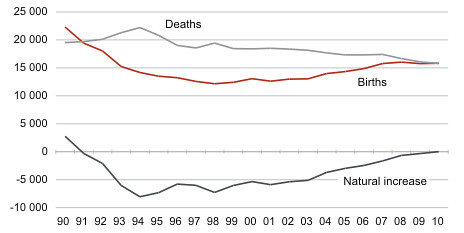

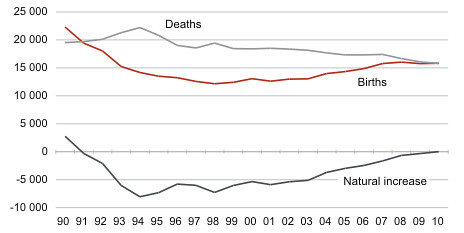

Thanks to Facebook's Urmas for letting me know the surprising news that Estonia has become--so far as I know--the first former Soviet republic in Europe (Azerbaijan and the rest of the Caucasus, perhaps, excluded--thanks for the correction, Anatoly) to experience

an excess of births over deaths since the fall of the Soviet Union. Yes, there seems to have been some improvement--I posted recently about Russia, after all--but it still stands out remarkably. Compare neighbouring Latvia's ongoing collapse.

According to the revised data of Statistics Estonia, in 2010 35 people more were born than died. The population of Estonia was 1,340,194 on 1 January 2011.

15,825 people were born and 15,790 people died in 2010. The number of births exceeded the number of deaths last 21 years ago in 1990.

In 2010, 62 children more were born than a year earlier but the number of births was still smaller by about 200 than the last decade’s record in 2008 when more than 16,000 children were born.

On the contrary the number of deaths has been rapidly decreasing during the last three years and in 2010 291 people less died than a year earlier. Thus the positive natural increase was mainly achieved due to the decrease in the number of deaths.

617,757 males and 722,437 females lived in Estonia at the beginning of 2011. Population growth continued due to the natural increase in Harju and Tartu counties.

Harju County's is Estonia's most populous, its 524 thousand people amounting to 39.2% of the Estonian population, while

Tartu County is Estonia's third most populous, home to just shy of 150 thousand people and 11.2% of the total population.

It's noteworthy that

Idu-Viru County, Estonia's third by population and located in the northeast of the country around the city of Narva on the Russian frontier, does not figure in this; so far as I know, Ida-Viru is continuing to experience continued natural decrease.

One of the most important facts about

Estonian demographics is the ethnic cleavage between ethnic Estonians (now roughly 70% of the total, up from 60% in 1990) and Russophones, largely descended from Soviet-era migrants attracted to industrial jobs and a higher standard of living than they could find in other Soviet republics like Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. See this

2007 post from Itching for Eestimaa for a decent overview of the situation. The two populations behave differently in many ways, including in demographic patterns. The three most populous counties fit into

three different categories, Harju being roughly 60% ethnically Estonian by population, Tartu ~85%, but Ida-Viru 20%. (Somewhat ethnically mixed up to the Soviet era, post-war displacement of ethnic Estonians and mass immigration to the northeast's industrial centres created the only one of Estonia's fifteen counties with a non-Estonian majority population.)

I've a draft of a much longer post hidden in the archives. Briefly, I would like to say that this all fits with my noting of with ethnic Estonians now inclining to a relatively Nordic pattern (relatively high fertility, significant postponement of births, very significant extramarital fertility) and Russophones behaving in the opposite manner. See Puur et al.'s brief abstract

"Fertility patterns among foreign-origin population: the evidence from Estonia" for an outline.

The analysis reveals a remarkably strong contribution of foreign-origin population to the total number of birth. In the 1970s and 1980s it accounted for more than a third of births registered in the country, leaving a long-term imprint on the ethnic and linguistic composition of the population. The cessation of massive inflow after the turn of the 1990s has somewhat reduced the proportion of births to women of immigrant background. In the recent years it has accounted for less than 30% of the total.

The comparison of completed cohort fertility rates allows to distinguish between two different patterns among women of immigrant origin born during the 20th century. In older cohorts, born in the first quarter of the century, the foreign origin population shows noticeably higher fertility, reflecting the later onset of fertility transition in the regions from which the immigrants originate. The progression of fertility transition in the latter resulted in the continuous decline and the convergence of levels with the native population in the birth cohorts of the late 1920s. However, the state of convergence proved temporary and in the generations born in the 1930s and later, the levels diverged again with foreign origin women having a systematically lower fertility compared to their native counterparts.

The examination of parity progression ratios and the ultimate parity distribution reveals that the lower completed fertility stems mainly from the less frequent progression to a second, and in particular, to a third birth among the foreign origin population. Compared to the native population, the corresponding measures have been twice or even more than twice lower, demonstrating the largest difference across parity distribution. On the other hand, the proportion of women with one-child has been markedly higher among immigrants. At the same time it is interesting to note that childbearing has typically occurred at an earlier age among the foreign-origin population.

Meanwhile, as Lars Agnarson notes in his paper

"Estonia’s health geography: West versus east – an ethnic approach", partly because of Russophone concentration in Soviet-era industry--exactly the sorts of industries which got hit by the post-Communist transition--Russophones evidence significantly higher mortality than their ethnic Estonian co-residents, mortality rates apparently rising in proportion to the homogeneity of Russophone communities. Between 2000 and 2009 the populations of ethnic Estonians and ethnic Russians

each decreased by roughly nine thousand, but the ethnic Russian population is less than 38% of the size of the ethnic Estonian.

What does this imply? For Estonia as a whole, last year's natural increase might indicate that Estonia is moving from a post-Communist demographic system (low fertility, high mortality) to a Nordic one characterized by relatively high subreplacement fertility, low mortality, and a post-modern approach to family relationships. The question of emigration is noteworthy, and over the 2000-2008 period Estonia does seem to have

seen the emigration of 13 thousand people. The volume of emigration has been significantly less than in Latvia or Lithuania, however, and much of it has been directed towards a Finland that is both geographically and culturally quite close to Estonia, Helsinki and Tallinn being separated by no more than a ferry ride. Much of what Estonian emigration has developed may be more temporary in nature. Estonian-Finnish migration is even

bidirectional: Estonia can offer job opportunities for Finnish workers, too, and the lower cost of living in Estonia compared to Finland may be a long-run advantage.

It's also worth noting that a relatively less dire demographic situation than that of neighbouring Latvia may well provide Estonia with if not advantages, fewer disadvantages--including economic ones--over its southern neighbour, and others, too.

Within Estonia, if the past two years' sustained difference between a relatively high fertility/low mortality ethnic Estonian population and a relatively low fertility/high mortality Russophone population remains, then the continued shrinkage and aging of the Russophone population is inevitable. This will have significant effects on everything from the spatial distribution of the Estonian population (what will happen in the northeast) and the futures of economic sectors depending heavily on Russophone labour to the balance of political power in Estonia and Estonian relations with its neighbours.

Expect more later, please; consider this a taster.