- Old age popped up as a topic in my feed. The Crux considered when human societies began to accumulate large numbers of aged people. Would there have been octogenarians in any Stone Age cultures, for instance? Information is Beautiful, meanwhile, shares an informative infographic analyzing the factors that go into extending one’s life expectancy.

- Growing populations in cities, and real estate markets hostile even to established residents, are a concern of mine in Toronto. They are shared globally: The Malta Independent examined some months ago how strong growth in the labour supply and tourism, along with capital inflows, have driven up property prices in Malta. Marginal Revolution noted there are conflicts between NIMBYism, between opposing development in established neighbourhoods, and supporting open immigration policies.

- Ethnic migrations also appeared. The Cape Breton Post shared a fascinating report about the history of the Jewish community of industrial Cape Breton, in Nova Scotia, while the Guardian of Charlottetown reports the reunification of a family of Syrian refugees on Prince Edward Island. In Eurasia, meanwhile, Window on Eurasia noted the growth of the Volga Tatar population of Moscow, something hidden by the high degree of assimilation of many of its members.

- Looking towards the future, Marginal Revolution’s Tyler Cowen was critical of the idea of limiting the number of children one has in a time of climate change. On a related theme, his co-blogger Alex Tabarrok highlights a new paper aiming to predict the future, one that argues that the greatest economic gains will eventually accrue to the densest populations. Established high-income regions, it warns, could lose out if they keep out migrants.

Showing posts with label malta. Show all posts

Showing posts with label malta. Show all posts

Wednesday, March 20, 2019

Some links: longevity, real estate, migrations, the future

I have been away on vacation in Venice--more on that later--but I am back now.

Labels:

ageing,

atlantic canada,

canada,

cities,

demographics,

diaspora,

economics,

future,

futurology,

history,

islands,

links,

malta,

migration,

moscow,

nova scotia,

prince edward island,

russia,

syria

Tuesday, March 29, 2011

Post-colonialism and migration in Italy

An article about the recent surge in boat migration from Africa to Italy caught my attention with an interesting comparison.

The Albanian model? Frattini's comparison made a certain amount of sense, in that migration from Albania to Italy only began after the collapse of Communism in Albania let Albanians leave their impoverished for work. Frattini might be imagining that Tunisia without Ben Ali would trigger similar migration. If so, his comparison is off-base: the collapse of Communism in Albania led directly to the collapse of the Albanian economy and border controls, creating the incentive and the means for Albanians to leave their country, while the end of the Ben Ali regime in Tunisia coincided with harder times, yes, but not with an economic collapse comparable to post-Communist Albania's.

After I blogged here about Malta last month, I made a tie-in post at another group blog, History and Futility. Malta's current status as a democratic European nation-state embedded in the European Union is grounded on a particular interpretation of Maltese cultural and geographic realities. Other interpretations are possible.

Much the same sort of thing can be said about Italy, which had its own maps, its own perceptions of its neighbourhood. These perceptions were more aggressive by far than anything of the Maltese, granted.

I copied this map of Italian territorial claims under fascism from the Wikimedia Commons. As described by the creator brunoambrosio, it is a map of "the 1940 project "Greater Italia", inside the orange line and dots, in Europe and North Africa. Self-made (I have based my work on the original Commons Image:Mediterranean Relief.jpg, licensed PD-USGov). The green line and dots show the biggest extension of Italian control in the Mediterranean sea in november 1942 (while the red shows the British controlled areas, like Malta)."

Albania, source of modern immigrants to Italy, was firmly in the Italian sphere; Tunisia, then (under French protectorate) not a source of immigrants but rather as a target for irredentist sentiment and in many ways an Italian settlement colony, was included briefly; Libya, the "Fourth Shore" of Fascist Italy and core of the Fascist Roman Empire, was Italian for thirty years. Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Somalia are not shown here.

James Miller noted that for most of its history Italy was caught by the image of the Mediterranean as a forum for expansive imperialism, as a place where Italy could show off its emergent great power status and underline its modernity.

The post-colonial element in Italy's relationship to once-subordinate and migrant-receiving, now independent and migrant-sending, countries on its frontiers is something that doesn't seem to have been investigated that much, notwithstanding the origins of many of these unpopular immigrants in former Italian colonial or near-colonial countries (Tunisia, Eritrea, Somalia, Ethiopia) and the importance of post-Italian Libya as a corridor. It played a role: see how Italian links encouraged a relatively much greater volume of post-colonial immigration to Italy from Eritrea as opposed to Somalia. Where else does it play a role, though? What networks have been established? What attitudes are there in Italy towards migrants from ex-Italian colonies: empathy, dislike?

Italy has declared a state of emergency on the southern island of Lampedusa and appealed to the rest of the EU for help following the arrival of up to 5,000 people fleeing the political upheaval in Tunisia.

Silvio Berlusconi's foreign minister, Franco Frattini, said he had contacted Catherine Ashton, the European Union's high representative for foreign affairs, to propose a blockade of Tunisian ports by the EU's Frontex agency which could "mobilise patrols and refoulement [the forcible return of would-be migrants to their country of departure]".

He said a similar exercise was carried out by Italy when 15,000 Albanians arrived in 1991. "I hope the Tunisian authorities accept the Albanian model," Frattini said in an interview with the Corriere della Sera newspaper.

The Albanian model? Frattini's comparison made a certain amount of sense, in that migration from Albania to Italy only began after the collapse of Communism in Albania let Albanians leave their impoverished for work. Frattini might be imagining that Tunisia without Ben Ali would trigger similar migration. If so, his comparison is off-base: the collapse of Communism in Albania led directly to the collapse of the Albanian economy and border controls, creating the incentive and the means for Albanians to leave their country, while the end of the Ben Ali regime in Tunisia coincided with harder times, yes, but not with an economic collapse comparable to post-Communist Albania's.

After I blogged here about Malta last month, I made a tie-in post at another group blog, History and Futility. Malta's current status as a democratic European nation-state embedded in the European Union is grounded on a particular interpretation of Maltese cultural and geographic realities. Other interpretations are possible.

The small light green circle surrounding the archiepelago reflects Malta’s identity as small and unique, isolated in the Mediterranean on its small land base and with its unique culture; the large purple circle to denote Malta’s location within a sort of Italian sphere of influence, more vestigial than before, thankfully, when Italy lay claim to Malta (and the other territories within the circle) as rightfully Italian regardless of local opinion; red denotes Malta’s links with North Africa, low key and unemphasized but real as evidenced by the Semitic Maltese language and the apparent popularity of post-independence Malta’s flirtations with a radically anti-colonial Libya; black, to show Malta’s location within the European Union, its hoped-for final destination. Different people can agree that Malta is located at 35°53′N 14°30′E and disagree on the relative importance of the different human factors–language, religion, migration, history, trade, politics–which assign meaning to those geographic coordinates.

Much the same sort of thing can be said about Italy, which had its own maps, its own perceptions of its neighbourhood. These perceptions were more aggressive by far than anything of the Maltese, granted.

I copied this map of Italian territorial claims under fascism from the Wikimedia Commons. As described by the creator brunoambrosio, it is a map of "the 1940 project "Greater Italia", inside the orange line and dots, in Europe and North Africa. Self-made (I have based my work on the original Commons Image:Mediterranean Relief.jpg, licensed PD-USGov). The green line and dots show the biggest extension of Italian control in the Mediterranean sea in november 1942 (while the red shows the British controlled areas, like Malta)."

Albania, source of modern immigrants to Italy, was firmly in the Italian sphere; Tunisia, then (under French protectorate) not a source of immigrants but rather as a target for irredentist sentiment and in many ways an Italian settlement colony, was included briefly; Libya, the "Fourth Shore" of Fascist Italy and core of the Fascist Roman Empire, was Italian for thirty years. Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Somalia are not shown here.

James Miller noted that for most of its history Italy was caught by the image of the Mediterranean as a forum for expansive imperialism, as a place where Italy could show off its emergent great power status and underline its modernity.

Students of literature often construct their understanding of a topic primarily from books and readings. But that’s not the case for students in Giuliana Minghelli’s new [Harvard] course on cultural migrations between Africa and Italy, where they have witnessed a performance by one of the assigned authors and have the opportunity to develop their own creative responses.

Minghelli, associate professor of Romance languages and literatures, found her interest in the subject piqued by her study of Italy’s early 20th century modernist writers. Many of them, she discovered, were either born in or had lived in Africa.

“People like Futurism founder Filippo Tommaso Marinetti chose Africa as the stage on which to perform the speed, modernity, action, and violence of his Futurist poetics,” Minghelli noted. “That is quite intriguing. Why Africa?”

On the one hand, she said, Africa represented a blank canvas onto which Italian writers could project their wildest fantasies. At the same time, the continent functioned as a land of exile and escape, initially from the fascist regime that controlled Italy in the decades leading up to World War II.

Later, in the 1960s, writers fled from the homogenization of capitalist consumer culture. For instance, author and film director Pier Paolo Pasolini traveled to Africa in search of an alternative, uncontaminated world.

Indeed, despite a desire on the part of many Italian authors to paint Africa as a primitive and exotic world, the continent is very close to Italy, perhaps uncomfortably so for many at the time. After the unification of Italy in 1861, Italians strove to present themselves as a thoroughly European culture, repressing what Minghelli calls “the Africa within Italy.”

Yet Italy also needed Africa, for economic reasons and because it was felt practicing colonialism would establish a stronger sense of national identity. The Italians were late to the “scramble for Africa,” waiting until 1936 — after the conquest of Eritrea, Somalia, and Ethiopia — to proclaim an official Italian Empire. The desire for conquest was buoyed by archaeological excavations in Africa that unearthed Roman ruins, which Italians used to link their colonizing activities to the glory of the Roman Empire.

“If you’re interested in the question of Italian nation-building and identity formation, Africa is really central,” Minghelli said.

The post-colonial element in Italy's relationship to once-subordinate and migrant-receiving, now independent and migrant-sending, countries on its frontiers is something that doesn't seem to have been investigated that much, notwithstanding the origins of many of these unpopular immigrants in former Italian colonial or near-colonial countries (Tunisia, Eritrea, Somalia, Ethiopia) and the importance of post-Italian Libya as a corridor. It played a role: see how Italian links encouraged a relatively much greater volume of post-colonial immigration to Italy from Eritrea as opposed to Somalia. Where else does it play a role, though? What networks have been established? What attitudes are there in Italy towards migrants from ex-Italian colonies: empathy, dislike?

Labels:

emigration,

european union,

italy,

libya,

malta,

tunisia

Thursday, February 24, 2011

On the Maltese immigrants in North Africa

The country of Malta has had many representations. Most recently, after its accession to the European Union in 2004 and to the Eurozone in 2008 while it became a major transit point and inadvertant destination for migrants, it has been imagined as a destination for migrants, perhaps peculiarly vulnerable owing to its small size and relatively tenuous economic state and national identity. Malta, as represented in the press, might be a beseiged battlement of Fortress Europe, located perilously close to the North African coast.

That's not the only way it's been seen. In fact, this time last century the situation was precisely the reverse. As small islands sometimes overpopulated relative to the productive capacity of their once-agricultural/military-driven economy part of the British global empire, from the mid-19th century on Malta experienced massive emigration, tens after tens of thousands of Maltese emigrants making their way throughout the British Empire and later Commonwealth and beyond. Some settled in Canada, for instance, the nucleus of the Maltese-Canadian community (as described by Shawn Micallef) lying here in Toronto just a couple of subway stops to the west of my home beyond its eventual dispersal. Many Maltese chose not to leave home so far behind and instead immigrated to French North Africa, to the Algeria colonized since 1830 and the Tunisia made a protectorate from 1881. There, Maltese immigrants came to play critical roles in the colonization of North African territories at a time when population pressures in Europe made the organized settlement of the southern rim of the Mediterranean Sea by Europeans seem a sensible idea.

Settlement in Tunisia began later.

Go, read, and reflect on the interesting ways in which history can more than reverse itself in short periods of time. Malta wasn't the territory experiencing pressure from ill-regulated immigration; Maltese, rather, were settlers making new homes in the conquered territories just beyond the horizon.

That's not the only way it's been seen. In fact, this time last century the situation was precisely the reverse. As small islands sometimes overpopulated relative to the productive capacity of their once-agricultural/military-driven economy part of the British global empire, from the mid-19th century on Malta experienced massive emigration, tens after tens of thousands of Maltese emigrants making their way throughout the British Empire and later Commonwealth and beyond. Some settled in Canada, for instance, the nucleus of the Maltese-Canadian community (as described by Shawn Micallef) lying here in Toronto just a couple of subway stops to the west of my home beyond its eventual dispersal. Many Maltese chose not to leave home so far behind and instead immigrated to French North Africa, to the Algeria colonized since 1830 and the Tunisia made a protectorate from 1881. There, Maltese immigrants came to play critical roles in the colonization of North African territories at a time when population pressures in Europe made the organized settlement of the southern rim of the Mediterranean Sea by Europeans seem a sensible idea.

Algeria was for many years the most important country for Maltese migration within the zone of the Mediterranean. Under various aspects it was also the most successful and statistics show that by the middle of the nineteenth century more than half of Malta's emigrants had chosen Algeria as their country of residence. Although the French conquest had began in 1830, some Maltese had found their way to the area around the city of Constantine before the French connection had began. In 1834 a French governor for North Africa had been appointed, and as the French consolidated their foothold on Algerian territory, Europeans followed the French tricolor. Among the Europeans the Maltese were one of the largest groups, being outnumbered only by Spaniards and Sicilians.

Like all newcomers, the Maltese in Algeria did at first encounter hostility from the French. Continental Europeans looked down on other Europeans who came from the islands such as the Sicilians and the Maltese. It is true to admit that most insular Europeans were poor and illiterate. Some did have a criminal record and were only too ready to carry on with their way of life in other parts of the Mediterranean where their names were not publicly known.

French official policy was dictated by sheer necessity. France was a large and prosperous country. Its population was not enormous and many French peasants were quite happy with their lot. If the French needed colonists to make their presence permanent they had to turn to other sources to obtain their manpower. The French Consul in Malta was in favour of encouraging Maltese emigrants to settle in Algeria. He believed that the Maltese showed a distinct liking for France and the French. Although the Maltese under the British, they were not politically active and the French could accept them without any fear.

Another important man who favoured Maltese emigration to North Africa in general and to Algeria in particular was the prominent French churchman, Cardinal Charles Lavigeric who had dreams of converting the Maghreb back to Christianity. Lavigerie saw North Africa in historical terms as he was professor of Church history. He founded a religious order which was . commonly called "The White Fathers" with scope of spreading Christianity among the .Berbers and the Arabs. Cardinal Lavigerie was archbishop of Carthage and Algiers. In 1882 Cardinal Lavigerie visited Malta. He immediately appreciated the Catholic fervour of the islanders. During his stay he talked of the Maltese as providential instruments meant to augment the Christian population of French North Africa. He saw the Maltese as loyal to France and to the Catholic Church and at the same time as being eminently useful in building some form of communication with the Arab masses.

[. . .]

By 1847 the number of Maltese living in Algeria was calculated at 4,610. The Maltese colony in Algeria had been realised as being of some importance by that date, so much so that Maltese church leaders decided to send two priests during Lent to deliver sermons in Maltese.

In a letter written by the Governor General of ,Algeria on June 17, 1903, it was stated that by then there were 15,000 inhabitants who claimed Maltese origin. Most of these were small farmers, fishermen and traders. As in other parts of North Africa, the Maltese ability to speak in three or four languages helped them to get on well with the French, Spaniards, Italians and Arabs.

In 1926 the number of ethnic Maltese living in Algeria and Tunisia was tentatively calculated at about 30,000. The exact number of Maltese in was impossible to arrive at because many Maltese had opted for French nationality. By 1927 the Maltese were considered as excellent settlers who worked very hard and were honest in their dealings with others. This was the judgement given by Monsieur Emile Morinaud, a Deputy for Algiers in Paris. In a speech delivered by Morinaud on November 30, 1927, the French politician declared the Maltese as being "French at heart".

Settlement in Tunisia began later.

When Napoleon Bonaparte captured Malta from the Knights of St. John in 1798 he ordered the Bay of Tunis to free all the Maltese slaves who languished in jail. At least fifty such slaves returned to Malta. For centuries the Maltese who found themselves in Tunis probably did so against their will. With the advent of the Napoleonic Era and the re-structuring of political power in Europe and along the shores of the Mediterranean, the pirates of Tunis lost their trade. The foothold gained by the French in North Africa changed the political framework of the Maghreb and some Europeans thought, somewhat prematurely, that the Mediterranean was to enter into another Roman Epoch. with peace reigning all along its coasts.

The Maltese were among the first to venture in their speronaras into Tunisian waters. They traded with coastal towns and with the island of Jerba. Eventually they established settlements not only in Tunis and on jerba but also in Susa, Monastir, Mehdia and Sfax. By 1842 there were about 3,000 Maltese in the Regency. In less than twenty years their numbers increased to 7,000.

[. . .]

The French had one serious preoccupation in Tunisia. Italian immigrants had settled there in their thousands and Italy had coveted Tunisia for a very long time. The French occupation of Tunisia had gone down very badly with the Italians. The French wanted the Maltese to act as a counter-balance to the Italians. British consular statistics show that by the beginning of the twentieth century there were 15,326 Maltese living in Tunisia.

The Maltese in Tunisia worked on farms, on the railways, in the ports and in small industries. They introduced different types of fruit trees which they had brought with them from Malta. Moreover contact between Malta and Tunisia was constant because the small boats owned by the Maltese, popularly known as speronaras, constantly plied the narrow waters between Tunisia and the Maltese Islands.

Paul Cambon referred to the Maltese living in Tunisia as the "Anglo-Maltese Element". He was grateful that such an element proved to be either loyal to France or at least was politically neutral. In spite of rampant anti-clericalism in France, the French allowed the Maltese complete freedom of their religion. Cardinal Lavigerie was respected. The fiery leader of French anti-clericalism, Leon Gambetta, did not hesitate to state that when French priests spread not only religion but French culture, then they were to be allowed to carry on with their work without any restraint.

After 1900 it became legally possible for foreigners to buy land in Tunisia. After that year there was a number of Maltese landowners in that country. In 1912 trade between Tunisia and Malta had risen to more than two million francs. Cultural ties were kept alive by the frequent visits brass bands from Malta which were often invited to cross the water to help create a festive -mood when the Maltese in Tunisia celebrated the feast of their parish. On April 10, 1926, a Maltese newspaper commented on a visit made by the French President to Tunisia. The newspaper claimed that the President, Emile Loubet, had eulogised the Maltese as "a model colony".

Go, read, and reflect on the interesting ways in which history can more than reverse itself in short periods of time. Malta wasn't the territory experiencing pressure from ill-regulated immigration; Maltese, rather, were settlers making new homes in the conquered territories just beyond the horizon.

Wednesday, February 23, 2011

Joe Sacco, "Not in my country"

A tweet from Torontonian (and Maltese-Canadian) Shawn Micallef pointed me to the news that two Libyan fighter jet pilots defected (with their pilots) Monday, and one Libyan warship following yesterday. This latest episode in Libyan-Maltese relations ads a new twist in relations between the two countries, in the 1970s and 1980s quite close owing to Maltese left-wing politician Dom Mintoff's desire to move beyond dependence on Britain and Libyan interest in establishing a close relationship with some country.

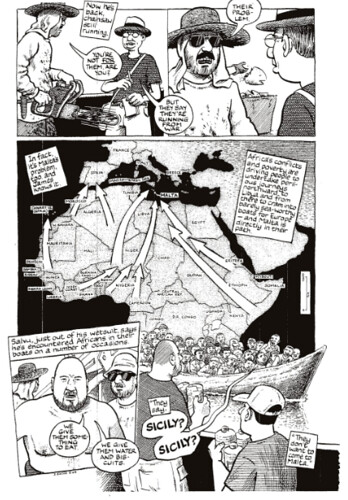

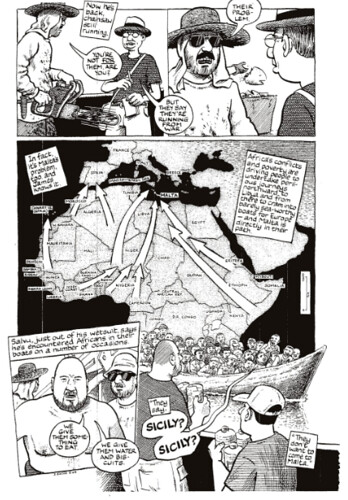

This is the latest episode in unexpected--unregulated--migration from Libya to Malta. I'd like to point our readers to Maltese-American graphic novelist Joe Sacco's 2010 graphic novel "Not in my country", available online at the website of the Guardian and providing an affecting and information look on the phenomenon of unregulated/irregular/illegal migration to Malta.

While trans-Mediterranean migration is a major issue for southern Europe, it's a particular issue for a small insular Malta that already has one of the higher population densities in Europe and few ways for these migrants to make it to the European mainland--an Italy that would be the logical (and, likely, preferable) next step is unreachable. Sacco goes into detail in his work.

Go, read.

This is the latest episode in unexpected--unregulated--migration from Libya to Malta. I'd like to point our readers to Maltese-American graphic novelist Joe Sacco's 2010 graphic novel "Not in my country", available online at the website of the Guardian and providing an affecting and information look on the phenomenon of unregulated/irregular/illegal migration to Malta.

While trans-Mediterranean migration is a major issue for southern Europe, it's a particular issue for a small insular Malta that already has one of the higher population densities in Europe and few ways for these migrants to make it to the European mainland--an Italy that would be the logical (and, likely, preferable) next step is unreachable. Sacco goes into detail in his work.

Go, read.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)