- Skepticism about immigration in many traditional receiving countries appeared. Frances Woolley at the Worthwhile Canadian Initiative took issue with the argument of Andray Domise after an EKOS poll, that Canadians would not know much about the nature of migration flows. The Conversation observed how the rise of Vox in Spain means that country’s language on immigration is set to change towards greater skepticism. Elsewhere, the SCMP called on South Korea, facing pronounced population aging and workforce shrinkages, to become more open to immigrants and minorities.

- Cities facing challenges were a recurring theme. This Irish Examiner article, part of a series, considers how the Republic of Ireland’s second city of Cork can best break free from the dominance of Dublin to develop its own potential. Also on Ireland, the NYR Daily looked at how Brexit and a hardened border will hit the Northern Ireland city of Derry, with its Catholic majority and its location neighbouring the Republic. CityLab reported on black migration patterns in different American cities, noting gains in the South, is fascinating. As for the threat of Donald Trump to send undocumented immigrants to sanctuary cities in the United States has widely noted., at least one observer noted that sending undocumented immigrants to cities where they could connect with fellow diasporids and build secure lives might actually be a good solution.

- Declining rural settlements featured, too. The Guardian reported from the Castilian town of Sayatón, a disappearing town that has become a symbol of depopulating rural Spain. Global News, similarly, noted that the loss by the small Nova Scotia community of Blacks Harbour of its only grocery store presaged perhaps a future of decline. VICE, meanwhile, reported on the very relevant story about how resettled refugees helped revive the Italian town of Sutera, on the island of Sicily. (The Guardian, to its credit, mentioned how immigration played a role in keeping up numbers in Sayatón, though the second generation did not stay.)

- The position of Francophone minorities in Canada, meanwhile, also popped up at me.

- This TVO article about the forces facing the École secondaire Confédération in the southern Ontario city of Welland is a fascinating study of minority dynamics. A brief article touches on efforts in the Franco-Manitoban community of Winnipeg to provide temporary shelter for new Francophone immigrants. CBC reported, meanwhile, that Francophones in New Brunswick continue to face pressure, with their numbers despite overall population growth and with Francophones being much more likely to be bilingual than Anglophones. This last fact is a particularly notable issue inasmuch as New Brunswick's Francophones constitute the second-largest Francophone community outside of Québec, and have traditionally been more resistant to language shift and assimilation than the more numerous Franco-Ontarians.

- The Eurasia-focused links blog Window on Eurasia pointed to some issues. It considered if the new Russian policy of handing out passports to residents of the Donbas republics is related to a policy of trying to bolster the population of Russia, whether fictively or actually. (I'm skeptical there will be much change, myself: There has already been quite a lot of emigration from the Donbas republics to various destinations, and I suspect that more would see the sort of wholesale migration of entire families, even communities, that would add to Russian numbers but not necessarily alter population pyramids.) Migration within Russia was also touched upon, whether on in an attempt to explain the sharp drop in the ethnic Russian population of Tuva in the 1990s or in the argument of one Muslim community leader in the northern boomtown of Norilsk that a quarter of that city's population is of Muslim background.

- Eurasian concerns also featured. The Russian Demographics Blog observed, correctly, that one reason why Ukrainians are more prone to emigration to Europe and points beyond than Russians is that Ukraine has long been included, in whole or in part, in various European states. As well, Marginal Revolution linked to a paper that examines the positions of Jews in the economies of eastern Europe as a “rural service minority”, and observed the substantial demographic shifts occurring in Kazakhstan since independence, with Kazakh majorities appearing throughout the country.

- JSTOR Daily considered if, between the drop in fertility that developing China was likely to undergo anyway and the continuing resentments of the Chinese, the one-child policy was worth it. I'm inclined to say no, based not least on the evidence of the rapid fall in East Asian fertility outside of China.

- What will Britons living in the EU-27 do, faced with Brexit? Bloomberg noted the challenge of British immigrant workers in Luxembourg faced with Brexit, as Politico Europe did their counterparts living in Brussels.

- Finally, at the Inter Press Service, A.D. Mackenzie wrote about an interesting exhibit at the Musée de l’histoire de l’immigration in Paris on the contributions made by immigrants to popular music in Britain and France from the 1960s to the 1980s.

Showing posts with label united kingdom. Show all posts

Showing posts with label united kingdom. Show all posts

Saturday, May 04, 2019

Some links: immigration, cities, small towns, French Canada, Eurasia, China, Brexit, music

Another links post!

Labels:

china,

cities,

demographics,

european union,

french canada,

links,

migration,

popular culture,

russia,

ukraine,

united kingdom

Wednesday, February 20, 2019

Some news links: public art, history, marriage, diaspora, assimilation

Some more population-related links popped up over the past week.

- CBC Toronto reported on this year’s iteration of Winter Stations. A public art festival held on the Lake Ontario shorefront in the east-end Toronto neighbourhood of The Beaches, Winter Stations this year will be based around the theme of migration.

- JSTOR Daily noted how the interracial marriages of serving members of the US military led to the liberalization of immigration law in the United States in the 1960s. With hundreds of thousands of interracial marriages of serving members of the American military to Asian women, there was simply no domestic constituency in the United States

- Ozy reported on how Dayton, Ohio, has managed to thrive in integrating its immigrant populations.

- Amro Ali, writing at Open Democracy, makes a case for the emergence of Berlin as a capital for Arab exiles fleeing the Middle East and North America in the aftermath of the failure of the Arab revolutions. The analogy he strikes to Paris in the 1970s, a city that offered similar shelter to Latin American refugees at that time, resonates.

- Alex Boyd at The Island Review details, with prose and photos, his visit to the isolated islands of St. Kilda, inhabited from prehistoric times but abandoned in 1930.

- VICE looks at the plight of people who, as convicted criminals, were deported to the Tonga where they held citizenship. How do they live in a homeland they may have no experience of? The relative lack of opportunity in Tonga that drove their family's earlier migration in the first place is a major challenge.

- Window on Eurasia notes how, in many post-Soviet countries including the Baltic States and Ukraine, ethnic Russians are assimilating into local majority ethnic groups. (The examples of the industrial Donbas and Crimea, I would suggest, are exceptional. In the case of the Donbas, 2014 might well have been the latest point at which a pro-Russian separatist movement was possible.)

Labels:

assimilation,

diaspora,

estonia,

germany,

islands,

latvia,

links,

marriage,

middle east,

migration,

popular culture,

racism,

russia,

scotland,

south pacific,

toronto,

ukraine,

united kingdom,

united states

Sunday, January 27, 2019

Some links from the blogosphere

As a prelude to more substantial posting, I thought I would share with readers some demographics-related links from my readings in the blogosphere.

- The blog Far Outliers, concentrating on the author's readings, has been looking at China in recent weeks. Migrations have featured prominently, whether in exploring the history of Russian migration to the Chinese northeast, looking at the Korean enclave of Yanbian that is now a source and destination for migrants, and looking at how Tai-speakers in Yunnan maintain links with Southeast Asia through religion. The history of Chinese migration within China also needs to be understood.

- Lawyers, Guns and Money was quite right to argue that much of the responsibility for Central Americans' migration to the United States has to be laid at the foot of an American foreign policy that has caused great harm to Central America. Aaron Bastani at the London Review of Books' Blog makes similar arguments regarding emigration from Iran under sanctions.

- Marginal Revolution has touched on demographics, looking at the possibility for further fertility decline in the United States and noting how the very variable definitions of urbanization in different states of India as well as nationally can understate urbanization badly.

Labels:

central america,

china,

fertility,

india,

iran,

korea,

links,

migration,

russia,

siberia,

southeast asia,

statistics,

united kingdom,

united states

Thursday, October 06, 2016

On the new official xenophobia in the United Kingdom

Brexit is something that I've been paying attention to this year. In March, I pointed out that the limited free movement with other Commonwealth countries that some Brexit proponents was offering. (The curious fact that this free movement would be only with rich and white countries is something I noted in passing.) In June, meanwhile, I noted the losses that the United Kingdom would suffer and linked to Zakc Beauchamps' Vox piece noting that, to the considerable extent that migration concerns did impact Brexit, they were at best exaggerated and at worst inaccurate.

Yesterday, my Facebook feed was filled by reactions to an astonishing Financial Times report. I had hoped the reports of Amber Rudd's statements about forcing companies to disclose their foreign workforces were inaccurate, but, alas, no. The Guardian, for one, confirmed this.

Theresa May’s government is facing a growing backlash over a proposal to force companies to disclose how many foreign workers they employ, with business leaders describing it as divisive and damaging.

The proposal was revealed by Amber Rudd, the home secretary, at the Conservative party conference on Tuesday as a key plank of a government drive to reduce net migration and encourage businesses to hire British staff.

However, senior figures in the business world warned the plan would be a “complete anathema” to responsible employers and would damage the UK economy because foreign workers were hired to fill gaps in skills that British staff could not provide. One chief executive of a FTSE 100 company, whose workforce includes thousands of EU citizens, said it was “bizarre”.

The proposals, which are subject to consultation, have also been questioned from within the Conservative party. Lord Finkelstein, the Tory peer, told the BBC it was a “misstep”, while Tory MP Neil Carmichael, chairman of the House of Commons education select committee, said the policy was “unsettling” and would “drive people, business and compassion out of British society and should not be pursued any further”.

[. . .]

Rudd was forced to defend the proposals on Wednesday, insisting they were not xenophobic and that she had been careful about the language used. The home secretary told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme that some companies were “getting away” with not training British workers and “we should be able to have a conversation about what skills we want to have in the UK”.

That, as the Independent reported, this proposal is apparently quite popular with the general British public is another point.

It seems clear that the United Kingdom is heading for a hard Brexit, regardless of the poor economic rationale for this. It also seems clear that this will hit Britain's immigrant populations and ethnic minorities badly. In the case of the relatively recent European Union migrants from Poland and elsewhere, this might even trigger return migrations, to their homelands or elsewhere. I'm reminded of how France's Polish immigrant community first began to grow sharply in the 1920s following the displacement of ethnic Polish workers from the German Ruhr. Will Germany end up the main beneficiary of post-2004 Polish migrants, as I speculated it might have had 2004 gone differently?

The biggest lesson to take from Brexit is this: Whatever else it was about, Brexit was not about opening up the UK to the wider world. This is made clear by the aftermath, still unfolding. If the British government is to adopt a policy of naming and shaming companies which employ foreign workers, with even Irish migrants possibly coming under the aegis of these regulations, it's laughable to say that the United Kingdom is going to globalize.

Maria Farrell's mournful post at Crooked Timber, recapitulating Stefan Zweig's mourning for the open borders of pre-First World War Europe, is entirely appropriate. These losses are terribly sad, and so avoidable if only Britain had more leaders who cared about their country's future.

Labels:

european union,

germany,

ireland,

migration,

poland,

united kingdom

Monday, June 27, 2016

"Brexit was fueled by irrational xenophobia, not real economic grievances"

Vox's Zack Beauchamp has a great extended article, "Brexit was fueled by irrational xenophobia, not real economic grievances", that takes a look at how migration concerns helped create a pro-Brexit majority. Critically, as far as he can prove, these seem not to have been based on actual issues, but rather on perceptions.

The surge [of immigrants] was a result (in part but not in whole) of EU rules allowing citizens of of EU countries to move and work freely in any other EU member country.

Pro-Leave campaigners, and sympathetic observers in the media, argued that this produced a reasonable skepticism of immigration’s effect on the economy — and Brexit was the result.

"The force that turned Britain away from the European Union was the greatest mass migration since perhaps the Anglo-Saxon invasion," Atlantic editor David Frum writes. "Migration stresses schools, hospitals, and above all, housing."

Yet there’s a problem with that theory: British hostility to immigrants long proceeds the recent spate of mass immigration.

Take a look at this chart, from University of Oxford’s Scott Blinder. Blinder put together historical data on one polling question — the percent of Brits saying there were too many immigrants in their country. It turns people believed this for decades before mass migration even began[.]

A worthwhile read, if a depressing one.

A worthwhile read, if a depressing one.

Labels:

demographics,

european union,

links,

migration,

politics,

united kingdom

Saturday, June 25, 2016

Some demographic perspectives on Brexit and the future United Kingdom

I've been spending today taking in the fact that the vote in the British referendum on European Union membership went in favour of the Leave camp. There's certainly going to be repercussions in Canada, with Torontoist noting the impact on Toronto-based businesses of British instability, the Toronto Star observing that the United Kingdom has become a less attractive platform for European business, and the CBC observing that British departure jeopardizes a Canadian-European Union free trade agreement that has taken seven years to bring to the point of completion. (Brexit proponents hoping for a quick deal should take note.)

The first important thing that needs to be said about Brexit, at least from a perspective relative to population, is that the desire of Brexit proponents to somehow come up with a new relationship with the European Union that will keep the single EU market as before while keeping out EU migrants looks impossible. The freedom of movement of workers is one of the foundational "four freedoms" of post-war European integration, one of the elements of this internal single market, and it's very difficult for me to imagine a circumstance in which a seceding member-state would be allowed to pick and choose what elements of its old membership it could keep. What would be the incentive for any polity to give that prerogative to a seceding member-state? The proposals of Québécois and Scottish sovereigntists for continued integration with their parent states, on the terms of the separatist entities and only in the areas they wanted (only, I would add, in the areas that people were unsure the separatists could handle like monetary policy) come to mind.

Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein do belong to the European Economic Area, often mentioned, but they have no ability to pick and choose. Switzerland is not a formal member of the EEA but it comes quite close, with a tailored package of treaties which provides it with access to the single market. Switzerland's decision two years ago to limit free migration following a 2014 immigration referendum has triggered a continuing crisis with the European Union still far from being solved. Britain's negotiating partners in the European Union may well be willing to accept EEA membership, but I would be surprised if free movement of people would be sacrificed. Yet if that did not happen, how can a post-Brexit government drawing its support substantially from anti-immigrant sentiment accept such a deal? There will be economic shocks ahead.

It can't be doubted that immigration, perhaps most recently the Middle Eastern refugee crisis but also post-2004 immigration from central Europe, helped trigger Brexit, as noted by Migration Information.

The topic of migration has been central to the referendum debate. For an astonishing nine consecutive months, voters have identified immigration as among the most important issues facing Britain (based on Ipsos MORI polling). In April, 47 percent rated immigration as the most pressing concern; just half that number identified the economy as the most important issue. However, when asked specifically about their vote on Europe, respondents cite the economy as their primary consideration, with migration a close second.

The public debate on migration has encompassed several dimensions, including whether being part of the European Union enhances or decreases security; what the United Kingdom’s response should be on accepting refugees for resettlement and providing additional funds to help resolve the refugee crisis; and above all what migration flows will look like in the future and whether restrictions on migration are compatible with Brexit (and the resultantly-necessary new EU trade deal). The underlying theme is to what degree and at what cost the national government can control and restrict migration by leaving the European Union.

Not surprisingly after the Paris and Brussels attacks, both sides share a general concern over terrorism and security related to migration. Remain campaigners claim improved intelligence sharing between EU countries will increase security, while Leave proponents argue that the United Kingdom’s greater ability to prevent movement once outside the European Union and increased border security will reduce threats.

With EU Member States having received more than 1 million asylum seekers and migrants in 2015, both sides contend the crisis will dramatically influence voting decisions. The United Kingdom has played a highly limited role in the refugee crisis thus far (refusing for example to take part in the EU scheme to relocate 160,000 refugees across Member States). Coupled with relatively low numbers of spontaneous arrivals of refugees and the absence thus far of a terrorist attack on UK soil, suggestions that terrorism and Europe’s refugee crisis will decide the referendum appear exaggerated.

Public opinion on future migration flows and restrictions currently matter more to voters. The most passionate Leave supporters (representing around one-quarter of the UK public) are very strongly correlated with the most anti-immigrant UK voters. Voters strongly attached to an “English” (as opposed to a “British”) identity—a disproportionately Conservative-leaning group crucial to the outcome—favor leaving the European Union. Furthermore, anxieties over migration extend beyond this group, with two-thirds of the public favoring migration restrictions.

I'll quote at length from the introduction to Open Europe's April 2016 study "Where next? A liberal, free-market guide to Brexit". Migration, the authors suggest, is not likely to fall even in the case of Brexit.

Immigration

a) While there would be political pressure to reduce immigration following Brexit, there are several reasons why we believe headline net immigration is unlikely to reduce much:

The business case for maintaining a flexible supply of labour. The evidence suggests that, with a record high employment rate, the UK’s labour market is already tightening;

the political and economic challenge of finding policy alternatives to relieve pressure on the public finances caused by ageing demographics, where immigration can help smoothen the path to fiscal sustainability;

the effects of globalisation on migration flows, which the UK is not alone in experiencing;

and the likelihood of some constraints on UK immigration policy under a new arrangement with the EU.

b) Nevertheless, free from EU rules on free movement, the UK would likely pursue a selective policy more geared towards attracting skilled migration, which could be more politically acceptable.

c) Open Europe would recommend a system seeking to emulate the points-based systems of Canada and Australia. The system could be weighted strongly towards those with a job offer, but also offer a route for skilled migrants seeking work. Such a system could give priority to UK industries and employers suffering skills shortages but also allow a flexible supply of skilled workers to enter the UK labour force subject to a cap which could be varied depending on economic circumstances. However, there is likely to be a continued need for migrant labour to fill low-skilled jobs. Therefore, the UK would also need a mechanism to fill low-skilled jobs or meet labour shortages where employers have recently relied on EU migrants.

d) However, there is likely to be a trade-off between the depth of any new economic agreement with the EU and the extent to which the UK will have to accept EU free movement. The evidence from the precedents of Norway and Switzerland suggest that the deeper the agreement, the more likely the UK will need to accept free movement. This might mean building in preferential treatment for EU citizens in the UK’s new points system, which would give EU nationals priority over non-EU nationals, or it could create a separate temporary migration scheme for migrants from the EU.

e) The UK is far from alone in its migration experience in terms of developed economies. Between 2000 and 2015 the UK received 3.7 migrants for every thousand people, which puts it just above the average but below countries such as Canada, Australia, Norway and Switzerland. If the UK had experienced the same level of immigration as Canada or Australia there would have been an additional 3 million or 4.4 million migrants respectively coming to the UK over the past decade – though of course the UK is a more crowded country.

A points system, as The Independent has argued, might well lead to more immigrant admissions. I've observed here, at least as far back at 2012, that British anti-immigrant sentiment is general. Whether European Union, Commonwealth, or other, immigrants just aren't welcome.

A post-Brexit United Kingdom will become less attractive for migrants. It may, between hostile policies and a worsening economy, become much less attractive. I feel justified in discounting scenarios where Britain will become more attractive, more open to immigrants. If the resulting shortfalls in labour last, this may well lower the United Kingdom's long-term potential for economic growth. What a waste of potential!

Who knows? If things get bad enough, we might even see emigration on a substantial scale. CBC reported that the number of Britons googling how to move to Canada after the referendum results has sparked sharply. I would not at all bet against seeing here in Toronto a wave of British immigrants not at all unlike the Irish immigrants who came just a few years ago.

(For further reading, I recommend the Brexit site of the Migration Observatory.)

Labels:

demographics,

european union,

labour market,

politics,

united kingdom

Wednesday, May 04, 2016

On speculating about the effects of German labour market restrictions in 2004

In February 2013, in noting the arguments of Jonathan Last about migration, I noted that policy on migration--in sending countries and in receiving countries--was important in directing flows. The example I used was that of post-2004 Polish migration to the United Kingdom.

Consider the movement of Poles to Germany. Large-scale Polish migration west dates back to the beginning of the Ostflucht, the migration of Germans and Poles from what was once eastern Germany to points west, in around 1850. By the time Poland regained its independence in 1919, hundreds of thousands of Poles lived in Germany, mainly in the Ruhr area and Berlin. Leaving aside the exceptional circumstances of the post-Second World War deportations of Germans from east of the Oder-Neisse line, Polish migration to (West) Germany continued under Communism, as hundreds of thousands of people with German connections--ethnic Germans, members of Germanized Slavic populations, and Polish family members--emigrated for ethnic and economic reasons. In the decade of the 1980s, up to 1.3 million Poles left the country, the largest share heading for Germany. Large-scale Polish migration to Germany has a long history.

And yet, in the past decade, by far the biggest migration of Poles within the European Union was directed not to neighbouring Germany but to a United Kingdom that traditionally hasn't been a destination. Most Polish migration to Germany, it seems, is likely to be circular migration; Germany missed out on a wave of immigrants who would have helped the country's demographics significantly. Why? Germany chose to keep its labour markets closed for seven years after Poland's European Union admission in 2004, while the United Kingdom did not, the results being (among other things) that Polish is the second language of England.

This was a huge surge. In their November 2014 discussion paper "Polish Emigration to the UK after 2004; Why Did So Many Come?" (PDF format), Marek Okolski and John Salt noted that the Polish migration post-2004 dramatically reversed a trend one half-century old of decline.

A Polish presence in the UK population existed before 2004 which helped to create networks and contacts between the diaspora and those back home. The 1951 UK census recorded 152 000 people born in Poland, a hangover from the Second World War after which many preferred to relocate to or stay in the UK rather than return home. By 1981 the number had shrunk to 88 000 and although unrest and Martial Law in Poland continued a trickle of new migrants into the UK, the inevitable ageing of the post-war group took its toll so that by 2001 the number had fallen to 58 000. The next decade, however, saw an increase in the number of Polish born in the UK to 676,000 in 2011.

The authors conclude that this surge had much to do with a perfect storm of coincidence, of transformations in Poland and the United Kingdom alike aided by a new transnationalism.

Let us begin with the “right people”. The concept of “right people” embraces the surplus (reinforced by the “boom” of young labour market entrants/higher school graduates) and structural mismatches of labour in Poland, post-communist anomy (migration as one viable strategies to overcome that, similar to migration as a response to social disorder accompanying rapid urbanization, as described by Thomas and Znaniecki), high educational and cultural competence/maturity (including widespread knowledge of the English language) and awareness of freedoms and entitlements stemming from “European citizenship”. Furthermore, at least since 1939 Poles had been generally favourably regarded by the British.

The “right place” was the UK labour market, although it was not immediately apparent at the time. The economy was growing rapidly but there was a reluctance among domestic workers to undertake many of the jobs available at the wage rates on offer. Migrant workers willing to work for minimum (or less) wages allowed employers to avoid capital investment that would have increased productivity in, for example, food processing. In service provision, such as hospitality, migrants provided flexibility in working practices that reduced costs. Furthermore, the UK’s flexible labour market made it easy for those Poles with skills and initiative to engage in upward occupational mobility and encouraged them to stay. In addition, public attitudes towards the inflow of people from new EU member states were generally favourable. Coincidental with this was the “compression” of the physical distance between Poland and the UK through a rapid development of non-costly and effective transport, communication and information facilities between the two countries. This made it possible to achieve the high levels of flexibility required by both employers and migrants.

Finally, by the “right circumstances” we mean the juncture of Poland’s accession to the EU with the decision taken by the UK government to grant immediate access to the British labour market. That other countries did not follow suit meant the lack of any strong competition from other receiving countries.

Plausibly, similar factors may have operated in connection to immigration from the Baltic States, specifically of Lithuanians and Latvians. (Estonians seem not to have been nearly so likely to emigrate, at least not to the United Kingdom.

Germany eventually did open its labour markets to migrants from the new European Union member-states, but the effect was limited.

Germany had 580,000 A8 nationals at the end of 2009, including 419,000 Poles (the UK had 550,000 Poles at the end of 2009). In Germany, almost a third of women from A8 countries are employed in health and caring professions, while a third of A8 male migrants in Germany are employed in manufacturing and construction.

The consensus estimate is that another 140,000 A8 nationals a year may now move to Germany, doubling the stock of A8 nationals in Germany to 1.3 million by 2020, this despite the fact that wages have risen in Eastern Europe over the past decade. Average wages of E5 an hour in Poland are expected to reduce incentives to migrate to Germany, where many A8 nationals earn E8 to E10 an hour. However, German unions expressed fears that more A8 migrants may slow wage increases.

Okolski and Salt point out that, overall, Polish migrants to Germany tended to be older and have lower levels of human capital than Polish migrants to the United Kingdom, limiting their potential contributions. In their January 2013 paper "10 Years After: EU Enlargement, Closed Borders, and Migration to Germany" (PDF format), Benjamin Elsner and Klaus F. Zimmermann conclude that Germany missed out by opting to limit access to its labour markets.

The extent to which immigration affects wages and employment depends on the degree of substitutability between migrants and natives. The more substitutable migrants and natives are, the stronger is the effect. Recent studies by D'Amuri et al. (2010) and Brücker & Jahn (2011) have shown that Germans and immigrants with the same education and work experience are indeed imperfect substitutes. Hence, immigration should only have a moderate effect on wages and employment of natives. Based on this line of argumentation, and in view of the many young and well-educated migrants that went to the UK and not to Germany, we conclude that Germany missed a chance by not opening up its borders in 2004. The fear of the German government that thousands of low-skilled workers would emigrate from the NMS turned out not to be true. Instead, EU8 migrants were actually better-educated than the average native. As shown in previous work by Brenke et al. (2009), immigrants from the EU8 countries mostly competed with previous immigrants and not with natives. For Germany as a whole, the costs of the restrictions exceeded the benefits by far.

Imagine, if you would, that Germany had joined the United Kingdom in 2004 in giving migrants from the new European Union member-states central and eastern Europe. It's certainly imaginable that Germany would have shared in the surge, perhaps even that given its long history as a destination for migrants from Poland and points beyond it would have stayed ahead of the United Kingdom as a destination. Plausibly, this new altered immigration flow would have provided a net benefit for Germany, while still providing some (if fewer) benefits for a United Kingdom that was not such a natural destination. Everyone would have benefited economically.

Another consequence might have been weaker support for Euroskepticism in the United Kingdom. For a variety of reasons which I don't quite understand, this post-2004 migration to the United Kingdom has been exceptionally politically controversial, to the point of strongly accentuating Euroskepticism and even support for Britain's exit from the European Union. There was going to be a surge of migration from the poorer European Union member-states to the richer ones, but if it was not so overwhelmingly focused on a single (if large) state as a destination, would it have had less of an effect? I wonder if this thinking has anything to do with current European Union policy, for instance in trying to avoid the concentration of refugees in a particular member-state and to spread them out.

Labels:

alternate history,

european union,

germany,

latvia,

lithuania,

migration,

united kingdom

Monday, March 14, 2016

Some followups

For tonight's post, I thought I'd share a few news links revisiting old stories

- The Guardian notes that British citizens of more, or less, recent Irish ancestry are looking for Irish passports so as to retain access to the European Union in the case of Brexit. (Net migration to the United Kingdom is up and quite strong, while Cameron's crackdown on non-EU migrants has led to labour shortages.

- NPR notes one strategy to get fathers to take parental leave: Have them see other fathers take it.

- Reuters notes that the hinterland of Fukushima, depopulated by natural and nuclear disaster, seems set to have been permanently depopulated. Tohoku

- Bloomberg noted that East Asia's populations are aging rapidly, another article noting how Japan's demographic dynamics are setting a pattern for other high-income East Asian economies.

- In Malaysia, the Star notes that low population growth among Malaysian Chinese will lead to a sharp fall in the Chinese proportion in the Malaysian population by 2040.

- Coming to Alberta, CBC notes how the municipality of Fort McMurray has been hit very hard by the end of the oil boom, as has been Alberta's largest city and business centre of Calgary.

- On the subject of North Korea and China, The Guardian wrote about the stateless children born to North Korean women in China, lacking either Chinese or North Korean citizenship.

- The Inter Press Service notes that, as the Dominican Republic cracks down on Haitian migrants and people of Haitian background generally, women are in a particular situation.

- IWPR provides updates on Georgia's continuing and ongoing rate of population shrinkage, a consequence of emigration.

- On the subject of Cuba, the Inter Press Service reported on Cuban migrants to the United States stranded in Latin America, while Agence France-Presse looked at the plight of Cuba's growing cohort of elderly.

Labels:

ageing,

alberta,

china,

cuba,

demographics,

east asia,

ethnicity,

european union,

fertility,

georgia,

haiti,

ireland,

japan,

korea,

latin america,

malaysia,

migration,

united kingdom,

united states

Wednesday, March 02, 2016

On Brexit and how limited free movement in the Commonwealth is a poor substitute for the EU

A couple of weeks ago at my blog, A Bit More Detail, I linked to an interesting article about the legacies of the First World War and the thin ties of the Commonwealth at The Conversation. There, James McConnel and Peter Stanley describe how a British-Australian dispute over commemorating a battle of the First World War, the Battle of Fromelles, brings our contemporary nationalisms into conflict with the imperial-era reality of a much closer and more complex British-Australian relationship of a century ago. There was no clear division between Briton and Australian.

Awareness of the historical context of the battle has clearly informed some British coverage of the decision by the Australian Department for Veterans Affairs to invite only the families of Australians to the memorial ceremony this year. Coverage in the UK has suggested that “banning” the relatives of the 1,547 British casualties of Fromelles, exclusively focuses on the Australian soldiers lost in light of the smaller, but still significant, British casualties.

In response, an Australian spokesman noted in The Times (paywall) that Britain’s own Somme commemoration of July 1 2016 will only be open to British citizens. It’s clear the war’s centenary is being shaped by modern national and state agendas.

But there is an anachronism at the very heart of this spat because – as the military historian Andrew Robertshaw said: “A surprisingly high proportion of the Australian Imperial Force were not actually born in Australia.”

Many of the Australian volunteers, the authors go on to explain, were themselves recent migrants from the United Kingdom, still feeling many loyalties to the country of their birth. At a time when the nationhood of Australia--arguably, like that of the other settler colonies of the British Empire--was far from established and issues of citizenship and identity were uncontestedly unsettled.

Among the names included under the headline “Australian casualties” in The (Melbourne) Argus of August 22 1916 was that of Private Charles Herbert Minter. He was just one of 5,513 soldiers of the AIF who had been killed, wounded, or captured during the bloody attack on Fromelles of July 1916.

Minter was born in Dover, in the English county of Kent, in 1888. He arrived in Australia in October 1910 at the age of 22 and enlisted less than five years later in the Australian Imperial Force in July 1915. In doing so, he was typical of many of the so-called “new chums” (as recent arrivals from Britain were colloquially called). One estimate suggests that 27% of the first AIF contingent were British born, with estimates for the war as a whole varying between 18% and 23%.

Australia was hardly unusual among the Dominions in this respect – 26% of the first contingent of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force were British born, while 64% of the first contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force had been born in Britain. As one of these men commented years afterwards: “I felt I had to go back to England. I was an Englishman, and I thought they might need me.”

That Minter’s British descendants (his “sorrowing sister” posted a death notice in tribute to her “dear brother” in the Dover Express in August 1916) would not technically be eligible to attend the Fromelles commemoration highlights the way that the multi-layered identities of these British-born “diggers” (and “Kiwis”, and “Canucks”) have been rendered one-dimensional in the century since the guns fell silent.

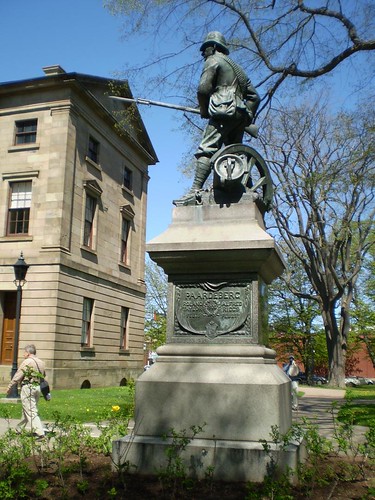

My own personal background, and that of my native province of Prince Edward Island, is not nearly as closely tied to the United Kingdom. The last of my ancestors arrived on the far side of the Atlantic Ocean from Europe in the 1850s. The legacies of the British Empire, of the blood shared in common ancestry and spilled in wars, are still ubiquitous. Never mind the matter of ancestry, of Canada's domination by descendants of migrants from the British Isles, never mind even the great cenotaphs to the dead in the world wars. In Charlottetown, just around the corner from the provincial legislature and in front of the courts, stands a monument to the now forgotten Boer War battle of Paardeberg, waged in 1900. Only after I took a photo of this monument in 2008 did I learn about this battle, once so important to Prince Edward Islanders as to deserve a prominent memorial.

It's still up in 2014.

The British Empire was a reality. It is no longer. In the case of Canada, the repatriation of the Canadian constitution that was completed in 1982 definitely established Canada as a state fully independent from the United Kingdom. All of the other erstwhile colonies, whether destinations for British migrants or not, have gone through similar processes. The Commonwealth of Nations has some meaning, particularly inasmuch as our head of state is shared with more than a dozen other countries and as the organization that gives its name to a sporting event of some note, but that's it.

There are some who would like to change this, who would like to establish unfettered freedom of movement between at least some of the Commonwealth realms. In recent years, it has been the subject of some discussion, talked about in March 2015 at Marginal Revolution, and reported by Yahoo in November 2014.

Canadians who want to live or travel in the United Kingdom could be granted the ability to do so without the current shackles of visa requirements and limitations, should the British parliament heed the call of a British think-tank.

That call involves urging for the creation of a vast “bilateral mobility zone” that would give citizens of the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and Canada the ability to travel freely, without the need for work or travel visas, between those Commonwealth nations.

"We want to add distinct value to Commonwealth citizenship for those who wish to visit, work or study in the U.K.," reads the report released by the Commonwealth Exchange. "The Commonwealth matters to the U.K. because it represents not just the nation’s past but also its legacy in the present, and its expanded potential in the U.K.’s future."

The idea of easier mobility between Canada and some of its closest Commonwealth allies would be an exciting concept. There are currently 90,000 Canadian-born residents of the U.K., and another 34,000 living in Australia and New Zealand.

The Commonwealth Exchange report takes on the larger question of the U.K.’s place on the international stage, noting that while the economies of European Union members are struggling, the Commonwealth nations such as Australia and India are booming. Despite this, its connection to those countries is weakening.

This is an unlikely outcome. As the CBC noted in its reportage, there just is too much that is vague about the proposal, and from the Canadian perspective not enough to gain.

“I think it’s an intriguing proposal, but I think chances are it will be some years in the making if it’s ever to be realized,” said Emily Gilbert, an associate professor who teaches Canadian studies and geography at the University of Toronto.

“So I don’t know where the political will would be coming from to get this going.”

Gilbert said allowing greater mobility is a worthy goal, but much depends on the specifics of the agreement between the countries.

Would immigrants automatically gain permanent resident status or have full access to citizenship rights, for example, beyond simply having the right to work and stay indefinitely?

“If they were to move ahead with this, that is what would be worked out, and the devil is in the details,” she said.

Jeffrey Reitz, from the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs, said the chance of seeing such an “eccentric” agreement between the four countries is effectively zero.

He said it’s unclear why Canada would pursue a proposal with New Zealand, Australia and U.K. instead of the U.S. and Mexico, countries that are already part of a free trade agreement. Or why not a proposal to loosen travel between all 53 Commonwealth countries?

The Commonwealth Freedom of Movement Association ranks highly on Google. In its blog, one author argues that expanding this four-country zone to include other candidates--like Jamaica, an Anglophone island nation not much different from New Zealand in size, or a South Africa that has as large a natively Anglophone population--would create the risk of too much migration. In all honesty, with the exception of the noteworthy migration of New Zealanders to Australia, I'm not sure that there are any especially significant ongoing flows of migrants between these four Commonwealth realms. Is there much of an untapped potential for migration? All four countries are already high-income countries with comparable standards of living. Is there any particular point to this?

There actually is, but it is not related to gains from migration. With this, we come back to what I talked about here in July 2012, about the idea of liberalized migration between certain Commonwealth realms serving as a supposed substitute for Britain's participation in the European Union's unified labour market. The idea of a Canadian migrant to some Britons would be substantially more appealing than the idea of a Polish migrants, partly because of the assumption of shared ancestry but also because such might be the first step towards Britain's ascent to non-European prominence. Nick Pearce's essay "After Brexit: the Eurosceptic vision of an Anglosphere future", published last month at Open Democracy, sets the stage for the Anglospheric dreams of many in the United Kingdom.

In the last couple of decades, eurosceptics have developed the idea that Britain’s future lies with a group of “Anglosphere” countries, not with a union of European states. At the core of this Anglosphere are the “five eyes” countries (so-called because of intelligence cooperation) of the UK, USA, Australia, Canada and New Zealand. Each, it is argued, share a common history, language and political culture: liberal, protestant, free market, democratic and English-speaking. Sometimes the net is cast wider, to encompass Commonwealth countries and former British colonies, such as India, Singapore and Hong Kong. But the emotional and political heart of the project resides in the five eyes nations.

[. . .]

As Professor Michael Kenny and I set out in an essay for the New Statesman, the Anglosphere returned as a central concept in eurosceptic thinking in the 1980s, when Europhilia started to wane in the Conservative Party and Thatcherism was its ascendancy. On the right of the Conservative Party, we argued:

“…American ideas were a major influence, especially following the emergence of a powerful set of foundations, think tanks and intellectuals in the UK that propounded arguments and ideas that were associated with the fledgling “New Right”. In this climate, the Anglosphere came back to life as an alternative ambition, advanced by a powerful alliance of global media moguls (Conrad Black, in particular), outspoken politicians, well-known commentators and intellectual outriders, who all shared an insurgent ideological agenda and a strong sense of disgruntlement with the direction and character of mainstream conservatism.

[. . .]

The idea of the Anglosphere as an alternative to the European Union gained ground amongst conservatives in their New Labour wildnerness years, when transatlantic dialogue and trips down under kept their hopes of ideological revival alive. It was given further oxygen by the neo-conservative coalition of the willing stitched together for the invasion of Iraq, which seemed to demonstrate the Anglosphere’s potency as an geo-political organizing ideal, in contrast to mainstream hostility to the war in Europe. By the time of the 2010 election, the Anglosphere had become common currency in conservative circles, name checked by leading centre-right thinkers like David Willetts, as well as eurosceptic luminaries, such as Dan Hannan MEP, who devoted a book and numerous blogs to the subject.

As Foreign Secretary, William Hague, sought to strengthen ties between the Anglosphere countries, despite the indifference shown by the Obama presidency to the idea. After leaving the cabinet, the leading eurosceptic Owen Patterson gave a lengthy speech in the US on the subject of an Anglospheric global alliance for free trade and security; he could expect a sympathetic hearing in Republican circles, if not the White House. And in its 2015 election Manifesto, UKIP praised the Anglosphere as a “global community” of which the UK was a key part.

I'll note now, just as I did four years ago, that all this is terribly unlikely, at least in Canada. I am personally unaware of any significant political group that would sign on to this particular structure. The Commonwealth unification movement is dead. Canada is an independent state with its own interests, many of which do not follow the patterns of pro-Brexit Anglospherists. Indeed, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has stated Canada's preference for a United Kingdom that remains engaged within the European Union. The United Kingdom could still liberalize its visa procedures with as many Commonwealth realms as its government might like within the European Union, what with the continued fragmentation of the European Union's migration policies. The United Kingdom could always have chosen to leave the doors to its erstwhile colonials open.Quite frankly, many Canadians might prefer the United Kingdom to remain within the European Union in the case of such a liberalization.

I'll also note my skepticism of the motives of many of the proponents. Why include New Zealand but not Jamaica within this scheme? Jamaicans, as a community and as individuals, are far more likely to benefit from this liberalization than New Zealanders? If some people within the United Kingdom want to radically shift immigration policy, why not perhaps try to replace Poles with Jamaicans? The answers are obvious, and unflattering. The chief one is that these people do not want many immigrants at all, perhaps particularly the "wrong" type of immigrants. The pro-Brexit Anglospherists who offer up the idea of free migration with the richest and whitest of the old colonies could be accused of bait-and-switch, of wanting to exit a European Union where migration is a substantial presence for a mini-Commonwealth where migration is, if not less of an issue, more politically difficult. (What immigration policies, I wonder, are Canada and Australia and New Zealand supposed to adopt?) I'd accuse some of these of having hidden motives, but then some of them are quite open about their plans.

Thursday, October 01, 2015

On Population Matters, the Syrian refugee crisis, and the United Kingdom

While I was reading my RSS feed the other day, I came across an Open Democracy essay by Adam Ramsay with the eyecatching title of "The charity which campaigned to ban Syrian refugees from Britain". The British charity Population Matters, concerned with demographic trends in the United Kingdom and potentially unsustainable populations there, has opposed the resettlement of Syrian refugees there.

Amnesty has called on the UK and other EU countries to 'significantly increase the number of resettlement and humanitarian admission places for refugees from Syria'. Yet the UK has Europe's fastest growing population and England is one of Europe's most densely populated countries. People have difficulty finding homes and jobs and even getting a seat on public transport. Our cost of living is rising as our growing population requires ever greater expenditure on infrastructure projects to meet this growing demand. It is becoming ever harder to protect our environment and to limit our contribution to climate change as numbers climb inexorably.

Instead, the UK and other EU countries should continue to support migrants from the Syrian civil war and other conflicts in the countries adjacent to those conflicts. In addition, the international community should consider intervening in long running conflicts with regional implications.

This Ramsay has connected the underlying themes of racism and xenophobia which, he argues, are present in this movement.

Population Matters has long called for “zero net-migration” to the UK: essentially, “one in, one out” - a position more extreme than the BNP. It's not just them. Last year, the Swiss organisation Ecopop (as in “ecology” and “population”) launched a referendum campaign calling for net immigration to be cut to 0.2% of the country's population. Swiss people need, as they put it, “lebensraum”. In their January 2015 magazine, the Swiss referendum campaign was the top item in Population Matters “international movement” section.

It's not just their extreme views on migration which are controversial. Among Population Matters' six policy proposals for the recent general election was a suggestion that child benefit and tax credits should be scrapped for third and subsequent children. With child poverty as high as it is in Britain, it must have been the only charity in the country celebrating as Osborne subsequently cut tax and universal credits for third and subsequent children. Many were surprised by the Chancellor's decision, but, as Polly Toynbee put it, “there was always a eugenic undercurrent in Tory thinking: stop the lower classes breeding.”

Of course, none of this is new. Malthusian arguments have been used to justify brutal policies ever since the British civil servant responsible for Ireland, Sir Charles Trevelyan, wrote that the great famine there was an “effective mechanism for reducing surplus population”.

This genocidal tradition is, of course, not represented in contemporary Malthusianism. But the broader questions of race and gender are uncomfortable for them. The organisation wraps itself in the flag of women's empowerment and concern for global poverty, and I am sure that for most of those involved in it, those are genuine worries. But any interrogation of these issues ends in a deeply problematic place. George Monbiot, as ever, puts it in the clearest terms: “People who claim that population growth is the big environmental issue are shifting the blame from the rich to the poor”.

This article got quite a lot of attention, in the comments at Open Democracy, in the blogosphere (see the Bright Green blog), and eventually from Population Matters. In "7 reasons why some progressives don’t get population", Chief Executive Simon Ross responded to the criticisms. For instance:

Migration is running at unprecedently high levels and is the British public’s greatest concern. People can see the impact of one of Europe’s highest levels of population density and population growth, particularly in London and the south east – a growing insufficiency of affordable housing, conveniently located education, responsive healthcare and comfortable transport. These all hit the poorest hardest. However, progressives typically consider themselves internationalists, with a hearty welcome for others, and so would rather not address the issue. We think there has to be limits to migration for any society concerned about environmental sustainability. That doesn’t mean no immigration. If well managed, UK emigration of 300,000 each year provides plenty of leeway for admitting some refugees while achieving balanced migration. That said, the huge numbers involved, with three million fleeing Syria alone, preclude migration being a solution for most.

I would note that, in fact, no one has proposed resettling the three million Syrians in the United Kingdom. I would also note, after Ramsay, that countries where Syrian refugees are concentrated, particularly Jordan and Lebanon, are facing absolutely and proportionally much greater stresses than the United Kingdom in Ross' implied scenario with fewer resources.

More broadly, I would also observe that Ross' scenario actually doesn't prescribe very specific for the Syrian refugees. What, exactly, are they supposed to do? Should they stay in Jordan and Lebanon, perhaps seek resettlement elsewhere, perhaps return to Syria? Ross' essay talks at length about how everyone is responsible, but it also provides no concrete solution. Earlier in his essay, Ross talks about the world of the ideal versus the world of the material, but he addresses neither in regards to the Syrians. This leaves me profoundly suspicious. I'd find a straightforward statement that the refugees should be left to hang more honest, in truth, than the statement that something could possibly be done, hopefully, if all goes well.

What do you think of this?

Labels:

demographics,

middle east,

migration,

refugees,

syria,

united kingdom

Friday, July 24, 2015

On "The Wetsuitman"

I recently came across an English-language article in Norway's Dagbladet, "The Wetsuitman". Written by Anders Fjellberg and featuring photos by Tomm W. Christiansen and Hampus Lundgren, it's a superb if very sad piece of investigative journalism that takes two wetsuit-clad bodies found on the shores of the North Sea and uses them to examine such phenomena as Syria's war refugees and the desperate attempts of migrants to enter the United Kingdom from France. That it does not provide easy answers to any of the situations it describes is a strength, as there are none.

Labels:

european union,

links,

migration,

netherlands,

norway,

refugees,

syria,

united kingdom

Wednesday, January 14, 2015

On Steve Emerson, #foxnewsfacts, and bad pop demography

Steven Emerson's gaffe about the British city of Birmingham, stating in a live television interview that "[I]n Britain, it’s not just no-go zones, there are actual cities like Birmingham that are totally Muslim where non-Muslims just simply don’t go in", has gotten global coverage. (For the record, in Birmingham, the United Kingdom's second-largest city by population, Muslims make up 14.3% of the city's population.)

Informed Consent's Juan Cole notes correctly that Emerson has consistently gotten things wrong, assigning responsibility for the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing to Muslims. One question still has to be asked: How could someone with his reputation get global media coverage? I'll suggest the trending Twitter hashtag #foxnewsfacts wasn't picked arbitrarily

Meanwhile, this would seem to fit with the pattern I mentioned last week of people badly misjudging the size of populations, overestimating them. Joe. My. God. has noted that the same sort of thing goes on with non-heterosexuals, too. The suggestions of the commenter here, that minorities tend to concentrate in cities and that cities are often taken to accurately represent their countries, do point in a plausible direction.

I think one of the primary reasons is the that Immigrants concentrate in the cities.

In my neck of the woods, the rural areas and the suburbs are almost completely white European in decent. But if you go to the local city (which is a small American city that you have never heard of) it is a regular United Nations full of Muslims, Hindus, Orthodox Christians (as exotic to the locals as the other faiths).

The end result is that were people live is more homogeneous then the country at large but where they go to socialize and shop is far more diverse then the country at large. And I think that people get their preconception of what the country as a whole is like not from where they live but from where they shop.

How often have conservatives and nationalists castigated cities, especially large ones, as unrepresentative of their community--too multiethnic, too "cosmoplitan", too secular, et cetera?

Labels:

demographics,

eurabia,

links,

statistics,

united kingdom

Friday, June 14, 2013

On the problems of David Goodhart on immigration in the United Kingdom

I was alerted by a post by Yorkshire Ranter Alex Harrowell about Jonathan Portes' review of David Goodhart's new book about immigration in the United Kingdom, The British Dream. The title? "An Exercise in Scapegoating".

The problem with Goodhart's book, simply put, is that it doesn't appear to deal with facts.

There are two major problems with contemporary British society, according to David Goodhart in The British Dream, and both are primarily caused by immigration. The first problem is economic: the plight of the white working class, especially the young, and the decline of social mobility. Goodhart argues that low-skilled immigrants have taken jobs from unskilled natives, leaving them languishing on benefits, while high-skilled immigration reduces both the incentives and opportunities for ambitious and talented natives to move up the ladder. Many find this thesis convincing, and it has been accepted as fact by much of the political elite. There is, however, almost no evidence to support it. The second problem is social: the decline of a shared sense of community, local and national, which Goodhart relates to the failure of at least some immigrants to integrate, either ‘physically’ (where they live, who their kids go to school with, what language they speak and so on) or ‘mentally’ (in terms of the degree to which they identify with Britain, or share a common set of values). Some may think this argument has more force, but again, his conclusions far outrun the facts.

I’ll start with the economics. Goodhart gives a fair summary of the current consensus about the effects of immigration on the labour market. It comes in two parts. First, in the medium to long term the ‘lump of labour’ fallacy is just that: it isn’t true that the number of jobs in the economy is fixed, and more jobs for immigrants doesn’t mean fewer for natives. Second, the evidence suggests that in the UK immigration has little or no impact on employment even in the short term; it may drive down wages for the low-skilled, but the effect is small compared to that of other factors (technological change, the national minimum wage and so on). These things are now well established, and Goodhart appears to accept them. So it comes as something of a surprise that he should cite with approval Fraser Nelson’s observation that mass immigration ‘broke the link between more jobs and less dole’[.]

[. . .]

Goodhart cannot escape from his instinctive view that the political economy of immigration is a zero-sum game, even as he accepts that both economic theory and the evidence say no such thing. ‘A disproportionate number of new jobs,’ he writes, ‘seem to have been going to recent immigrants.’ But this is an expression of the ‘lump of labour’ fallacy he elsewhere dismisses. The belief that if immigrants get ‘more’ of something (jobs, education, opportunities, political power), natives (or whites) must get less. This guides his discussion of the local economic impact of immigration in Merton, South-West London: ‘Poor whites [are] doing the worst of the lot.’ Such people have ‘mainly opted out: they seldom vote, and a lot of the younger people are “Neets” – not in employment, education or training.’ It isn’t entirely obvious from Goodhart’s description of Merton why immigration is responsible for this. Do the immigrants displace natives from jobs, schools and polling booths, or do they somehow drag them down? Either way, such facts as there are in this sentence appear to be wrong. Do fewer working-class whites vote in Merton than elsewhere? I’m not aware of the existence of any statistics on local voting by ethnicity or class, but both the Merton constituencies (Mitcham and Morden, and Wimbledon) had a higher than average turnout at the last election, and more than two-thirds of Merton voters are white. As for Neets, the Merton Council report cited by Goodhart found 87 white Neets aged 16-18. Is that a lot? Not really: there are about 2300 whites in the relevant age group. Whether the council’s data are directly comparable with official statistics isn’t certain, but if they are then the chances of a white teenager being Neet are considerably lower in Merton than they are nationally. (The official statistics suggest that Merton’s Neet rates are pretty low.)

More, Goodhart's problems with facts seem to have unsettling inclinations.

Goodhart is of course right that young Brits, especially those not from middle-class backgrounds, are having a pretty hard time. But the question is why. Think about it this way. Suppose you’re poor, young and white: where in the UK don’t you want to be? That’s a subjective question. But from an economic point of view, one might want to consider such criteria as the proportion of young people who don’t get decent GCSEs and the number who are out of work. By those yardsticks, the answers are reasonably clear. Nationally, just under 60 per cent of kids whose first language is English get five good GCSEs including maths and English. There are eight local government districts where that figure dips below 50 per cent: Hartlepool, Middlesbrough, Knowsley, Blackpool, Barnsley, Hull, Nottingham and the Isle of Wight. Job prospects for young white school-leavers in these areas are, not surprisingly, poor: the proportion on the dole ranges from 12 to 18 per cent, compared to the national average of about 8 per cent. Yet of these areas, only Nottingham has a substantial non-white or immigrant population. In London, children whose first language is English are somewhat more likely (about 62 per cent) than the national average to get five good GCSEs, despite considerably higher poverty rates. Young whites in London don’t often end up on the dole: only about 5.5 per cent, close to the lowest rates in the country. Things are a little worse in Merton, where GCSE results are about average, and the proportion of young whites claiming benefits is about 6.5 per cent, but that’s still well under the national average.

So, to put it bluntly, if you’re going to be white, British and poor, all the statistical evidence suggests you’d be better off being born in Merton – or anywhere else in London, surrounded by immigrants – than in the mostly white areas where educational outcomes, in particular, are worse. We need to be careful here. Correlation doesn’t imply causation. There are lots of possible explanations for the figures I have given; in particular, the remarkable improvement in London’s schools, especially for more disadvantaged children, over the last decade. And there’s little doubt that the depression of local economies in some Northern cities is responsible for both the high unemployment and relatively low immigration in those places. Econometric analysis suggests that there’s little or no association between high immigration and employment or unemployment rates.

And:

Goodhart [makes] an absurd, some would say offensive, analogy with the US. Talking about Waltham Forest in North-East London, he writes: ‘In America, this is called Sundown Segregation; people mixing during the day but going home to quite separate neighbourhoods.’ ‘Sundown towns’, as the sociologist James Loewen has documented, were places in the US where, before the enactment of civil rights legislation, black people (sometimes in earlier years also Chinese, or Mexicans) were not permitted to remain after dark. I’m not sure which is worse: the irrelevance of this concept to modern Britain; the failure to do the elementary research required to establish the origin of the term; or the ugliness of comparing Waltham Forest to American towns that once displayed signs reading ‘Don’t let the sun set on you, nigger.’

Even worse is Goodhart’s discussion of specific communities where there are very real economic and social problems. I know little about Bradford, so have no firm basis on which to judge his plausible-sounding claims about the Pakistani immigrant experience there: much higher segregation than in London, the dominance of clan politics, the impacts of chain marriage migration etc. A friend in Bradford – a professional, leftish woman of Pakistani origin, working in education – told me that what he has to say is ‘unscientific’, based on ‘cheap anecdotes and quite frankly baloney’. No reason you should take her word for it, so let’s provisionally accept Goodhart’s suggestion that there is a prima facie case that first-cousin marriage is responsible for a higher than average proportion of birth defects among Bradford Pakistanis. He cites some relevant research, but follows it up with assertions which are unsubstantiated, inaccurate and alarmist: ‘Bradford has just opened two more schools for children with Special Educational Needs,’ he writes. ‘On some measures nearly half of all children in the area qualify for special help.’ No source. However, the Department for Education publishes the statistics, and it turns out that in Bradford, the proportion of children who ‘qualify for special help’ is about 21 per cent. Well, 21 per cent is not ‘nearly half’. It is, in fact, only slightly higher than the national average of 20 per cent. And it is significantly lower than in some other, mostly white places. Nationally, the highest figure is 27 per cent, in north-east Lincolnshire. What’s going on? Maybe the locals marry their cousins there too. But I think I’ll restrict myself to saying that this is a complex phenomenon on which I’m no expert. It’s a pity Goodhart didn’t do the same.

David Edgar's Guardian review touches on this.

Many elements of this narrative are questionable. Set against comparable countries, Britain's current immigration level is average: both Germany and France have higher numerical foreign-born populations, and 11 EU countries have immigrant populations which are proportionately higher than ours. It's true that less than half of current immigration comes from the EU, but emigration by non-EU citizens is higher too. As Goodhart acknowledges, more than 70% of current immigrants stay less than five years, because so many of them are students (only half of the headline four million have settled here). Studies of the 2011 census indicate that large cities such as Birmingham and Bradford have seen a decrease in segregation for most ethnic groups; in London, the decrease is particularly notable among Bangladeshis.

The argument that racism is greatly exaggerated doesn't really stand up either. The five-fold increase in the number of racist attacks since the early 90s may be partly due to changing definitions, but the absolute 2011-2012 figure of 47,678 racist incidents in England and Wales, of which 35,816 were recorded by the police as race-hate crimes, is a dramatic figure in itself. Goodhart's argument that press demonisation of immigrants contributes positively to race relations by providing "a psychological safety valve" is clearly self-serving. On pay, a 2008 report to the Equality and Human Rights Commission found that the earnings of Pakistani and Bangladeshi men at the low and middle levels of education were only two thirds of those of similarly qualified white men. On employment, male Chinese graduates are over three-quarters less likely to be employed than their white peers. And while Goodhart acknowledges the results of the so-called "CV tests", revealing that employers are still less likely to employ applicants with ethnic minority names, he justifies the discrepancy on the grounds that such people might prove "a source of tension and embarrassment" in the workplace, as, after all, "people will generally give preference to, and feel more comfortable being around, people they are familiar with". Acting on such attitudes as an employer has, of course, been illegal since the passage of the 1968 Race Relations Act.

[. . .]

Of course Goodhart acknowledges the cultural and (in a selective kind of way) the intellectual contribution of Britain's postwar immigrant communities. But recognising the changes that were brought about not in restaurants or at concerts or universities, but in workplaces and on the streets, through campaigns that were initially resisted by large sections of the host community, challenges the notion of a unified, linear national story. Goodhart's insistence that integration cannot be a "two-way street" and that immigrants "must carry the burden of any adaptation that is necessary" raises the question of what is being adapted to.

Harrowell has written at length about Goodhart's radicalization, here, noting (after a blog post by Portes) Goodhart's own claims that the United Kingdom is being run by people who care more for the benefits of people in Burundi than of people in Birmingham.

Well, we've been warned.

Labels:

demographics,

immigration,

migration,

politics,

united kingdom

Thursday, February 21, 2013

"Why Permanent Residents Should Be Allowed to Vote in Toronto"

Writing for the Toronto blog Torontoist, Desmond Cole recently suggested that permanent residents in the city of Toronto should be able to vote in municipal elections.

In 2006, Ryerson municipal affairs expert Myer Siemiatycki estimated that at least 250,000 Toronto residents, or 16 per cent of the city’s population, could not vote in municipal elections because they were not citizens. He describes this as a “lost city” of residents—who pay municipal taxes through their mortgages or rent, and contribute to services and programs through various user fees—but have no say in electing the mayor, city council, and school board trustees.

We have much to gain from giving permanent residents a direct say in Toronto’s election. Those who use and pay for services have a right to hold their relevant elected officials to account.

It is important for these residents to feel as welcome to shape programs and services as any citizen. Non-citizen residents can do this through advocacy, public consultations, and many other general forms of engagement, but with voting comes a more powerful kind of inclusion, symbolic and otherwise. Extending the vote empowers those who qualify to proudly identify themselves as fully engaged participants in civic life, not merely ratepayers or service users. Having more Torontonians taking up this responsibility is a good thing for our politics.

In Thorncliffe Park, a central east Toronto neighbourhood, one in three people is a child between five and 13 years of age. Thorncliffe is also home to immigrants from South America, South Asia, and the Middle East. But parents of children in Thorncliffe can’t choose their school board trustee simply because they are not citizens. Yes, politicians in these neighbourhoods are charged with representing everyone, non-voting residents included. But at election time, their decisions not to canvas houses, apartment buildings, and areas with high non-citizen populations tells those residents that their opinions matter less because they are not the ones going to the polling stations.

Canada has one of the highest rates of naturalization, or turning immigrants into citizens, in the world. Statistics Canada found in 2006 that four in five Canadian immigrants had become citizens, and that figure was on the rise. Some see this as an argument against extending the franchise to non-citizens: if most immigrants will become citizens anyway, why not wait until they have to give them the vote? But this is backwards. Since we know the vast majority of immigrants will pursue and obtain citizenship, delaying what in most cases will happen anyway is an artificial barrier to more robust participation in civic life.

The post was controversial, accumulating (at present) 58 comments. Many were opposed to the idea on principle, while others saw it as less necessary than boosting political participation including voting among people who are citizens already. Cole's rationale, though, does appeal to me, all the more so since--as he points out--any number of countries already do allow foreigners resident the vote in local elections. Most germanely, European Union citizens can vote in municipal and European Parliament elections across the Union, while Commonwealth citizens has access to the electoral roll in a diminishing number of countries. (Perhaps surprisingly, given the trend in the United Kingdom to limit Commonwealth citizens' access to the country, Commonwealth citizens still have the vote. In Canada, in marked contrast, the tendency has been to move away from this principle.)

Labels:

canada,

commonwealth,

european union,

politics,

toronto,

united kingdom

Tuesday, February 19, 2013

Taking a look at Jonathan Last's arguments on migration

Demographics writer Jonathan Last (Wikipedia article, official site) has gotten a fair bit of attention for his Wall Street Journal essay "America's Baby Bust", wherein he argues that the United States' slowing economy is directly connected to low fertility. Much of the reaction to his analysis has been critical. Writing in The New Republic, Rui Texeira questions Last's dismissal of immigration and his piecemeal remedies for low fertility (tax breaks as opposed to government programs). It's taken apart scathingly by Love, Joy, Feminism!'s Libby Anne, who rightly finds Last's equation of Chinese forcible one-child policy with small American families ridiculous, Last's dismissal of the idea that things could be done to make family life easier on the grounds that people shouldn't necessarily expect happiness ill-guided, and makes an argument that Last's focus on fertility of well-off white American women reflects the "race suicide" rhetoric of early 20th century American eugenicists.