per capita, not by household income) were the border regions that formed the core of the former German zone of settlement. This peripheralization, coupled with the only partial repopulation of the Czech republic's peripheries after 1945, could plausibly encourage the continued concentration of Czechs and their wealth in the geographic centre of their country. Could these border regions of the Czech Republic have evolved very differently if not for the replacement of their populations?

In the past at Demography Matters, we've looked at how changing norms of gender, trivial connections formed by flows of guest workers or tourists, political concerns, the different ways in which people form families, similarities of language and culture between different populations, even geographic adjacency have led to demographic change of one kind or another. One thing that I don't think that we've ever before taken a look at is the role of ethnic conflict, culminating in ethnic cleansing and even genocide, in triggering demographic change. Thinking about this, I find it more than a bit disturbing since more than a few of the populations we've taken a look at--in Germany, Poland, East Africa, the former Yugoslavia, of course the Czech Republic--have been very strongly influenced by the long-term consequences of ethnic conflict. This will change in the new year.

The population of the Czech Republic reached a peak of nearly 11.2 million in 1940 but fell to a mere 8.8 million in 1947, not as a consequence of an especially high wartime death rate but rather primarily because of the expulsion of the roughly three million Sudeten Germans. The population has since grown to 10.5 million, this growth the product first of post-war natural increase then--despite a recent partial recovery in fertility rates--because of substantial net immigration.

Beginning with post-war internal migrants from Slovakia (Slovaks and Roma alike) to the labour-hungry Czech lands, immigration into the Czech Republic became more globalized with a later wave of Vietnamese immigrants who made use of Communist Czechoslovakia's recruitment of Vietnamese students and guest workers in the 1970s and 1980s, to the Ukrainians who left their country in the 1990s to earn a living in a neighbouring country with a strong labour market and permeable borders. (As an aside, I wonder if the Ukrainian presence in the Czech Republic is at all linked to historical Czech interactions with the Carpathian Ruthenia that was historically almost an eastern extension of Slovakia, specifically with the Zakarpattia Oblast that was actually part of Czechoslovakia from independence until its 1945 cession to the Soviet Union.) Bulgarians, Chinese, Russians, and Mongolians are some of the newer groups to appear in the Czech Republic. As a high-income European country the Czech Republic would already be an attractive destination, but that the cultural links maintained by the Czechs with other Slavic populations in central and eastern Europe and the Communist-era political and military links established with countries such as Vietnam and Mongolia has advantaged the Czech Republic relative to its neighbours. From what I can tell, this immigration has been substantially less politically problematic than in most other European countries.

None of this couldt have been the case without the catastrophic ethnic violence of the 1940s, the Nazis' colonization and brutalization of the Czechs being followed by the expulsion of nearly the entire ethnic German population from the Czech Republic's territory after the Nazi defeat. Ethnic conflict determined the demographics of the Czech Republic.

Let's start with immigration. Over at my blog I note that Czechoslovakia came apart so quickly and peacefully because Czechs and Slovaks weren't particularly close, for good and for ill; mild resentments and a certain romantic nostalgia characterized, and characterize, relations between the two largest ethnic groups in the former Czechoslovakia. Czechs and Slovaks were separate groups, and each had its own discrete territory unthreatened by the other. The same wasn't true for Czechs and Germans in the modern Czech Republic. I've argued at my blog that the expulsion of the Sudeten Germans was only possible because of long-standing Czech fears that German influence could be the death of their nation, whether metaphorically through assimilation or actually through genocidal colonization. After the Second World War, the expulsion of the Sudeten Germans was probably inevitable. In a counterfactual scenario where the expulsion of the Sudeten Germans wasn't nearly so complete, where the border regions of the Czech Republic were bicultural if not outright German-majority, I can imagine immigration being a contentious issue. In Québec, immigration has been controversial because of concerns about the impact of immigrants on the language balance. Would the post-Communist immigration-driven population growth of the Czech Republic been possible otherwise?

The demographic and economic geography of the Czech Republic would also be radically different. Before 1945, the population density of the Czech lands was relatively uniform, with many of the Czech lands' borders--the same borders home to the Sudeten Germans--being superbly industrialized. The expulsions changed this, depopulating the areas once populated by Germans and then repopulating them only partially with migrants from elsewhere in Czechoslovakia, the expulsions additionally undermining once-strong regional economies. The net result was to make population, making wealth and industry concentrate that much more strongly in the centre of the Czech Republic, in Prague and environs, and in turn creating peripheries. Some people have noted that these peripheries, in turn, suffered disproportionately from overindustrialization and pollution, as the regions' unsentimental new residents saw their new home as a space where industrial modernity could operate untrammelled by tradition, as a site for mass production and mass consumption regardless of the human and environmental cost. According to a recent study (PDF format), the regions which saw the strongest divergence from Czech and European Union averages (as measured by GDP per capita, not by household income) were the border regions that formed the core of the former German zone of settlement. This peripheralization, coupled with the only partial repopulation of the Czech republic's peripheries after 1945, could plausibly encourage the continued concentration of Czechs and their wealth in the geographic centre of their country. Could these border regions of the Czech Republic have evolved very differently if not for the replacement of their populations?

In the past at Demography Matters, we've looked at how changing norms of gender, trivial connections formed by flows of guest workers or tourists, political concerns, the different ways in which people form families, similarities of language and culture between different populations, even geographic adjacency have led to demographic change of one kind or another. One thing that I don't think that we've ever before taken a look at is the role of ethnic conflict, culminating in ethnic cleansing and even genocide, in triggering demographic change. Thinking about this, I find it more than a bit disturbing since more than a few of the populations we've taken a look at--in Germany, Poland, East Africa, the former Yugoslavia, of course the Czech Republic--have been very strongly influenced by the long-term consequences of ethnic conflict. This will change in the new year.

Labels:

czech republic,

eastern europe,

ethnicity,

europe,

germany,

migration,

politics,

ukraine,

vietnam,

war

Friday, April 29, 2011

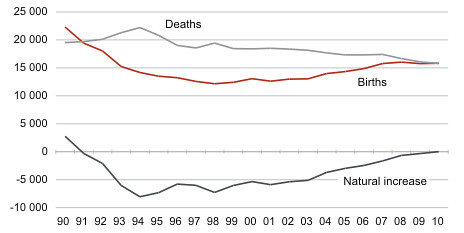

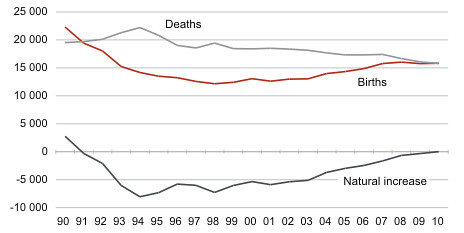

What last year's natural increase in Estonia means

Thanks to Facebook's Urmas for letting me know the surprising news that Estonia has become--so far as I know--the first former Soviet republic in Europe (Azerbaijan and the rest of the Caucasus, perhaps, excluded--thanks for the correction, Anatoly) to experience an excess of births over deaths since the fall of the Soviet Union. Yes, there seems to have been some improvement--I posted recently about Russia, after all--but it still stands out remarkably. Compare neighbouring Latvia's ongoing collapse.

Harju County's is Estonia's most populous, its 524 thousand people amounting to 39.2% of the Estonian population, while Tartu County is Estonia's third most populous, home to just shy of 150 thousand people and 11.2% of the total population.

It's noteworthy that Idu-Viru County, Estonia's third by population and located in the northeast of the country around the city of Narva on the Russian frontier, does not figure in this; so far as I know, Ida-Viru is continuing to experience continued natural decrease.

One of the most important facts about Estonian demographics is the ethnic cleavage between ethnic Estonians (now roughly 70% of the total, up from 60% in 1990) and Russophones, largely descended from Soviet-era migrants attracted to industrial jobs and a higher standard of living than they could find in other Soviet republics like Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. See this 2007 post from Itching for Eestimaa for a decent overview of the situation. The two populations behave differently in many ways, including in demographic patterns. The three most populous counties fit into three different categories, Harju being roughly 60% ethnically Estonian by population, Tartu ~85%, but Ida-Viru 20%. (Somewhat ethnically mixed up to the Soviet era, post-war displacement of ethnic Estonians and mass immigration to the northeast's industrial centres created the only one of Estonia's fifteen counties with a non-Estonian majority population.)