Showing posts with label first nations. Show all posts

Showing posts with label first nations. Show all posts

Tuesday, June 09, 2015

Some migration-related news links

Labels:

africa,

algeria,

angola,

armenia,

brazil,

emigration,

first nations,

france,

immigration,

islands,

links,

mexico,

migration,

nigeria,

portugal,

syria,

united states,

west africa

Thursday, May 26, 2011

Why Mongolia's set for massive urbanization

I owe thanks to Sublime Oblivion's Anatoly Karlin for linking to Kit Gillet's article in the Guardian, "Vast Mongolian shantytown now home to quarter of country's population". It turns out that over the past two decades, the Mongolian capital of Ulan Bator, has grown immensely, developing shantytowns as the traditional nomadic herding lifestyle of the Mongols becomes non-viable and despite the influx of funds from Mongolia's new mines.

None of this should be a surprise. Dutch sociologist Paul Treanor's 2001 essay "Mongolia and Wyoming/Montana" predicted this very outcome. In the previous essay, Treanor compared the very poor Mongolia with the very rich American states of Wyoming and Montana. Mongolia and Wyoming/Montana, Treanor observes, are both territories which compare closely "in terms of climate, altitude, vegetation and population density". What are the differences?

Treanor goes on to point out that Mongolia is far more removed from the major population centres of Eurasia than Wyoming and Montana are from the population centres of North America, that the relative cultural uniformity of the United States makes migration to and from Wyoming and Montana more possible than migration to and from Montana, that the tourism industry that thrives in Wyoming and Montana barely exists in Mongolia, and--crucially--that Mongolia is not part of a federal state that could subsidize its peripheral areas. At the same time, the nomadic herding lifestyle of the Mongols is becoming increasingly unsustainable, not least because of the quadrupling of the Mongolian population over the past hundred years. Arguably, most of Mongolia is too marginal to sustain local populations. The consequence of all this?

In all honesty, I don't see anything wrong with this. Leaving aside a lack of obvious sources of subsidies to rural Mongolia--Soviet subsidization of Mongolia was product of, among other things, Sino-Soviet tensions and an ideological commitment to support a long-standing Communist state and satellite--I agree with Treanor that expecting the bulk of Mongolians to remain employed in increasingly non-viable regions and lifestyles is unacceptable.

Mongolia has to change if Mongolians are to enjoy acceptable standards of living. The job of the Mongolian government and its partners is to ensure that the transition is made as efficiently and quickly as possible. If not, mass emigration is always a possibility, whether to a China that's rapidly industrializing and is home to almost twice as many ethnic Mongols as in Mongolia, to a Russia that has long-standing connections with Mongolia and its own labour shortages, or to a South Korea that has cultivated close economic and demographic ties with Mongolia.

Stretching north from the capital, Ulan Bator, an endless succession of dilapidated boundary markers criss-cross away into the distance.

They demarcate a vast shantytown that sprawls for miles and is now estimated to be home to a quarter of the entire population of Mongolia.

More than 700,000 people have crowded into the area in the past two decades. Many are ex-herders and their families whose livelihoods have been destroyed by bitter winters that can last more than half the year; many more are victims of desertification caused by global warming and overgrazing; the United Nations Development Programme estimates that up to 90% of the country is now fragile dryland.

Yet with limited education, few transferable job skills and often no official documents, most end up simply waiting, getting angry with the government and reminiscing about nomadic lives past. Many take to alcohol.

"More and more people arrive every year and there are so few jobs available," said Davaasambuu after queueing for 30 minutes to collect his family's daily drinking water from one of 500 water stations that dot the slum. "Nothing has changed in my neighbourhood since the last election [in May 2009]. There have been no new jobs or improvements. One little bridge has been added in the last four years, that's it," he said.

[. . .]

[W]hen temperatures plummet into the minuses for up to eight months, poorer residents are forced to spend upwards of 40% of their income on wood or coal for heating, which adds to their financial burden as well as to the heavy clouds of pollution that hangs over the city. Roads are simple, unpaved mud paths and streets have no signs, streetlights or even names but are merely the gaps naturally placed between two rows of tents or shacks set up by newly arrived migrants without any input from the government.

"The quality of the infrastructure is a major problem," said Mesky Brhane, a senior urban specialist with the World Bank, who helped produce last year's report. "[People] are clearly frustrated by the lack of infrastructural improvements by the government.

[. . .]

Even in the more central ger areas, where many residents have lived for over a decade and built more permanent wooden or brick houses, running water and central heating are unavailable and the streets remain dark, mud roads with open sewage streams and rubbish piled high.

Another big concern is the level of unemployment. While tens of thousands of rural migrants flood the city every year looking for work, setting up their tents at the point where last year's migrants stopped, unemployment remains a critical issue, especially in the ger districts where the unemployment rate can be as high as 62%, compared with 21% in the more developed areas of the capital.

None of this should be a surprise. Dutch sociologist Paul Treanor's 2001 essay "Mongolia and Wyoming/Montana" predicted this very outcome. In the previous essay, Treanor compared the very poor Mongolia with the very rich American states of Wyoming and Montana. Mongolia and Wyoming/Montana, Treanor observes, are both territories which compare closely "in terms of climate, altitude, vegetation and population density". What are the differences?

Density in both areas is very low by European standards. (In the European Union 8 inhabitants/km2 is the threshold for regional assistance to low-density areas). The Gobi desert is an empty area on any map of world population density. There are some almost empty areas in central Montana, and in semi-desert south-west Wyoming. Nevertheless, the rail infrastructure in the US is better than in Mongolia, and the local road network far better. The same will apply to energy infrastructure, and above all to the 'social infrastructure' such as schools and health care.

Increasingly, however, both regions have the same economic basis: mining. No major industry ever developed in Wyoming and Montana anyway: and in Mongolia the non-extractive industrial sector has collapsed. So there has been a certain convergence of the economic base - but that base is better developed in the two US states anyway. Although reports on Mongolia refer to the 'massive' Soviet-built coal mines, Wyoming produces far more coal (over 300 million tons). In reality Mongolia's coal production (and per capita use) is tiny, in comparison with the US. Montana has a 120-year history as a copper-mining state. Both states are also well ahead of Mongolia, in the development of hydroelectric power.

In Montana, agriculture is a larger sector than mining, - but part of the state has better climate and soils than any area of Mongolia. 18 % of Montana is arable land (concentrated in the north-east corner), compared with only 1% in Mongolia. Wyoming is, like Mongolia, about 75% grazing land.

General agricultural productivity on Mongolian territory is very low. Compare Mongolia with agriculture in Poland (still considered a low-productivity agricultural sector in comparison with western Europe). In 1997, total cereal production per km2 was about 525 times higher in Poland. Meat production per km2 was 50 times higher in Poland. These figures are for total land area, and reflect primarily the difference in climate, geography, and ecology. In fact much of Mongolia is 'agricultural land', perhaps more than in Poland, but only in the sense that herds sometimes graze there. It took about 40% of the population to reach even that level of meat production. Cereal production was concentrated on the Soviet-built state farms. It has collapsed since 1989, from 416 kg/person to 81 kg/person, despite the present cereal shortage. That suggests that even these farms were only viable with subsidies, and outside technical assistance.

The low agricultural productivity reflects the harsh climate of Mongolia. In fact the combination of cold and aridity is probably harsher than in Wyoming and Montana. In relation to the ecological limitations, the inhabitants had successfully adapted to these harsh conditions. The system of pastoral nomadism in Mongolia emerged over a period of thousands of years, along with others in the Eurasian steppes and deserts. It survived almost unchanged until about 1910. There was no similar range of pastoral nomadic cultures in North America.

In other words, there was in Mongolia a unity of culture, history, economy and society based on pastoral nomadism. There was a pastoral-nomadic economy, in a pastoral-nomadic society, with a pastoral-nomadic type of culture, and a history characteristic for Eurasian steppe nomads. Mongolia is still inhabited by people who are culturally familiar with this unity: for many of them it is still daily reality. People outside Mongolia are also vaguely familiar with it: at least, they can associate Mongolia with yak herds, nomad tents, and Ghengis Khan.

In contrast, the original inhabitants of Wyoming and Montana were militarily defeated, and marginalised for generations. (The Indian Reservations are known, even outside the United States, as examples of marginalisation). An entirely new society and economy was substituted for the existing version. The new population came primarily from rural Europe: for them, food production meant primarily the family farm. During the 19th century, the immigrants developed a cultural adaptation to the steppe/prairie zone: the cattle ranch. Although the cattle (and the horses) were imports from Eurasia, the system worked. But despite all the great cowboy mythology, the settlement of the American west was not primarily based on ranching. It certainly could not be based on ranching today: the ranch population is now a fraction of the state total.

Treanor goes on to point out that Mongolia is far more removed from the major population centres of Eurasia than Wyoming and Montana are from the population centres of North America, that the relative cultural uniformity of the United States makes migration to and from Wyoming and Montana more possible than migration to and from Montana, that the tourism industry that thrives in Wyoming and Montana barely exists in Mongolia, and--crucially--that Mongolia is not part of a federal state that could subsidize its peripheral areas. At the same time, the nomadic herding lifestyle of the Mongols is becoming increasingly unsustainable, not least because of the quadrupling of the Mongolian population over the past hundred years. Arguably, most of Mongolia is too marginal to sustain local populations. The consequence of all this?

[T]he entire pattern of settlement is both artificial and dependent on a base population of herders. It there is no nomadic herding, then there is little reason for anyone to live in zones of natural pasture. It the clusters of nomadic herding population disappear, then many [small] centres then lose their reason for existence. In turn, most aimak centres exist primarily as second-tier service centres, and if the base population migrates, their local economy would also collapse.

The Gobi population is small enough, in absolute terms, to fit into a few mining and oil towns. In contrast, the forest-steppe zone will probably lose much of its population. Why this prediction? It is extremely unlikely that the nomadic pastoral lifestyle will survive for another generation: overall productivity is extremely low. If a high-productivity form of meat production replaced nomadic herding, the rural population might be partly stabilised. If not, then the rural population will have the choice of staying where they are, as the poorest people in Asia - or migrating. Given the predicted growth of the Chinese economy, and the demographic labour shortage in Russia and western Europe, emigration will probably be easier than at present. A special case is the Bayan-Ölgiy aimak: the population is mainly Kazakh. There has already been some migration to Kazakhstan: an oil boom there might attract much of the remaining Kazakh population.

[. . .]

The exceptional status of Ulaan Bataar is obvious. The industrial centres Darhan, Erdenet and (on a smaller scale Choibalsan), are the result of planned concentration of investment. They were created by decisions at national level. That is also true for the aimak centres, with primarily a service function. Industrialisation of the aimak centres seems improbable. They are remote and relatively small, with no existing industry, except processing meat and hides. Their 'gross product' is comparable to agricultural villages in western Europe. They will probably be much the same size in 2025 - about 15 000 to 25 000 inhabitants.

That leaves Ulaan Bataar. The most reasonable prediction of the future population distribution is that the majority of Mongolians will live in one city. At present the best example of 'primate city' growth is Tirana in Albania. That is also a country with extreme rural poverty, and a collapsed industrial sector. Tirana has doubled (perhaps tripled) its population in a decade. However Albania also has a rich neighbour, Italy, and an extremely high rate of illegal emigration. And it has an urban tradition in the coastal regions, and an existing urban hierarchy with regional centres. Mongolia's medium-term future is extreme rural poverty, little emigration, and 100% concentration of development in Ulaan Bataar. That suggests massive movement to the capital.

In all honesty, I don't see anything wrong with this. Leaving aside a lack of obvious sources of subsidies to rural Mongolia--Soviet subsidization of Mongolia was product of, among other things, Sino-Soviet tensions and an ideological commitment to support a long-standing Communist state and satellite--I agree with Treanor that expecting the bulk of Mongolians to remain employed in increasingly non-viable regions and lifestyles is unacceptable.

Mongolia has to change if Mongolians are to enjoy acceptable standards of living. The job of the Mongolian government and its partners is to ensure that the transition is made as efficiently and quickly as possible. If not, mass emigration is always a possibility, whether to a China that's rapidly industrializing and is home to almost twice as many ethnic Mongols as in Mongolia, to a Russia that has long-standing connections with Mongolia and its own labour shortages, or to a South Korea that has cultivated close economic and demographic ties with Mongolia.

Friday, April 08, 2011

Tuberculosis, Canadian first nations, and pandemics

Over at my blog, I linked to a startling news item pointing to the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science paper "Dispersal of Mycobacterium tuberculosis via the Canadian fur trade". The abstract?

This finding documents any number of things, such as the underlying and continuing vulnerability of Canada's indigenous peoples to epidemic disease, the long-standing ties between French Canadians--then, as commenters at CBC point out, simply Canadiens--and First Nations, the highly contingent nature of the transmission of pandemic diseases, and the extent to which these pandemics can remain below public attention for decades or even centuries. Parallels with the the evolution and spread of HIV, reconstructed from fossil viruses and genetic data, are entirely merited.

The lead author notes that in the case of tuberculosis, isolated early cases produced an epidemic only when living conditions deteriorated sharply from the late 19th century on, as traditional lands were confiscated, children sent to residential schools, and living conditions on reserve became--and remained--Third World. If these conditions didn't occur, then presumably tuberculosis would be much less of a problem on Canada's reserves.

Patterns of gene flow can have marked effects on the evolution of populations. To better understand the migration dynamics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, we studied genetic data from European M. tuberculosis lineages currently circulating in Aboriginal and French Canadian communities. A single M. tuberculosis lineage, characterized by the DS6Quebec genomic deletion, is at highest frequency among Aboriginal populations in Ontario, Saskatchewan, and Alberta; this bacterial lineage is also dominant among tuberculosis (TB) cases in French Canadians resident in Quebec. Substantial contact between these human populations is limited to a specific historical era (1710–1870), during which individuals from these populations met to barter furs. Statistical analyses of extant M. tuberculosis minisatellite data are consistent with Quebec as a source population for M. tuberculosis gene flow into Aboriginal populations during the fur trade era. Historical and genetic analyses suggest that tiny M. tuberculosis populations persisted for ∼100 y among indigenous populations and subsequently expanded in the late 19th century after environmental changes favoring the pathogen. Our study suggests that spread of TB can occur by two asynchronous processes: (i) dispersal of M. tuberculosis by minimal numbers of human migrants, during which small pathogen populations are sustained by ongoing migration and slow disease dynamics, and (ii) expansion of the M. tuberculosis population facilitated by shifts in host ecology. If generalizable, these migration dynamics can help explain the low DNA sequence diversity observed among isolates of M. tuberculosis and the difficulties in global elimination of tuberculosis, as small, widely dispersed pathogen populations are difficult both to detect and to eradicate.

This finding documents any number of things, such as the underlying and continuing vulnerability of Canada's indigenous peoples to epidemic disease, the long-standing ties between French Canadians--then, as commenters at CBC point out, simply Canadiens--and First Nations, the highly contingent nature of the transmission of pandemic diseases, and the extent to which these pandemics can remain below public attention for decades or even centuries. Parallels with the the evolution and spread of HIV, reconstructed from fossil viruses and genetic data, are entirely merited.

The data point to 1908 as the year that HIV group M (which now infects more than 31 million people worldwide) began its assault — somewhat earlier than the previous best estimate of 1931. Though 1908 is an approximation, the evidence suggests that the true date almost certainly falls sometime between 1884 and 1924.

When such evolutionary studies are overlaid with the history of human societies in Africa, a detailed picture of the origins of HIV group M comes into focus. Historically, chimpanzees in west-central Africa have been hunted for food. Many of them are also infected with the virus that HIV evolved from, Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV). Butchering chimps probably repeatedly exposed local hunters to SIV. The virus may have made the leap to infect people many times — but only at the turn of the century did this viral invasion gain a foothold in the population. Around that time, a hunter seems to have picked up the virus from a chimp in the southeast corner of Cameroon and carried the pathogen along the main route out of the forest at the time, the Sangha river, to Leopoldville (modern-day Kinshasa). Mirroring the growth of the cities in Africa, the virus spread slowly in Leopoldville until around 1950, when it began to proliferate rapidly. Still undetected, the virus continued to evolve and to diversify, leapfrogging through burgeoning cities. With the increasing ease of global travel, HIV was carried out of Africa and around the world — and the rest, as they say, is history.

This reconstruction of HIV's origins certainly satisfies our curiosity — but it also serves as a practical reminder of the conditions that foster the emergence of new diseases. We cannot stop evolution. Pathogens regularly make the leap to infect new hosts, and we increase our chances of being victimized by one of these host switches, when we take on lifestyles that put us in close contact with other species — especially ones closely related to us — like chimpanzees. The early history of HIV also illustrates that the virus is not invincible. For more than 50 years, HIV infected human populations but had such a small impact that it wasn't noticed against the backdrop of other diseases. In comparison to pathogens like malaria (which is carried by mosquitoes) and the common cold (which can travel through the air), HIV is pretty terrible at getting from one person to the next, relying on the direct transfer of body fluids. The virus only got its start in humans through a confluence of opportunity and history — the practice of hunting chimpanzees, the rise of densely populated cities in Africa, and a correlated increase in high-risk behaviors involving the exchange of body fluids (e.g., injection drug use, prostitution). The fact that changes in human societies were so critical in the rise of the virus suggests that changes in human societies could snuff it as well.

The lead author notes that in the case of tuberculosis, isolated early cases produced an epidemic only when living conditions deteriorated sharply from the late 19th century on, as traditional lands were confiscated, children sent to residential schools, and living conditions on reserve became--and remained--Third World. If these conditions didn't occur, then presumably tuberculosis would be much less of a problem on Canada's reserves.

Labels:

canada,

disease,

first nations,

french canada,

migration

Wednesday, March 23, 2011

A profile of Tōhoku

I'd like to start by reiterating the point of Edward's post Sunday, about the likelihood of the earthquake triggering systemic changes in Japan. Certainly the recovery process will be long: Bloomberg's Shamin Adam suggests, after the World Bank, that it might take five years for Japan to finish rebuilding.

My take? Curiously and quite unexpectedly, I learned that the afflicted region of Tōhoku in northern Honshu hosts--shades of the Taiwanese village of Houtong--a cat-loving island community. The first paragraphs of Wikipedia's article on Tashirojima suggest interesting parallels with Houtong. The two communities, it seems, are economically marginal with the decline of their previous extractive industries and facing rapidly population decline and aging, while cats are among the most famously enduring invasive species. When the people go, the cats remain.

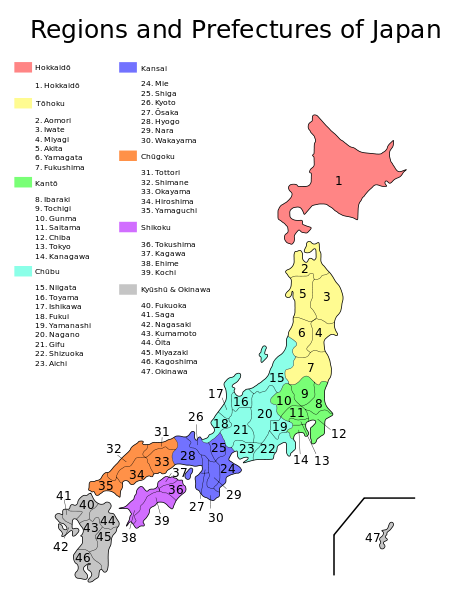

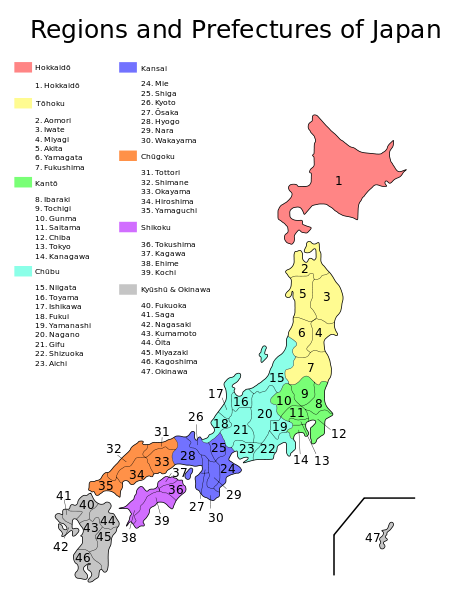

Tōhoku, a six prefecture region, has always been marginal, a relatively late addition to the Japanese ecumene.

Tōhoku was the last stronghold of the Emishi, a non-Japanese people linked to the pre-Yamato hunter-gatherer Jomon culture but eventually conquered and apparently assimilated by the 9th century CE. An interpretation of one recent DNA study of different regional populations in Japan might confirm that the Emishi left descendants in the current population of Tōhoku, noted as containing relatively fewer Yamato migrants than populations in western Japan. (Might.) Distant from the main centres of population and resources in western Japan, Tōhoku remained something of a frontier for a long time. In terms of the inhabitants' spoken language, for instance, the people were mocked for their thick dialect within Japan and without, the lower and deviant status of the Tōhoku dialect remaining still. Apparently the rustic character of Hagrid in the Harry Potter series has his speech rendered in Tōhoku dialect.

Tōhoku has become increasingly marginalized within Japan, in terns of its relative heft. Proof of this is easy enough to come by, since most of Tōhoku is included in the historical unit of Mutsu Province, which gathered together what is now the prefectures of Aomori, Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima along with two municipalities in the Sea of Japan-facing Akita Prefecture (Kazuno and Kosaka). (These last two municipalities, combined have a population a bit more than a half-percent of the four prefectures entirely in the former Mutsu.)

The region has under sustained relative, even absolute decline, for centuries. The most populous Japanese province at the beginning of the Shogunate, ranking behind only the Musashi province that included Tokyo, towards the end of the end of the Shogunate the two provinces switched positions. Mutsu suffered severely from famine-associated mortality crises in the mid-18th and early 19th centuries, its population falling absolutely and Mutsu's proportion of the Japanese population declining steadily from 7.5% in the 1721 population survey to 6.9% in the first Meiji census in 1873 census. The population of the Mutsu region did more than triple in the half-dozen generations to the 2010 survey, to reach 7.1 million in 2010, but its share of the total Japanese population slide further to 5.6% as of 2010. If not for the Meiji-era colonization of Hokkaido--up until the last quarter of the 19th century an island barely integrated into the Japanese political framework and populated by only a hundred thousand people--Tōhoku's gradual decline might have become that much more visible. As is, the region contains some of the least densely populated areas in the country, as Scott's map shows nicely.

This all brings us back to the question of the future of Japan. As a relatively rural and agricultural region, Tōhoku traditionally supported the Liberal Democratic Party, which whatever its other flaws at least continued to channel investments in local infrastructure. Scandals about misinvested funds and fundamental doubt helped Tōhoku transfer its loyalties to the Democratic Party.

One certain consequence of the disaster in Tōhoku is its destruction of the old order. Tashirojima might survive by dint of the tourism value of its cats, but how many of the small agricultural and fishing villages wrecked by the disaster will come back? Where will the money come from? Where will the people come from? Will even the regional metropole of Sendai regain its position relative to other Japanese cities less favoured by disaster? As Spike Japan's Richard Hendy pointed out, the devastation visiting not only on the Fukishima complex but on the other electric plants in eastern Japan, along with the region's power grid separate from western Japan's, means that Tōhoku--not to mention the rest of Japan--will be short of electricity, that most basic force of post-industrial civilization, for months if not years. As Charlie Stross noted in a separate post, the shortages of electricity ensure the premature deaths of thousands of vulnerable people deprived of air conditioning this summer, as far south as greater Tokyo.

Tōhoku doesn't have the resources to recover its pre-disaster levels. Japan likely doesn't have the resources necessary to let Tōhoku recover fully, and almost certainly lacks now and will continue to lack the interest in doing so given its other challenges. Tōhoku, I predict, has peaked: the long relative decline it began under the shoguns and continued through Meiji and the eventful 21st century will only accelerate, new reasons added to the many old for the decline of rural and marginal Japan that Hendy describes in his blog. The Japan Statistical Yearbook shows that the region's prefectures have been exporting people in large numbers for the past decade. Why will this slow down? Humans may be less resilient than cats, but then again, humans rightfully demand much more from their environment than their pets. Tashirojima's cats may well thrive long after Tashirojima's people have departed to whatever destination.

My take? Curiously and quite unexpectedly, I learned that the afflicted region of Tōhoku in northern Honshu hosts--shades of the Taiwanese village of Houtong--a cat-loving island community. The first paragraphs of Wikipedia's article on Tashirojima suggest interesting parallels with Houtong. The two communities, it seems, are economically marginal with the decline of their previous extractive industries and facing rapidly population decline and aging, while cats are among the most famously enduring invasive species. When the people go, the cats remain.

Tashirojima (田代島?) is a small island in Ishinomaki City, Miyagi Prefecture, Japan. It lies in the Pacific Ocean off the Oshika Peninsula, to the west of Ajishima. It is an inhabited island, although the population is quite small (around 100 people, down from around 1000 people in the 1950s). It has become known as "Cat Island" due to the large stray cat population that thrives as a result of the local belief that feeding cats will bring wealth and good fortune. The cat population is now larger than the human population on the island. (A 2009 article in Sankei News says that there are no pet dogs and it is basically prohibited to bring dogs onto the island.)

[. . .]

Since 83% of the population is classified as elderly, the island's villages have been designated as a "terminal villages" (限界集落) which means that with 50% or more of the population being over 65 years of age, the survival of the villages is threatened. The majority of the people who live on the island are involved either in fishing or hospitality.

Tōhoku, a six prefecture region, has always been marginal, a relatively late addition to the Japanese ecumene.

Tōhoku was the last stronghold of the Emishi, a non-Japanese people linked to the pre-Yamato hunter-gatherer Jomon culture but eventually conquered and apparently assimilated by the 9th century CE. An interpretation of one recent DNA study of different regional populations in Japan might confirm that the Emishi left descendants in the current population of Tōhoku, noted as containing relatively fewer Yamato migrants than populations in western Japan. (Might.) Distant from the main centres of population and resources in western Japan, Tōhoku remained something of a frontier for a long time. In terms of the inhabitants' spoken language, for instance, the people were mocked for their thick dialect within Japan and without, the lower and deviant status of the Tōhoku dialect remaining still. Apparently the rustic character of Hagrid in the Harry Potter series has his speech rendered in Tōhoku dialect.

Tōhoku has become increasingly marginalized within Japan, in terns of its relative heft. Proof of this is easy enough to come by, since most of Tōhoku is included in the historical unit of Mutsu Province, which gathered together what is now the prefectures of Aomori, Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima along with two municipalities in the Sea of Japan-facing Akita Prefecture (Kazuno and Kosaka). (These last two municipalities, combined have a population a bit more than a half-percent of the four prefectures entirely in the former Mutsu.)

The region has under sustained relative, even absolute decline, for centuries. The most populous Japanese province at the beginning of the Shogunate, ranking behind only the Musashi province that included Tokyo, towards the end of the end of the Shogunate the two provinces switched positions. Mutsu suffered severely from famine-associated mortality crises in the mid-18th and early 19th centuries, its population falling absolutely and Mutsu's proportion of the Japanese population declining steadily from 7.5% in the 1721 population survey to 6.9% in the first Meiji census in 1873 census. The population of the Mutsu region did more than triple in the half-dozen generations to the 2010 survey, to reach 7.1 million in 2010, but its share of the total Japanese population slide further to 5.6% as of 2010. If not for the Meiji-era colonization of Hokkaido--up until the last quarter of the 19th century an island barely integrated into the Japanese political framework and populated by only a hundred thousand people--Tōhoku's gradual decline might have become that much more visible. As is, the region contains some of the least densely populated areas in the country, as Scott's map shows nicely.

This all brings us back to the question of the future of Japan. As a relatively rural and agricultural region, Tōhoku traditionally supported the Liberal Democratic Party, which whatever its other flaws at least continued to channel investments in local infrastructure. Scandals about misinvested funds and fundamental doubt helped Tōhoku transfer its loyalties to the Democratic Party.

In Tohoku, the northern part of Japan’s biggest island, Honshu, and the home of Democrat founder and former leader Ichiro Ozawa, the beating was also fierce, if not quite as emphatic, as the LDP took 9 seats and the Democrats 26.

“Tohoku is generally conservative, with farmers supporting the LDP’s policies. But before the election their attitude had changed,” said Masaki Hara, a retired Sendai resident, who joined me watching results, along with many other captive ferry passengers, some of whom had lost interest in the Yomiuri Giants game on a competing TV screen.

Hara said citizens were questioning the value of big infrastructure projects, such as a subway line in Tohoku’s largest city of Sendai that had seen cost overruns, while doubting the Liberal Democratic Party’s vision.

“I don’t like Ozawa, but I support his taking on the LDP.”

One certain consequence of the disaster in Tōhoku is its destruction of the old order. Tashirojima might survive by dint of the tourism value of its cats, but how many of the small agricultural and fishing villages wrecked by the disaster will come back? Where will the money come from? Where will the people come from? Will even the regional metropole of Sendai regain its position relative to other Japanese cities less favoured by disaster? As Spike Japan's Richard Hendy pointed out, the devastation visiting not only on the Fukishima complex but on the other electric plants in eastern Japan, along with the region's power grid separate from western Japan's, means that Tōhoku--not to mention the rest of Japan--will be short of electricity, that most basic force of post-industrial civilization, for months if not years. As Charlie Stross noted in a separate post, the shortages of electricity ensure the premature deaths of thousands of vulnerable people deprived of air conditioning this summer, as far south as greater Tokyo.

Tōhoku doesn't have the resources to recover its pre-disaster levels. Japan likely doesn't have the resources necessary to let Tōhoku recover fully, and almost certainly lacks now and will continue to lack the interest in doing so given its other challenges. Tōhoku, I predict, has peaked: the long relative decline it began under the shoguns and continued through Meiji and the eventful 21st century will only accelerate, new reasons added to the many old for the decline of rural and marginal Japan that Hendy describes in his blog. The Japan Statistical Yearbook shows that the region's prefectures have been exporting people in large numbers for the past decade. Why will this slow down? Humans may be less resilient than cats, but then again, humans rightfully demand much more from their environment than their pets. Tashirojima's cats may well thrive long after Tashirojima's people have departed to whatever destination.

Labels:

animals,

economics,

first nations,

japan,

regions

Thursday, January 27, 2011

What the cats of Houtong say about the population of Taiwan

Back in September at my blog, I linked to an interesting news story describing how the Taiwanese village of Houtong, located just outside the capital of Taipei, has managed to find new life after its coal mining economy went under thanks to its large feral cat community.

I'll happily admit the article caught my attention because it dealt with cats. Since I got my own cat, Shakespeare, a bit more than two years ago, I've paid a lot of attention to the species and the genus.

This isn't just a cat photopost, mind. The ohenomenon of the cats of Houtong actually helps illustrate any number of interesting things about Taiwanese--and world--demographics.

1. Houtong is a community that was a one-industry town, dependent on coal mining. That source of income has disappeared, as cheaper foreign imports and perhaps a move away from coal as an energy source led to the industry's complete disappearance from Taiwan in 2001. Houtong is a community ultimately undermined by globalization. With three-quarters of Taiwan's population fertility rates drop and foreign women immigrate to compensate for a male-biased sex ratio.

One major theme of my Taiwan posts here has been the very low fertility rate, for the main the standard combination of patriarchal cultural norms with the substantial emancipation of women. Another theme has been the sex ratio strongly biased towards men, producing a deficit of marriageable women. Just as in South Korea, this has led to substantial marriage-driven immigration to Taiwan, as Hsieh and Wang describe in their paper, with women from mainland China and Southeast Asia--particularly but certainly not only Vietnamese women--contributing a

notable, if declining number and proportion of newborns.

Houtong is a small rural community; given the tendency of immigrant women to marry relatively low-status and economically marginal men in rural areas, it wouldn't be surprising if a disportionate number of wives there, like Sumarni, might be of foreign background. As this Wall Street Journal article on Taiwanese immigrant wives and their children points out, the village with the highest proportion of immigrant-mother children--17.5%--is Shihding, like Houtong a coal-mining village in rural Taipei County.

3. On a related note, the immigrant-wife phenomenon illustrates the diversity of the Taiwanese population. This diversity doesn't include only the Taiwanese aborigines who form 2% of the Taiwanese population, but the mainlander tenth of the Taiwanese population disproportionately concentrated in Taipei, along with the Min Nan/Fujianese-speaking Hoklo who form 70% of the Taiwanese population and the Hakka who form nearly a fifth of the population, alongside non-Chinese immigrants.

4. Incidentally, Houtong has become a tourism destination for tourists across greater China, i.e. China and Hong Kong and Macao as well as Taiwan. This may indicate the growing integration of Taiwan's population into the population of Greater China, as demonstrated not only by the Chinese immigrants to Taiwan but by the growing Taiwanese migrant population in mainland China, for instance the tens of thousands in Shanghai. China's not going to be the only reference point, as the Southeast Asia immigrants indicate, but it'll be quite important, arguably most important.

5. Finally, the demographics of the cat species are the dismal demographics that once afflicted the human species. Cats have a spectacularly high birth rate, bearing multiple litters with multiple kittens for most of their lives; female cats can actually become pregnant too early. Why, then are there not more cats out there? A terribly high death rate: indoor cats live for decades, outdoor cats for years. (Shakespeare's an indoor cat, if you're wondering.)

Thoughts?

Visitors' raves on local blogs have helped draw cat lovers to fondle, frolic and photograph the 100 or so resident felines in Houtong, one of several industrial communities in decline since Taiwan's railroads electrified and oil grew as a power source.

Most towns have never recovered, but this tiny community of 200 is fast reinventing itself as a cat lover's paradise.

"It was more fun than I imagined," said 31-year-old administrative assistant Yu Li-hsin, who visited from Taipei. "The cats were clean and totally unafraid of people. I'll definitely return."

On a recent weekday afternoon, dozens of white, black, grey and calico-coloured cats wandered freely amid Houtong's craggy byways, while visitors captured the scene with cellphone cameras and tickled the creatures silly with feather-tipped sticks.

I'll happily admit the article caught my attention because it dealt with cats. Since I got my own cat, Shakespeare, a bit more than two years ago, I've paid a lot of attention to the species and the genus.

This isn't just a cat photopost, mind. The ohenomenon of the cats of Houtong actually helps illustrate any number of interesting things about Taiwanese--and world--demographics.

1. Houtong is a community that was a one-industry town, dependent on coal mining. That source of income has disappeared, as cheaper foreign imports and perhaps a move away from coal as an energy source led to the industry's complete disappearance from Taiwan in 2001. Houtong is a community ultimately undermined by globalization. With three-quarters of Taiwan's population fertility rates drop and foreign women immigrate to compensate for a male-biased sex ratio.

Indonesian-born Sumarni, 35, who married a local man six years ago, says she is grateful to the tourists for relieving the town's isolation.

"My three-year-old daughter gets to play with some children of her age when visitors bring their kids here," she said. "There is really not any playmate of her age in the community."

Sumarni has also benefited financially from the tourist influx, piggybacking it to set up a profitable food stall next to her modest home.

One major theme of my Taiwan posts here has been the very low fertility rate, for the main the standard combination of patriarchal cultural norms with the substantial emancipation of women. Another theme has been the sex ratio strongly biased towards men, producing a deficit of marriageable women. Just as in South Korea, this has led to substantial marriage-driven immigration to Taiwan, as Hsieh and Wang describe in their paper, with women from mainland China and Southeast Asia--particularly but certainly not only Vietnamese women--contributing a

notable, if declining number and proportion of newborns.

The number of newborns born to foreign brides in Taiwan plunged to a low of 17,038 in 2009, reaching only 56 percent of a peak of 30,428 recorded in 2003, according to statistics compiled by the Bureau of Health Promotion under the Cabinet-level Department of Health. Foreign brides mainly refer to women from mainland China and Southeast Asian countries who marry Taiwanese men.

The ratio of their babies to the total number of newborns in Taiwan hit a high of 13.51 percent in 2003, meaning that one out of every seven to eight babies were born to such brides.

The ratio fell under the 10 percent mark in 2008 and declined further to only 8.58 percent in 2009, indicating that one out every 11 to 12 babies was born to foreign brides.

The figures have clearly demonstrated that the number of newborns born to foreign brides has been trending downward at a rapid pace.

Observers attributed the decline in the number of babies which foreign brides have given birth to in the past few years mainly to the decrease in the number of foreign brides over the years.

Taiwanese men used to be a priority husband target for women from Southeast Asian countries during the years of Taiwan's economic prosperity. But their willingness to marry Taiwanese men has been undermined by Taiwan's economic shrinkage in recent years.

Statistics compiled by the Ministry of the Interior showed that the number of registered alien brides hit a high of 48,600 in 2003, and then declined steadily to a low of only 18,241 in 2009, accounting for only 38 percent of the 2003 level.

Houtong is a small rural community; given the tendency of immigrant women to marry relatively low-status and economically marginal men in rural areas, it wouldn't be surprising if a disportionate number of wives there, like Sumarni, might be of foreign background. As this Wall Street Journal article on Taiwanese immigrant wives and their children points out, the village with the highest proportion of immigrant-mother children--17.5%--is Shihding, like Houtong a coal-mining village in rural Taipei County.

3. On a related note, the immigrant-wife phenomenon illustrates the diversity of the Taiwanese population. This diversity doesn't include only the Taiwanese aborigines who form 2% of the Taiwanese population, but the mainlander tenth of the Taiwanese population disproportionately concentrated in Taipei, along with the Min Nan/Fujianese-speaking Hoklo who form 70% of the Taiwanese population and the Hakka who form nearly a fifth of the population, alongside non-Chinese immigrants.

4. Incidentally, Houtong has become a tourism destination for tourists across greater China, i.e. China and Hong Kong and Macao as well as Taiwan. This may indicate the growing integration of Taiwan's population into the population of Greater China, as demonstrated not only by the Chinese immigrants to Taiwan but by the growing Taiwanese migrant population in mainland China, for instance the tens of thousands in Shanghai. China's not going to be the only reference point, as the Southeast Asia immigrants indicate, but it'll be quite important, arguably most important.

5. Finally, the demographics of the cat species are the dismal demographics that once afflicted the human species. Cats have a spectacularly high birth rate, bearing multiple litters with multiple kittens for most of their lives; female cats can actually become pregnant too early. Why, then are there not more cats out there? A terribly high death rate: indoor cats live for decades, outdoor cats for years. (Shakespeare's an indoor cat, if you're wondering.)

Thoughts?

Labels:

animals,

china,

fertility,

first nations,

immigration,

korea,

taiwan

Saturday, March 13, 2010

A few news links

Over the past couple of weeks, I've come across a lot of interesting population-related news links. Here they all are!

China Daily's Lin Shujuan writes about how a huge diaspora from Qingtian county (in eastern Zhejiang province) has, through settlement in western Europe, has helped make that newly wealthy county profoundly globalized.

IceNews reports on the heavy emigration from Greenland, especially among the young and educated of that island, that threatens the island's viability for independence. ]

At The Australian, Bernard Salt points out that Australia's recent trend towards a population in the 34 million range in a generation's time is quite recent and the discussion was triggered by a single document.

The New York Times writes about how growing demand for labour in migrant-sending areas of interior China is causing labour shortages in coastal China.

Last month, Polish radio reported that 25% of Poles in Iceland (almost all very recent immigrants) are unemployed, versus 9% of native Icelanders.

In 2009, Iceland Review reports that Iceland saw the net emigration of nearly five thousand people, most heading to other Nordic countries and a quarter to Poland.

Blic reports on how Serbia is trying to prevent brain drain to the West via spending on scientists' facilities and homes.

The Albanian Times writes about how Greece's economic crisis is hitting Albania by pushing Albanians migrants in Greece out of paid employment and possibly even back to an ill-prepared Albania.

South Korea's Chosun Ilbo reports on the continued low period fertility rate in South Korea, and the increasing tendency to postpone marriage and childbearing.

Switzerland is continuing to see strong population growth, driven mainly by immigration.

Labels:

australia,

china,

Council of Europe,

first nations,

gender,

korea,

norden

Tuesday, September 22, 2009

On the vulnerability of indigenous peoples to the H1N1 virus (and other diseases)

In Canada, the latest issue surrounding the H1N1 virus surrounds a rather spectacularly insensitive gaffe made by the ministry of health under the current Conservative minority government, which shipped body bags along with medical supplies to at least one Manitoba First Nations reserve. At the same time that this happened, however, significant outbreaks on First Nations reserves in British Columbia's Vancouver Island, while reports from around the world suggest that Indigenous Australians are also vulnerable and, indeed, some fear that indigenous peoples around the world could suffer a disproportionately high toll.

(Here, for brevity's sake, I'll go with Wikipedia's definition of indigenous peoples, as ethnocultural groups established on a particular territory before more recent states and migrants arrive. Here, I suppose that this definition can apply broadly for groups in areas as far separated as Siberia and Patagonia, the Northern Territory and Yukon.)

What's going on? It's a well-known fact that epidemic disease played a huge role in determining the future populations of indigenous peoples of the Americas as well as in also in Australia and the Maori, among other indigenous peoples. Epidemic diseases like measles and smallpox which entered populations entirely without immune defenses on account of their isolation from the Eurasian disease pool could easily inflict apocalyptic death tolls. To be considered, too, is the possibility that at least in the Americas the founder effect--the limited number of forebears--in the settlers of the Western Hemisphere may have produced a population lacking certain immune system-related genetic traits which could have at least hindered the spread of the disease. Finally, there's the effect of poverty: in Canada, at least, someone of First Nations background is much more likely to live in relative deprivation than a member of the general population, with lower incomes, higher unemployment, worse housing, and greater problems in accessing social capital. It might not be too far out of line to say that, for First Nations and other indigenous peoples elsewhere in the world, the flu in the 21st century might play something like the same iconic role as cholera in the 19th century or tuberculosis in the 20th, as a marker of the problems of urbanization and poverty.

I've a post stored up somewhere on my laptop describing how indigenous peoples are generally in an earlier stage of the demographic transition than the other citizens of the countries where they live, with substantially higher birth rates and cohort fertility. Sadly, it's also true that mortality among indigenous peoples is likewise quite a bit higher. Dispatching the body bags was rather insensitive, but some sort of in-depth planning to deal with this and other epidemic diseases here already and yet to come.

(Here, for brevity's sake, I'll go with Wikipedia's definition of indigenous peoples, as ethnocultural groups established on a particular territory before more recent states and migrants arrive. Here, I suppose that this definition can apply broadly for groups in areas as far separated as Siberia and Patagonia, the Northern Territory and Yukon.)

What's going on? It's a well-known fact that epidemic disease played a huge role in determining the future populations of indigenous peoples of the Americas as well as in also in Australia and the Maori, among other indigenous peoples. Epidemic diseases like measles and smallpox which entered populations entirely without immune defenses on account of their isolation from the Eurasian disease pool could easily inflict apocalyptic death tolls. To be considered, too, is the possibility that at least in the Americas the founder effect--the limited number of forebears--in the settlers of the Western Hemisphere may have produced a population lacking certain immune system-related genetic traits which could have at least hindered the spread of the disease. Finally, there's the effect of poverty: in Canada, at least, someone of First Nations background is much more likely to live in relative deprivation than a member of the general population, with lower incomes, higher unemployment, worse housing, and greater problems in accessing social capital. It might not be too far out of line to say that, for First Nations and other indigenous peoples elsewhere in the world, the flu in the 21st century might play something like the same iconic role as cholera in the 19th century or tuberculosis in the 20th, as a marker of the problems of urbanization and poverty.

I've a post stored up somewhere on my laptop describing how indigenous peoples are generally in an earlier stage of the demographic transition than the other citizens of the countries where they live, with substantially higher birth rates and cohort fertility. Sadly, it's also true that mortality among indigenous peoples is likewise quite a bit higher. Dispatching the body bags was rather insensitive, but some sort of in-depth planning to deal with this and other epidemic diseases here already and yet to come.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)