Tuesday, November 27, 2007

Trends in Land Use and Attitudes Regarding the Same in Europe

Newsweek International posted a story this summer to its website from its July 4, 2007 issue with a summary line as follows: “Economics and declining birthrates are pushing large swaths of Europe back to their primeval state, with wolves taking the place of people.” The article describes a trend in Europe’s rural areas of “ultralow birthrate(s) and continued rural flight”…to the extent that “rural flight continues to suck people into Europe's suburbs and cities.” The UN and EU are quoted to the effect that by 2030 the rural areas of the EU 25 “will lose close to a third of its population.”

The article describes some examples of changes in wildlife populations:

“In 1998, a pack of wolves crossed the shallow Neisse River on the Polish-German border. In the empty landscape of Eastern Saxony, speckled with abandoned strip mines and declining villages, the wolves found plenty of deer and rarely encountered humans. They multiplied so quickly that a second pack has since split off, colonizing a second-growth pine forest 30 kilometers further west.”

“In Swiss alpine valleys, farms have been receding and forests are growing back in. In parts of France and Germany, wildcats and ospreys have re-established their range.”

Bizarrely, some environmental groups in Europe don’t want farmland to revert to a wild state. The article claims that “The scrub brush and forest that grows on abandoned land might be good for deer and wolves, but is vastly less species-rich than traditional farming, with its pastures, ponds and hedges”, and quotes Jan-Erik Petersen, a landscape biologist at the European Environmental Agency in Copenhagen as saying that "Once shrubs cover everything, you lose the meadow habitat. All the flowers, herbs, birds and butterflies disappear…a new forest doesn't get diverse until it's a couple of hundred years old." Such ideas seem to contradict the goals of environmental groups in the US which as far as I can tell seek to allow farmland to revert to a natural state. I doubt that there is meaningful research that supports Petersen’s assertion.

The article states that ‘Keeping biodiversity up by preventing the land from going wild is one of the reasons the EU pays farmers to mow fallow land once a year. France and Germany subsidize sheep herds whose grazing keeps scenic heaths from growing in.” That seems absurd to me. The article goes on to say that “Outside the range of these subsidies—in Bulgaria, Romania or Ukraine—big tracts of land are returning to the wild.” I seriously doubt that biodiversity will be a problem in these areas.

The article describes an attitude toward the landscape such that it “is glued to the European identity, reflecting what the Germans call "Kulturlandschaft"—a landscape shaped by centuries of human care”, and says that “Many Europeans are reluctant to just let nature do its thing.” This attitude doesn’t seem to square with the seeming momentum of Europe’s Green movement, and certainly has received very little attention in the US.

Tuesday, November 06, 2007

Argentina Fertility, Demography and Economic Growth

The topic of this post is Argentina, and it is a timely one, since Argentina just had some reasonably well publicized elections. Argentina has also been in the news to some extent for the rather shabby way in which it has been managing its inflation statistics, and for the fact that its energy infrastructure is little better than a walking - or crawling - disaster. On top of this we have the fact that Argentina does not exactly have the most business friendly or competitive institutional environment, indeed Argentina just clocked in at 85th place in the World Economic Forum's Global Competitiveness Index

All of this then makes it rather surprising to discover that Argentina has in fact enjoying rather stellar economic growth over the last few years, since coming out of the major crisis which took place there around the turn of the century.

In fact the really big, big news which lies behind the recent electoral triumph of Cristina Fernandez isn't to be found the technique which has been so delicately refined in order to prune Argentinian inflation data, nor is it even to be found in the fact that earlier in the year many of the country's factories were brought to a virtual standstill by the need to maintain supplies to Argentina's domestic consumers (and of course voters) in the face of growing shortages. No, the principal "big picture event" which has marked this years electoral process is the fact that Argentina's economy has been expanding at a sustained annual pace of around 8% per annum over the last four years, and is, if anything, accelerating at the present time, since the Argentine economy reportedly expanded at the fastest pace in three months in August and was growing at an annual rate of 9.2%. Obviously the "China phenomenon" - if we can use the expression to characterise those emerging economies which now seem able to sustain very high levels of annual GDP growth (Turkey, India etc) - is something which now extends way beyond China. And the mention of China is not altogether incidental here, since it was by linking-in to China's growing need for agricultural products (and in particular for Soya) that Argentina first began to put the turn of the century crisis behind it.

So, the interesting question is, if we can't put this sudden change of fortune down to good economic management, or if we can't attribute it to sound institutions, then just what can we attribute it to?

Its the Demography, Silly!

Well for anyone taking a long hard look at Argentina's recent economic growth in recent years - as I did in this post here - one thing certainly stands out clearly enough, and that is the underlying sea change which has taken place in Argentina's demography.

As is evident even from the most cursory glance, Argentina's fertility rate has been falling for many years now, and at this point just about to go below the population replacement level.

This fall in the fertility rate has lead to a steady slowing down of the rate of increase in the number of children born, and since 2000 the number has leveled off, and even begun to fall back slightly.

At the same time life expectancy has been improving steadily.

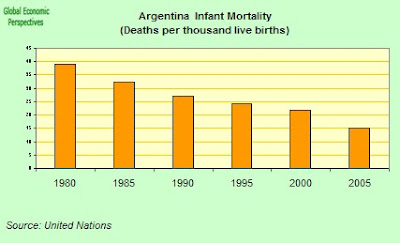

Most notably life expectancy has been approving among the young and poor, and in particular this can be noted in the steady decline in infant mortality which has been taking place in Argentina.

As a result of these processes Argentina's population is still increasing, but again at a much slower rate than hitherto.

One consequence of all of this is that the percentage of the population in the 0 to 14 age group has been declining steadily from the high point reached at the end of the 1980s.

All of this is producing profound changes in Argentina's age structure, changes which are associated with what is known in an economic context as the demographic dividend. These changes can be seen reasonably clearly in the following population pyramids which are for 1990, 2000 and 2010 respectively. Looking at the pyramids we can see how their shape begins to change, and particularly in the third pyramid we should note how the steady stabilization, and then subsequent decrease, in the number of children born means that the generation size starts to shrink. It is the appearance of this change at the base of the pyramid which is the most typical indicator of the presence of the demographic dividend.

There are a number of reasons why changes in age structure affect economic performance (the growing proportion of the population in the working age groups, for example, or the much healthier working population), but one of the most important of these in the context of a developing economy like Argentina is undoubtedly the impact that such changes have on saving and investment. Basically the relative decline in the proportion of young children frees off a greater proportion of national resources for saving and investment, and it is this process which means that the dependence on external funding begins to decline. A similar process has been observed in China since the late 1990s, and is now being observed in India.

There are a number of reasons why changes in age structure affect economic performance (the growing proportion of the population in the working age groups, for example, or the much healthier working population), but one of the most important of these in the context of a developing economy like Argentina is undoubtedly the impact that such changes have on saving and investment. Basically the relative decline in the proportion of young children frees off a greater proportion of national resources for saving and investment, and it is this process which means that the dependence on external funding begins to decline. A similar process has been observed in China since the late 1990s, and is now being observed in India.

Also we can note a slight but perceptible decrease in the consumption share in GDP in Argentina in recent years from 78.5% in 2004 to 76,6% in Q2 2007, and a steady increase in the investment share from 17.8% in 2004 to 21.1 in Q2 2007. These are again features that tend to be noted as the demographic dividend works its way through and the declining pressure of immediate consumption which comes from a lower proportion of under 15 year olds frees off more national resources for saving and thus for investment.

To Cry.... or To Laugh?

So to end where I started, with a question - should we be crying right now for Argentina? My answer would be most definitely that we should not. There may be a lot - a hell of a lot - wrong with the way Argentina is being run, and some of the issues arising have been addressed in this post. But the underlying situation in Argentina is far from being a tragic one this time round. History it sometimes seems is condemned to eternally repeat itself in Argentina, now as tragi-comedy, and then again as surreal farce, but there does seem to be a line of advance there, and this time round the line of advance might just lead to real economic development.

Clearly Argentina needs to move away from such 'old-school' practices as manipulating the statistical system. And clearly Argentina also needs to move forward and attract Foreign Direct Investment in a greater quantity than hitherto in order to modernise its energy sector and indeed its infrastructure generally. But the present situation is far from being a hopeless one, and reform is not only possible but probable. Not only that, more by accident than design Argentina may go into the next global growth slowdown better equipped to be able to withstand the pressure than many others. If so this will also be a test, a test for the relative importance of institutional quality when measured against the driving force of demographic tailwinds. The outcome of this test promises to be interesting, most interesting, and for all of us.

References

Further reading on the topic of the Demographic Dividend, which at the end of the day provides the theoretical prop which underlies this post, can be found in:

The Economics of Demographics, Special Issue of the IMF publication Finance and Development, September 2006.

Global Demographic Change: Dimensions and Economic Significance. David Bloom and David Canning. Harvard School of Public Health. Working Paper No. 1

The Demographic Dividend. Demography Matters own category section, with a collection of our posts on this topic.