Showing posts with label regions. Show all posts

Showing posts with label regions. Show all posts

Thursday, December 18, 2014

On looking at peripheries

For the next little while here at Demography Matters, I'll be posting examinations of various lengths about the demographic dynamics of peripheries, territories and populations both. Part of my reason for this has to do with my own personal interests in the topic, coming from a relatively marginal area of Canada myself. Relationships between peoples and individuals and regions located in the core and periphery and semi-periphery, to borrow the language of world-systems theory, have always interested me, especially as these relationships change.

More of my interest has to do with the ways in which this division of the world is starting to have real consequences for population change. As the distribution of human and economic capital changes, becoming scarce in some parts of the world and more abundant in others, with some being united by borders and others being cut off, real tensions do develop. This is especially so where things change unevenly. What areas are winners? What areas might catch up? What areas might end up declining?

Stay tuned.

Labels:

demographics,

fertility,

migration,

prince edward island,

regions

Tuesday, March 12, 2013

A brief note on Bricker and Ibbitson's The Big Shift

Marginal Revolution's Tyler Cowen cited yesterday The Big Shift: The Seismic Change In Canadian Politics, Business, And Culture And What It Means For Our Future, by Canadians Darrell Bricker and John Ibbitson. Their thesis?

The political, media and business elites of Toronto, Ottawa and Montreal ran this country for almost its entire history. But in the last few years, they have lost their power, and most of them still do not realize it’s gone. The Laurentian Consensus, a name John Ibbitson coined for the dusty liberal elite, has been replaced by a new, powerful coalition based in the West and supported by immigrant voters in Ontario. So what happened?

Great global migrations have washed over Canada. Most people are unaware that the keystone economic and political drivers of this country are now Western Canada and the immigrants from China, India, and other Asian countries who increasingly are turning Ontario into a Pacific-oriented province. Those in politics and business have greatly underestimated how conservative these newcomers are, and how conservative they are making our country. Canada, with an ever-evolving and growing economy and a constantly changing demographic base, has become divorced from the traditions of its past and is moving in an entirely new direction.

In The Big Shift, John Ibbitson and Darrell Bricker argue that one of the world’s most consensual countries is polarizing, with the west versus the east, suburban versus urban, immigrants versus old school, coffee drinkers versus consumers of energy drinks. The winners—in politics, in business, in life—will figure out where the people are and go there too.

(The quote that caught Cowen's attention was a projection: "In Toronto, 63 percent of the population will be foreign born by 2031…In Vancouver, the foreign-born population will be 59 percent." That figure doesn't sound off.)

I haven't read the book, so I can't comment authoritatively. What I can say is that the thesis isn't obviously wrong. The Conservatives have had significant success in breaking the traditionally close relationship of the (in my opinion) slowly dying Liberal Party's support among recent immigrants, while the traditionally more centrist and left-wing central Canadian region has been relative decline as Alberta--as we've noted here for the past seven years--leads western Canada in experiencing very strong economic and population growth. My two May 2011 posts reacting to the 2011 election (1, 2) could be read as suggesting some sort of ideological polarization of the country between a Conservative-leaning west and a NDP-leaning centre. At the very least the book seems worth a look.

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

On Tokyo's relative ascent in a shrinking Japan

Tuesday night is usually anime night for me and my friends, an evening when we watch some of the high-quality animated series that have made it out of Japan into North American audiences. A trope I've noticed appear frequently in anime is that of the vast city, of immense urban sprawl that dominates life. Taking a look at the statistics, Japan certainly is a highly urbanized society, not only in the simple terms of Japan being a country where more than 90% of the population lives in cities but in the reality that the Greater Tokyo Area--the conurbation dominated by Tokyo but including all seven prefectures of the Kantō region and Yamanashi Prefecture to the west--is still by many measurements the largest conurbation in the world.

Recently, Wendell Cox at his New Geography site has been producing interesting posts about, among other things, the future of Tokyo.. In September, Cox linked to a prediction of significant aging and population shrinkage in Tokyo over the 21st century.

2100 will see Tokyo's population standing at around 7.13 million — about half of what it is today — with 45.9 percent of those in the metropolis aged 65 or over, a group of academics and bureaucrats has concluded.

Tokyo's population, which stood at 13.16 million in 2010, will peak at 13.35 million in 2020 before dropping by 45.8 percent from the 2010 census figure 88 years from now, the group, including seven academics and 10 metro government and municipal bureaucrats, said Sunday.

This means the 2100 population will be resemble that of 1940's Japan, before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

"The number of people in their most productive years will decline, while local governments will face severe financial strains," the group said in a statement. "So it will be crucial to take measures to turn around the falling birthrate and enhance social security measures for the elderly."

The number of Tokyoites 65 or over, estimated at 2.68 million in 2010, will peak at 4.41 million in 2050 before falling to 3.27 million in 2100, while their presence in the overall population will rise to 37.6 percent in 2050 and 45.9 percent in 2100 compared with 20.4 percent in 2010.

Those aged in their productive years between 15 and 64 will represent 46.5 percent of the population in 2100, the group said.

The projections assume that people moving to Tokyo continue to outnumber those moving out and that the fertility rate — the average number of children a woman gives birth to over her lifetime — will remain unchanged at its 2010 level of 1.12 among Tokyo women, the lowest in the nation.

This prediction, long-range though it might be, doesn't strike me as entirely unlikely, on account of the longevity of the Japanese population, sustained low fertility rates, and low rates of immigration. (Comparing Tokyo with Seoul is salutary.) Tokyo was plausibly selected by the Still City interdisciplinary study group as the paradigmatic post-growth city, stagnant demographically, economically, and politically.

That said, as noted by Cox in June in his survey of Tokyo's demographics, Tokyo's demographics are actually substantially healthier than those of the remainder of Japan on account of Tokyo's attractiveness to migrants from elsewhere in Japan, to the point that Tokyo's relative demographic weight is only going to grow.

Japan has been centralizing for decades, principally as rural citizens have moved to the largest metropolitan areas. Since 1950, Tokyo has routinely attracted much more than its proportionate share of population growth. In the last two census periods, all Japan’s growth has been in the Tokyo metropolitan area as national population growth has stagnated. Between 2000 and 2005, the Tokyo region added 1.1 million new residents, while the rest of the nation lost 200,000 residents. The imbalance became even starker between 2005 and 2010, as Tokyo added 1.1 million new residents, while the rest of the nation lost 900,000.

Eventually, Japan’s imploding population will finally impact Tokyo. Population projections indicate that between 2010 and 2035, Tokyo will start losing population. But Tokyo's loss, at 2.1 million, would be a small fraction of the 16.5 million loss projected for the rest of the nation (Figure 5). If that occurs, Tokyo will account for 30 percent of Japan's population, compared to 16 percent in 1950. With Japan's rock-bottom fertility rate, a declining Tokyo will dominate an even larger share of the country’s declining population and economy in the coming decades.

In the post "Japan’s 2010 Census: Moving to Tokyo", Cox noted that the Greater Tokyo Area's growth is exceptional, that even the Keihanshin conurbation anchored by Osaka, Kobe, and Kyoto is declining. The decline of the only urban area comparable in size to the Greater Tokyo Area leaves the country's urban hierarchy all the more focused on the national capital.

The fortunes of the prefectures in Japan's two largest urban areas could hardly be more different. The four prefectures of the Tokyo – Yokohama area had added approximately 3,000,000 people in each five-year period until 1975. Since that time, growth has been slower, but the area has added 1 million or more people each five years from 1975 to 2010. On the other hand, the Osaka – Kobe – Kyoto area (Osaka, Hyogo, Kyoto and Nara prefectures), which also experienced strong growth after World War II, adding between one and two million people in each five year period until 1975, has seen its growth come to a virtual standstill. Over the past five years, Osaka – Kobe – Kyoto added only 12,000 people. As a result, Osaka – Kobe – Kyoto is easily the slowest growing mega-city in the world, by far. Osaka – Kobe – Kyoto seems destined to fall substantially in world urban area rankings in the years to come. Tokyo – Yokohama, however, remains at least 14 million larger than any other urban area in the world, a margin that seems likely to be secure for decades to come.

[. . .] These numbers suggest there is ample reason to worry about the concentration of population and power in the Tokyo – Yokohama area, which now contains nearly 30 percent of the nation's population. None of the world's largest nations, outside of Korea (which ranks 25th in population), are so concentrated in one urban area. Among other nations with more than 100 million the greatest concentration is in Mexico, where Mexico City accounts for less than 20 percent of the population. The largest urban areas in Brazil (Sao Paulo) and Russia (Moscow) have little more than 10 percent of the population. The largest urban area in the United States, New York, accounts for less than seven percent of the population, while in China (Shanghai) and India (Delhi), the largest urban areas house less than two percent of the population. Paris, the beneficiary of centuries of centralization, has less than 20 percent of the population.

(This sort of super-centralization isn't unique--as I noted in November 2010, half the population of South Korea lives in greater Seoul.)

What might this mean for Japan? I'd question whether there's any particular sense in Japan trying to reverse the centralization of its population in Tokyo, actually. Where will it get the funds necessary to subsidize outlying areas, like the Tohoku I surveyed back in March 2011, which has been experiencing first relative then absolute decline for generations? Seeking Alpha's observation that Japan's new trade deficit and shrinking savings leaves the country short on cash is quite valid. Can Japan afford to prop up its peripheries if the people living in these peripheries no longer want to live there?

Wednesday, May 30, 2012

On the aging of the Canadian population

The big news today from Statistics Canada is that Canadian population ageing continues.

The number of seniors aged 65 and over increased 14.1% between 2006 and 2011. This rate of growth was more than double the 5.9% increase for the Canadian population as a whole. It was also higher than the rate of growth of children aged 14 and under (+0.5%) and people aged 15 to 64 (+5.7%).

As a result, the number of seniors has continued to converge with the number of children in Canada between 2006 and 2011. The census counted 5,607,345 children aged 14 and under, compared with 4,945,060 seniors. In the working-age population, the census counted 22,924,300 people.

The main factors behind the aging of Canada's population are the nation's below-replacement-level fertility rate over the last 40 years and an increasing life expectancy. Canada's working-age population is also growing older.

Within the working-age group, 42.4% of people were aged between 45 and 64, a record high proportion. This was well above the proportion of 28.6% in 1991, when the first baby boomers reached age 45.

[. . .]

In 2001, for every person aged 55 to 64, there were 1.40 people in the age group 15 to 24. By 2011, this ratio had fallen slightly below 1 (0.99) for the first time. This means that for each person leaving the working-age group in 2011, there was about one person entering it.

A second report highlights the regional divides in Canada, with relatively more rapid aging in Atlantic Canada and Québec than the Canadian average, while Alberta and British Columbia (largely owing to substantial migration, both from the rest of Canada and internationally) and the territories (largely owing to high birth rates) have resisted this tendency somewhat. Rural Canada, too, taken as a bloc, is experiencing faster aging than urban Canadian centers.

The number of seniors aged 65 and over increased 14.1% between 2006 and 2011. This rate of growth was more than double the 5.9% increase for the Canadian population as a whole. It was also higher than the rate of growth of children aged 14 and under (+0.5%) and people aged 15 to 64 (+5.7%).

As a result, the number of seniors has continued to converge with the number of children in Canada between 2006 and 2011. The census counted 5,607,345 children aged 14 and under, compared with 4,945,060 seniors. In the working-age population, the census counted 22,924,300 people.

The main factors behind the aging of Canada's population are the nation's below-replacement-level fertility rate over the last 40 years and an increasing life expectancy. Canada's working-age population is also growing older.

Within the working-age group, 42.4% of people were aged between 45 and 64, a record high proportion. This was well above the proportion of 28.6% in 1991, when the first baby boomers reached age 45.

[. . .]

In 2001, for every person aged 55 to 64, there were 1.40 people in the age group 15 to 24. By 2011, this ratio had fallen slightly below 1 (0.99) for the first time. This means that for each person leaving the working-age group in 2011, there was about one person entering it.

A second report highlights the regional divides in Canada, with relatively more rapid aging in Atlantic Canada and Québec than the Canadian average, while Alberta and British Columbia (largely owing to substantial migration, both from the rest of Canada and internationally) and the territories (largely owing to high birth rates) have resisted this tendency somewhat. Rural Canada, too, taken as a bloc, is experiencing faster aging than urban Canadian centers.

Sunday, May 08, 2011

How demographics shaped the 2011 Canadian federal election

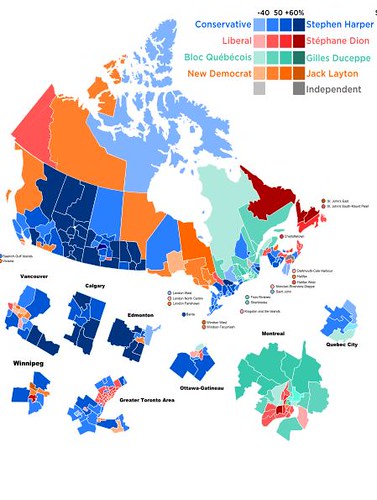

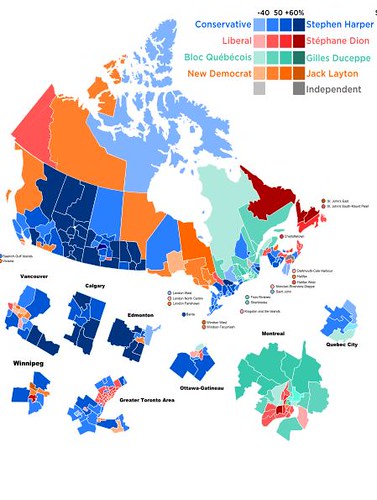

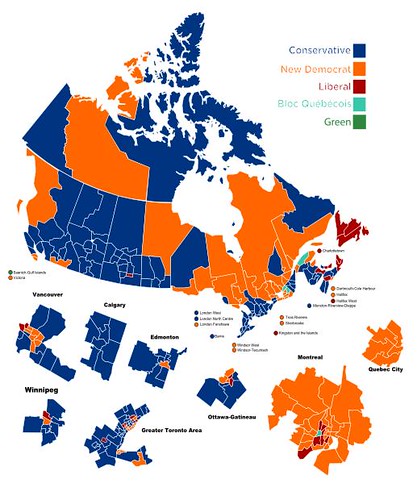

My previous post here touched upon the remarkable consequences of the Canadian federal election held last Monday. The New Democratic Party made massive breakthroughs, especially in Québec, to become the official opposition, while the separatist Bloc Québécois was devastated (from 47 to 4 seats) and the Liberal Party was more than halved. Maps do a good job of illustrating this transformation. Copied from here, this map shows the distribution of seats following the 2008 federal election in Canada. Blue is for the Conservatives, red for the Liberals, orange for the New Democratic Party, and teal for the Bloc Québécois.

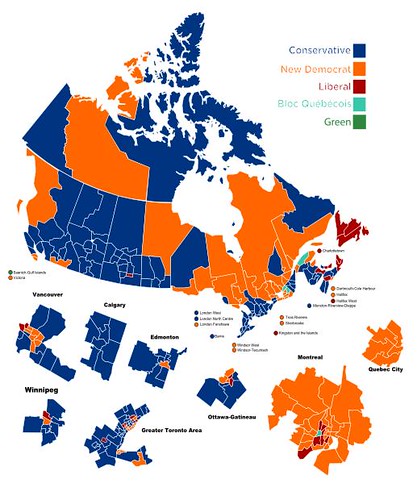

Here is a map showing the results of the 2011 election.

Population changes played a major role in this outcome. Take voter turnout, which rose 2.3% from 59.1% in 2008 to 61.4% this time. The low voter turnout is a major concern for Canadians, but so far no one has come up with a solution. Disenchantment with politics is pervasive.

The NDP made massive gains, going from 36 to 108 seats (by comparison, the previous peak was 43 seats in 1988). Many established parties were displaced. My own downtown Toronto riding of Davenport, represented by Liberal parliamentarians since 1962, switched massively over to the New Democratic Party, the NDP candidate outpolling the Liberal incumbent by 2:1. Davenport, with a large Portuguese-Canadian community, has traditionally voted Liberal. Why the change?

The Davenport riding is in transition. As Portuguese-Canadians become prosperous and move to the suburbs, the gentrification that has taken over The Annex neighbourhood is spreading west into Davenport. Since I've moved here, a townhouse complex has been built on the other side of the street, while an artists' community centre is by the laundry and any number of old storefronts about being converted into residential units.

It may not be that whereas Liberal Mario Silva made his name partly through his aid to immigrants, the NDP's Andrew Cash first came to attention as a punk rocker, then as a journalist for the alternative press. And yes, you probably won't be surprised to hear that I voted NDP myself. I was frustrated with the Liberal Party and wanted a change. Clearly, I was not alone.

One very notable instance of demographics on the election--here, the tendency of Québec to vote as a bloc and to swing massively from one party to another was the massive success enjoyed by the NDP, which crushed the Bloc Québécois and won 58 of the province's 75 seats. By way of comparison, before the election the NDP had only one seat in Québec, in Montréal. Québécois seem to have tired of the Bloc, and voted for the only other party in massive numbers. The NDP didn't have to try: one candidate, a unilingual Anglophone who spent a good part of the campaign in Las Vegas on vacation and hasn't even visited her rising beat a 13 years' incumbent.

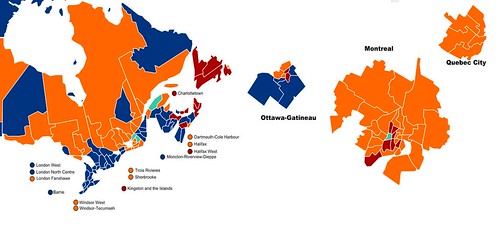

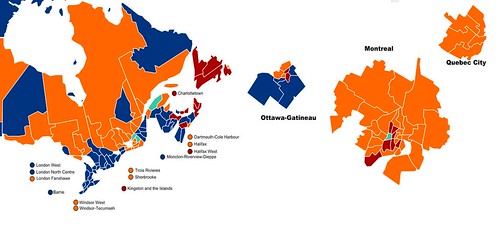

What's very interesting about this is that the NDP is now the dominant party of French Canada, not just Québec. I wrote earlier here about the substantial assimilation facing most Francophone populations outside of Québec, but for the time being there are close to a million Francophones in adjacent Ontario and New Brunswick. These populations also voted substantially for the NDP. Taken from Wikimedia here, the below is an edited map showing electoral outcomes in central and eastern Canada, with maps of outcomes in the three Canadian cities with the largest Francophone populations (in descending order, Montréal, Québec City, and Ottawa-Gatineau) added.

Even Francophone neighbourhoods in Ottawa voted for the NDP.

What this means, given the weakness of the governing Conservatives in the province, is that the NDP is the only political party to have large numbers of members in both French Canada and English Canada. If the party can assimilate its new huge cohort, this straddling the language frontier could well make it an inevitable party of government.

Finally, here in Toronto the Conservatives pierced what was once a Liberal stronghold and split the city with the NDP. The first map below shows the situation before the election; the second shows the situation after the election.

![20081014_GTA_results[1]](http://farm6.static.flickr.com/5141/5684385345_c90b9eb30f.jpg)

![201152-2011-GTA-ridings[1]](http://farm6.static.flickr.com/5064/5684385239_773fff858a.jpg)

This division corresponds substantially to the geographical divisions manifested in Toronto's recent mayoral election, where the left-wing George Smitherman held the downtown but the right-wing Rob Ford carried the day with the outer peripheries of the city: as described by the "Three Torontos" paradigm, poorer, more multiethnic, and with more problems about a left-leaning city government that didn't seem to do much for them. These areas traditionally voted Liberal federally--for instance, the Portuguese Canadians--because the Liberal Party is the one responsible for the lifting of discriminatory immigration legislation and the introduction of multicultural policies in the 1970s. As immigrant communities have become larger and more stable, and the Conservative Party has made efforts to appeal through social and economic conservatism, many of their members have switched allegiances to the Conservative Party. While a good marker of assimilation, this is not good for the Liberals.

What does all this mean? Considering the Conservative Party's gains in Ontario, and the NDP's massive success in Québec and substantial improvement in the rest of Canada, the future of the Liberal Party as a potential party of government is in doubt. Without any particularly coherent geographic or communal base and no longer the party of central Canada's cities (and patches elsewhere), how can it succeed? As for Québec, the effective destruction of the Bloc Québécois and the defection of Québécois voters en masse to the federalist NDP may signal significant reverses for the local separatist movement.

It is exciting times for Canadian politics. Demographics both established and changing can be thanked for a good chunk of it.

Here is a map showing the results of the 2011 election.

Population changes played a major role in this outcome. Take voter turnout, which rose 2.3% from 59.1% in 2008 to 61.4% this time. The low voter turnout is a major concern for Canadians, but so far no one has come up with a solution. Disenchantment with politics is pervasive.

The NDP made massive gains, going from 36 to 108 seats (by comparison, the previous peak was 43 seats in 1988). Many established parties were displaced. My own downtown Toronto riding of Davenport, represented by Liberal parliamentarians since 1962, switched massively over to the New Democratic Party, the NDP candidate outpolling the Liberal incumbent by 2:1. Davenport, with a large Portuguese-Canadian community, has traditionally voted Liberal. Why the change?

The Davenport riding is in transition. As Portuguese-Canadians become prosperous and move to the suburbs, the gentrification that has taken over The Annex neighbourhood is spreading west into Davenport. Since I've moved here, a townhouse complex has been built on the other side of the street, while an artists' community centre is by the laundry and any number of old storefronts about being converted into residential units.

It may not be that whereas Liberal Mario Silva made his name partly through his aid to immigrants, the NDP's Andrew Cash first came to attention as a punk rocker, then as a journalist for the alternative press. And yes, you probably won't be surprised to hear that I voted NDP myself. I was frustrated with the Liberal Party and wanted a change. Clearly, I was not alone.

One very notable instance of demographics on the election--here, the tendency of Québec to vote as a bloc and to swing massively from one party to another was the massive success enjoyed by the NDP, which crushed the Bloc Québécois and won 58 of the province's 75 seats. By way of comparison, before the election the NDP had only one seat in Québec, in Montréal. Québécois seem to have tired of the Bloc, and voted for the only other party in massive numbers. The NDP didn't have to try: one candidate, a unilingual Anglophone who spent a good part of the campaign in Las Vegas on vacation and hasn't even visited her rising beat a 13 years' incumbent.

What's very interesting about this is that the NDP is now the dominant party of French Canada, not just Québec. I wrote earlier here about the substantial assimilation facing most Francophone populations outside of Québec, but for the time being there are close to a million Francophones in adjacent Ontario and New Brunswick. These populations also voted substantially for the NDP. Taken from Wikimedia here, the below is an edited map showing electoral outcomes in central and eastern Canada, with maps of outcomes in the three Canadian cities with the largest Francophone populations (in descending order, Montréal, Québec City, and Ottawa-Gatineau) added.

Even Francophone neighbourhoods in Ottawa voted for the NDP.

What this means, given the weakness of the governing Conservatives in the province, is that the NDP is the only political party to have large numbers of members in both French Canada and English Canada. If the party can assimilate its new huge cohort, this straddling the language frontier could well make it an inevitable party of government.

Finally, here in Toronto the Conservatives pierced what was once a Liberal stronghold and split the city with the NDP. The first map below shows the situation before the election; the second shows the situation after the election.

![20081014_GTA_results[1]](http://farm6.static.flickr.com/5141/5684385345_c90b9eb30f.jpg)

![201152-2011-GTA-ridings[1]](http://farm6.static.flickr.com/5064/5684385239_773fff858a.jpg)

This division corresponds substantially to the geographical divisions manifested in Toronto's recent mayoral election, where the left-wing George Smitherman held the downtown but the right-wing Rob Ford carried the day with the outer peripheries of the city: as described by the "Three Torontos" paradigm, poorer, more multiethnic, and with more problems about a left-leaning city government that didn't seem to do much for them. These areas traditionally voted Liberal federally--for instance, the Portuguese Canadians--because the Liberal Party is the one responsible for the lifting of discriminatory immigration legislation and the introduction of multicultural policies in the 1970s. As immigrant communities have become larger and more stable, and the Conservative Party has made efforts to appeal through social and economic conservatism, many of their members have switched allegiances to the Conservative Party. While a good marker of assimilation, this is not good for the Liberals.

What does all this mean? Considering the Conservative Party's gains in Ontario, and the NDP's massive success in Québec and substantial improvement in the rest of Canada, the future of the Liberal Party as a potential party of government is in doubt. Without any particularly coherent geographic or communal base and no longer the party of central Canada's cities (and patches elsewhere), how can it succeed? As for Québec, the effective destruction of the Bloc Québécois and the defection of Québécois voters en masse to the federalist NDP may signal significant reverses for the local separatist movement.

It is exciting times for Canadian politics. Demographics both established and changing can be thanked for a good chunk of it.

Labels:

canada,

french canada,

immigration,

québec,

regions

Thursday, April 07, 2011

How migration contributed to the meltdown in Côte d'Ivoire

The civil war in the West African country of Côte d'Ivoire is entering its final stages (I hope).

This conflict has its roots in the country's demographics, particularly in its immigrant population. Landinfo's Geir Skogseth has a extensive chronology of the crisis and its background. The migration from the Sahel to the West African coast that I blogged about back in June 2006 was one of the most important theme in Ivoirien demographic change.

Sadly for Côte d'Ivoire, the strong post-independence economic growth that attracted these millions of migrants disappeared by the 1980s, and in the democratic transition following the death of Houphouët-Boigny, ethnic nationalism via the concept of Ivoirité took hold.

The only virtue that this conflict has is that if Gbagbo is decisively defeated, Côte d'Ivoire might be able to move beyond its sterile north-south conflict and evolve in a positive direction. This, alas, might be a lost cause, with Ivoirité having caught on. In the meantime, as the Inter Press Service's Fulgence Zamblé noted, the Côte d'Ivoire that was once a magnet for migrants from across West Africa has now become a major contributor to refugee flows within West Africa.

Forces loyal to Ivory Coast presidential claimant Alassane Ouattara laid siege to incumbent leader Laurent Gbagbo's residence on Thursday, after an attempt to pluck him from his bunker met with fierce resistance.

Fighting continued in the economic capital Abidjan as Ouattara's forces tried to unseat Gbagbo, who has refused to cede power after losing a November election to Ouattara according to U.N.-certified results.

Sporadic explosions broke the silence in one of the lighter nights of fighting since Ouattara's soldiers arrived in the city a week ago, a Reuters witness said.

A Gbagbo advisor based in Paris told Reuters Ouattara forces had renewed an assault on Gbagbo's residence late on Wednesday with support from U.N. and French helicopters. His statement could not be independently verified.

Ouattara forces had attempted to storm the residence in the upscale Cocody neighborhood earlier on Wednesday after talks led by the United Nations and France to secure Gbagbo's departure failed, but they were pushed back by heavy weapons fire, a western diplomatic source who lives nearby said.

[. . .]

Analysts said Ouattara forces, who swept south last week in a lightly contested march toward Abidjan, could struggle to best Gbagbo's remaining presidential guard and militias.

"Just like in Libya, it's going to take both the rebels and outside forces to push Gbagbo out," said Sebastian Spio-Garbrah, analyst at DaMina Advisors in New York.

This conflict has its roots in the country's demographics, particularly in its immigrant population. Landinfo's Geir Skogseth has a extensive chronology of the crisis and its background. The migration from the Sahel to the West African coast that I blogged about back in June 2006 was one of the most important theme in Ivoirien demographic change.

During the French colonisation, new migration patterns evolved due to the economic development of the southern part of the country. This led to two main migration flows:1. Urbanisation and rapid population growth in Abidjan fed by extensive migration from the whole country (as well as neighbouring countries – especially Burkina Faso, Mali and Guinea). Thus, Abidjan has grown from a tiny village to a city of more than three million in less than a century.

2. Expansion of the plantation economy in the south-western part of Côte d’Ivoire

led to the movement of large numbers of farmers from the north and southeastern

regions (as well as the neighbouring countries mentioned above –

especially Burkina Faso).

As is common all over Africa, several ethnic groups live across borders, and may be known under different names in different countries. For example, the Guéré/Wè are known as Krahn in Liberia, and the Yacouba/Dan are known as Gio.

The migrants going to Abidjan mainly work in commerce, transport, industry and as

artisans, whereas the migrants moving to the southwest mainly work in agriculture –

either as farmers or working on plantations. Most migrants from outside today’s Côte

d’Ivoire came from neighbouring French colonies – Burkina Faso was even

administered together with Côte d’Ivoire as a single entity. Comparatively few

migrants came from Liberia (independent in principle, but under strong American

influence) or from the British colony Gold Coast (Ghana since independence). The

migration to Côte d’Ivoire from other French colonies was encouraged by the French

authorities, and this policy was continued by president Houphouët-Boigny after

independence.

People with Kwa origin, especially Baoulé, were given preference in the colonial

administration, the bureaucracy and in the plantation economy, and this situation

continued after independence. A smaller migration flow in numbers, but with great

political importance, consisted of educated Baoulé and other southerners who moved

from the southeast to other parts of the country to take up administrative posts – in

the educational system, as civil servants and as administrative staff on plantations.

As mentioned above, the migration from outside Côte d’Ivoire has been substantial,

and roughly a quarter of the population of Côte d’Ivoire are people with origin in

neighbouring countries. Relatively few of these migrants have been naturalised, not

the least since this generally was a non-issue until the end of the 1980s. Only then

did a serious debate evolve on whether there should be a difference in rights between

Ivorian citizens and others living in the country. During the colonial period and the

single-party system under president Houphouët-Boigny, there was no difference in

rights to speak of between Ivorian citizens and immigrants, accordingly immigrants

had little incentive to apply for naturalisation, and very few did.

Sadly for Côte d'Ivoire, the strong post-independence economic growth that attracted these millions of migrants disappeared by the 1980s, and in the democratic transition following the death of Houphouët-Boigny, ethnic nationalism via the concept of Ivoirité took hold.

One key to exacerbating ethnic divisions here is the concept of Ivoirité, which means the state of being a true Ivorian. The term manifests itself throughout all levels of society, and is held up by many observers as a root cause of the country's violent downward spiral from its status throughout the 1970s and '80s as the most prosperous, stable country in volatile West Africa.

Many residents from the government- controlled southern part of country say those from the rebel-held north (often identifiable by their names) are not true Ivorians because many have lineage originating in poorer, neighboring countries such as Mali or Burkina Faso. Some southerners also resent that their northern neighbors support northern political figures.

[. . .]

The Ivoirité concept emerged here in the 1970s when many nationals from neighboring countries flooded into southern Ivory Coast to work the manual labor jobs in the coffee and cocoa sectors. Many Ivorians became resentful, feeling the newcomers were coming to take advantage of the financial boom the country was experiencing.

In the 1990s, former President Henri Konan Bédié brought the term to the national stage when he used Ivoirité to gain an advantage over former Prime Minister Alassane Ouattara in the 1995 presidential election. He accused Mr. Ouattara, who is from the north, of not being 100-percent Ivorian.

Benoit Scheuer, a Belgian sociologist who made a documentary film called "Ivory Coast: The Identity Powder Keg" in 2001 in which he filmed acts of vandalism and physical violence stemming from Ivoirité, says it was the intellectuals around Mr. Bédié who brought Ivoirité back to into the picture. Mr. Scheuer compares Ivoirité to exclusionary tactics used in other conflicts such as Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia.

The country, he writes in an e-mail interview, has a "political elite that wants power or is in power but has a legitimacy problem (this was the case of [former President] Habyarimana in Rwanda and Bédié in Ivory Coast). In these cases, the elites are going to manipulate the spirit and the mentality [of the citizens] and are going to develop a discourse, a rhetoric of 'them and us.' "

The only virtue that this conflict has is that if Gbagbo is decisively defeated, Côte d'Ivoire might be able to move beyond its sterile north-south conflict and evolve in a positive direction. This, alas, might be a lost cause, with Ivoirité having caught on. In the meantime, as the Inter Press Service's Fulgence Zamblé noted, the Côte d'Ivoire that was once a magnet for migrants from across West Africa has now become a major contributor to refugee flows within West Africa.

As many as a million people have fled Côte d'Ivoire's commercial capital, Abidjan, due to intensified fighting. Many people are fleeing to areas in the north, centre and east of the country as thousands of youth answered a call to join forces loyal to Laurent Gbagbo; others are trying to leave the country.

Saturday saw a rally of up to 15,000 youth supporters of Gbagbo outside the presidential palace in Abidjan, but the exodus from the city began accelerating following a mortar attack on a market in the northern suburb of Abobo on Mar. 18, which killed 30 people,and wounded 60 more.

UNOCI, the U.N. peacekeeping force in Côte d'Ivoire, said the shelling of the market was carried out by soldiers loyal to Gbagbo, who has refused to concede that his rival, Alassane Ouattara, was the winner of presidential elections last November.

The death toll since mid-December is put at 462 by the United Nations, rising quickly as Gbagbo supporters and loyalist soldiers fight their way into areas of the city identified as Ouattara strongholds.

An estimated 100,000 people have sought refuge in camps and villages in Côte d'Ivoire's neighbour to the west, Liberia. The deteriorating situation will likely also see an increase in refugees fleeing east, across the border into Ghana.

Labels:

africa,

ethnicity,

regions,

war,

west africa

Saturday, March 26, 2011

"Set them free"

One theme that Burgh Diaspora has been exploring in its study of urban redevelopment is the likelihood that for residents of depressed areas--the blog focuses its attention on American cities, on places like Buffalo or better yet Detroit, where the census resulted revealed that the Motor City's population fell by a quarter over the past decade--emigration makes much more sense than staying. Ryan Avent's post at the Economist argues that trying to keep people from leaving isn't very clear-minded.

The problem, as Burgh Diaspora notes, is not only the question of how to regenerate a community when you combine necessary investments in cultural capital with geographical mobility, but the need of how to avoid the cheap fix of avoiding population decline not by making a city more attractive for a mobile population but by keeping populations simply locked in place. Not-dismal optics can't substitute for economic development, and in the long run won't discourage emigration but simply make the system more brittle: Look at East Germany after reunification. I like the conclusion here: "[T]he main point is important. Invest in people, not places. If a place is good at developing people, then it will be a desirable residence."

Also, here.

This applies to human communities on all scales: cities, regions, countries, continents even. This may be easier said than done, but it has to be said.

[N]ot every state can benefit from adding new people (nor should they). One panel featured two officials from the state of Michigan, which has suffered from a long period of decline and which continues to seek ways to right the ship. It would be possible, even easy, to resurrect Michigan. What would it take? Start with a special visa programme, in which skilled immigrants from other countries are offered easier visa terms and an expedited road to citizenship if they accept a visa that requires them to work in the Detroit area for five years. Follow that up by endowing a massive, DARPA-style energy research laboratory in the Detroit area. Set up special venture capital funds that offer excellent loan terms to start-ups connected with the lab or area universities, if they're willing to locate their new business in Michigan. Set up a special economic zone in southeastern Michigan that features an "invisible" border with Canada. Build high-speed rail lines from Detroit to Chicago and Toronto. Do all that, and I guarantee you that Detroit will be growing like mad in ten years. Honestly, even the visa programme alone might generate a turnaround.

The question is: to what end are we resurrecting Michigan? If the goal is to help the residents of Michigan, it would be much cheaper and easier to do so by investing in those individuals, in order to help them move to more successful local economies. Indeed, without investments in the people of Michigan, it's not clear how much a turnaround in the state's fortunes will benefit existing residents. Many have stayed in the state because they love the place, no doubt, but many others have not left because they're unprepared to find success in growth industries elsewhere. Moving the growth industries to their backyard won't change that fact.

If you're the governor of a declining state, you can't help but do everything you can to return your state to growth. But it's important to remember that the best thing for the American economy as a whole will often be for people to leave lagging areas.

The problem, as Burgh Diaspora notes, is not only the question of how to regenerate a community when you combine necessary investments in cultural capital with geographical mobility, but the need of how to avoid the cheap fix of avoiding population decline not by making a city more attractive for a mobile population but by keeping populations simply locked in place. Not-dismal optics can't substitute for economic development, and in the long run won't discourage emigration but simply make the system more brittle: Look at East Germany after reunification. I like the conclusion here: "[T]he main point is important. Invest in people, not places. If a place is good at developing people, then it will be a desirable residence."

Also, here.

For some, the climate or the built environment is more important. Both variables influence migration. However, most people will tolerate bad weather, a high cost of living, and an ugly built environment if it translates into personal or familial development. Migration is still primarily a matter of economics.

What Glaeser doesn't mention is that leaving Buffalo is more advantageous for the individual than staying, controlling for educational attainment. Increasing geographic mobility promotes economic development. Rural communities committing civic suicide understand this. Policymakers need to catch up.

This applies to human communities on all scales: cities, regions, countries, continents even. This may be easier said than done, but it has to be said.

Labels:

cities,

germany,

labour market,

migration,

regions,

united states

Wednesday, March 23, 2011

A profile of Tōhoku

I'd like to start by reiterating the point of Edward's post Sunday, about the likelihood of the earthquake triggering systemic changes in Japan. Certainly the recovery process will be long: Bloomberg's Shamin Adam suggests, after the World Bank, that it might take five years for Japan to finish rebuilding.

My take? Curiously and quite unexpectedly, I learned that the afflicted region of Tōhoku in northern Honshu hosts--shades of the Taiwanese village of Houtong--a cat-loving island community. The first paragraphs of Wikipedia's article on Tashirojima suggest interesting parallels with Houtong. The two communities, it seems, are economically marginal with the decline of their previous extractive industries and facing rapidly population decline and aging, while cats are among the most famously enduring invasive species. When the people go, the cats remain.

Tōhoku, a six prefecture region, has always been marginal, a relatively late addition to the Japanese ecumene.

Tōhoku was the last stronghold of the Emishi, a non-Japanese people linked to the pre-Yamato hunter-gatherer Jomon culture but eventually conquered and apparently assimilated by the 9th century CE. An interpretation of one recent DNA study of different regional populations in Japan might confirm that the Emishi left descendants in the current population of Tōhoku, noted as containing relatively fewer Yamato migrants than populations in western Japan. (Might.) Distant from the main centres of population and resources in western Japan, Tōhoku remained something of a frontier for a long time. In terms of the inhabitants' spoken language, for instance, the people were mocked for their thick dialect within Japan and without, the lower and deviant status of the Tōhoku dialect remaining still. Apparently the rustic character of Hagrid in the Harry Potter series has his speech rendered in Tōhoku dialect.

Tōhoku has become increasingly marginalized within Japan, in terns of its relative heft. Proof of this is easy enough to come by, since most of Tōhoku is included in the historical unit of Mutsu Province, which gathered together what is now the prefectures of Aomori, Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima along with two municipalities in the Sea of Japan-facing Akita Prefecture (Kazuno and Kosaka). (These last two municipalities, combined have a population a bit more than a half-percent of the four prefectures entirely in the former Mutsu.)

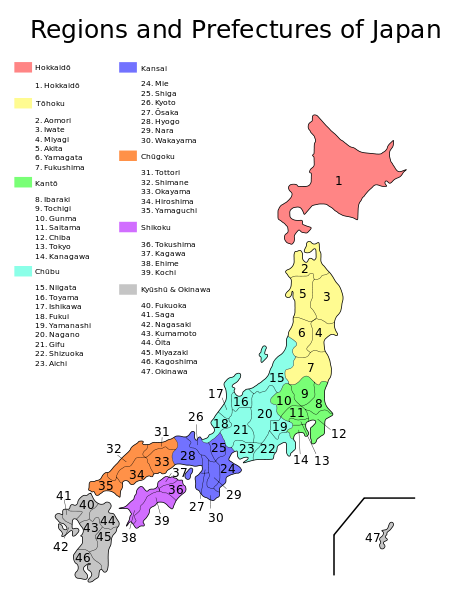

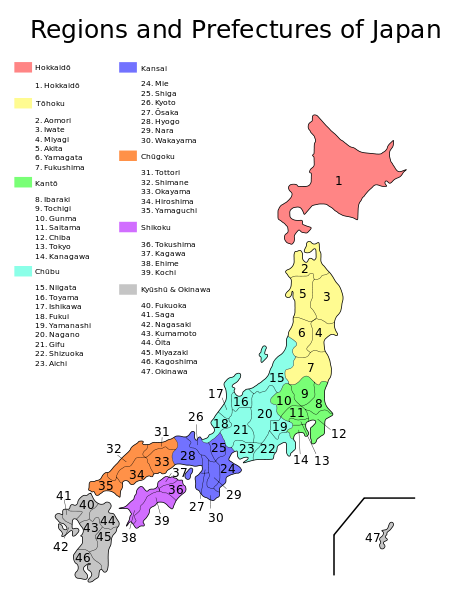

The region has under sustained relative, even absolute decline, for centuries. The most populous Japanese province at the beginning of the Shogunate, ranking behind only the Musashi province that included Tokyo, towards the end of the end of the Shogunate the two provinces switched positions. Mutsu suffered severely from famine-associated mortality crises in the mid-18th and early 19th centuries, its population falling absolutely and Mutsu's proportion of the Japanese population declining steadily from 7.5% in the 1721 population survey to 6.9% in the first Meiji census in 1873 census. The population of the Mutsu region did more than triple in the half-dozen generations to the 2010 survey, to reach 7.1 million in 2010, but its share of the total Japanese population slide further to 5.6% as of 2010. If not for the Meiji-era colonization of Hokkaido--up until the last quarter of the 19th century an island barely integrated into the Japanese political framework and populated by only a hundred thousand people--Tōhoku's gradual decline might have become that much more visible. As is, the region contains some of the least densely populated areas in the country, as Scott's map shows nicely.

This all brings us back to the question of the future of Japan. As a relatively rural and agricultural region, Tōhoku traditionally supported the Liberal Democratic Party, which whatever its other flaws at least continued to channel investments in local infrastructure. Scandals about misinvested funds and fundamental doubt helped Tōhoku transfer its loyalties to the Democratic Party.

One certain consequence of the disaster in Tōhoku is its destruction of the old order. Tashirojima might survive by dint of the tourism value of its cats, but how many of the small agricultural and fishing villages wrecked by the disaster will come back? Where will the money come from? Where will the people come from? Will even the regional metropole of Sendai regain its position relative to other Japanese cities less favoured by disaster? As Spike Japan's Richard Hendy pointed out, the devastation visiting not only on the Fukishima complex but on the other electric plants in eastern Japan, along with the region's power grid separate from western Japan's, means that Tōhoku--not to mention the rest of Japan--will be short of electricity, that most basic force of post-industrial civilization, for months if not years. As Charlie Stross noted in a separate post, the shortages of electricity ensure the premature deaths of thousands of vulnerable people deprived of air conditioning this summer, as far south as greater Tokyo.

Tōhoku doesn't have the resources to recover its pre-disaster levels. Japan likely doesn't have the resources necessary to let Tōhoku recover fully, and almost certainly lacks now and will continue to lack the interest in doing so given its other challenges. Tōhoku, I predict, has peaked: the long relative decline it began under the shoguns and continued through Meiji and the eventful 21st century will only accelerate, new reasons added to the many old for the decline of rural and marginal Japan that Hendy describes in his blog. The Japan Statistical Yearbook shows that the region's prefectures have been exporting people in large numbers for the past decade. Why will this slow down? Humans may be less resilient than cats, but then again, humans rightfully demand much more from their environment than their pets. Tashirojima's cats may well thrive long after Tashirojima's people have departed to whatever destination.

My take? Curiously and quite unexpectedly, I learned that the afflicted region of Tōhoku in northern Honshu hosts--shades of the Taiwanese village of Houtong--a cat-loving island community. The first paragraphs of Wikipedia's article on Tashirojima suggest interesting parallels with Houtong. The two communities, it seems, are economically marginal with the decline of their previous extractive industries and facing rapidly population decline and aging, while cats are among the most famously enduring invasive species. When the people go, the cats remain.

Tashirojima (田代島?) is a small island in Ishinomaki City, Miyagi Prefecture, Japan. It lies in the Pacific Ocean off the Oshika Peninsula, to the west of Ajishima. It is an inhabited island, although the population is quite small (around 100 people, down from around 1000 people in the 1950s). It has become known as "Cat Island" due to the large stray cat population that thrives as a result of the local belief that feeding cats will bring wealth and good fortune. The cat population is now larger than the human population on the island. (A 2009 article in Sankei News says that there are no pet dogs and it is basically prohibited to bring dogs onto the island.)

[. . .]

Since 83% of the population is classified as elderly, the island's villages have been designated as a "terminal villages" (限界集落) which means that with 50% or more of the population being over 65 years of age, the survival of the villages is threatened. The majority of the people who live on the island are involved either in fishing or hospitality.

Tōhoku, a six prefecture region, has always been marginal, a relatively late addition to the Japanese ecumene.

Tōhoku was the last stronghold of the Emishi, a non-Japanese people linked to the pre-Yamato hunter-gatherer Jomon culture but eventually conquered and apparently assimilated by the 9th century CE. An interpretation of one recent DNA study of different regional populations in Japan might confirm that the Emishi left descendants in the current population of Tōhoku, noted as containing relatively fewer Yamato migrants than populations in western Japan. (Might.) Distant from the main centres of population and resources in western Japan, Tōhoku remained something of a frontier for a long time. In terms of the inhabitants' spoken language, for instance, the people were mocked for their thick dialect within Japan and without, the lower and deviant status of the Tōhoku dialect remaining still. Apparently the rustic character of Hagrid in the Harry Potter series has his speech rendered in Tōhoku dialect.

Tōhoku has become increasingly marginalized within Japan, in terns of its relative heft. Proof of this is easy enough to come by, since most of Tōhoku is included in the historical unit of Mutsu Province, which gathered together what is now the prefectures of Aomori, Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima along with two municipalities in the Sea of Japan-facing Akita Prefecture (Kazuno and Kosaka). (These last two municipalities, combined have a population a bit more than a half-percent of the four prefectures entirely in the former Mutsu.)

The region has under sustained relative, even absolute decline, for centuries. The most populous Japanese province at the beginning of the Shogunate, ranking behind only the Musashi province that included Tokyo, towards the end of the end of the Shogunate the two provinces switched positions. Mutsu suffered severely from famine-associated mortality crises in the mid-18th and early 19th centuries, its population falling absolutely and Mutsu's proportion of the Japanese population declining steadily from 7.5% in the 1721 population survey to 6.9% in the first Meiji census in 1873 census. The population of the Mutsu region did more than triple in the half-dozen generations to the 2010 survey, to reach 7.1 million in 2010, but its share of the total Japanese population slide further to 5.6% as of 2010. If not for the Meiji-era colonization of Hokkaido--up until the last quarter of the 19th century an island barely integrated into the Japanese political framework and populated by only a hundred thousand people--Tōhoku's gradual decline might have become that much more visible. As is, the region contains some of the least densely populated areas in the country, as Scott's map shows nicely.

This all brings us back to the question of the future of Japan. As a relatively rural and agricultural region, Tōhoku traditionally supported the Liberal Democratic Party, which whatever its other flaws at least continued to channel investments in local infrastructure. Scandals about misinvested funds and fundamental doubt helped Tōhoku transfer its loyalties to the Democratic Party.

In Tohoku, the northern part of Japan’s biggest island, Honshu, and the home of Democrat founder and former leader Ichiro Ozawa, the beating was also fierce, if not quite as emphatic, as the LDP took 9 seats and the Democrats 26.

“Tohoku is generally conservative, with farmers supporting the LDP’s policies. But before the election their attitude had changed,” said Masaki Hara, a retired Sendai resident, who joined me watching results, along with many other captive ferry passengers, some of whom had lost interest in the Yomiuri Giants game on a competing TV screen.

Hara said citizens were questioning the value of big infrastructure projects, such as a subway line in Tohoku’s largest city of Sendai that had seen cost overruns, while doubting the Liberal Democratic Party’s vision.

“I don’t like Ozawa, but I support his taking on the LDP.”

One certain consequence of the disaster in Tōhoku is its destruction of the old order. Tashirojima might survive by dint of the tourism value of its cats, but how many of the small agricultural and fishing villages wrecked by the disaster will come back? Where will the money come from? Where will the people come from? Will even the regional metropole of Sendai regain its position relative to other Japanese cities less favoured by disaster? As Spike Japan's Richard Hendy pointed out, the devastation visiting not only on the Fukishima complex but on the other electric plants in eastern Japan, along with the region's power grid separate from western Japan's, means that Tōhoku--not to mention the rest of Japan--will be short of electricity, that most basic force of post-industrial civilization, for months if not years. As Charlie Stross noted in a separate post, the shortages of electricity ensure the premature deaths of thousands of vulnerable people deprived of air conditioning this summer, as far south as greater Tokyo.

Tōhoku doesn't have the resources to recover its pre-disaster levels. Japan likely doesn't have the resources necessary to let Tōhoku recover fully, and almost certainly lacks now and will continue to lack the interest in doing so given its other challenges. Tōhoku, I predict, has peaked: the long relative decline it began under the shoguns and continued through Meiji and the eventful 21st century will only accelerate, new reasons added to the many old for the decline of rural and marginal Japan that Hendy describes in his blog. The Japan Statistical Yearbook shows that the region's prefectures have been exporting people in large numbers for the past decade. Why will this slow down? Humans may be less resilient than cats, but then again, humans rightfully demand much more from their environment than their pets. Tashirojima's cats may well thrive long after Tashirojima's people have departed to whatever destination.

Labels:

animals,

economics,

first nations,

japan,

regions

Monday, December 27, 2010

On Spike Japan

Spike Japan, maintained by Tokyo blogger Richard Hendy, is one of the more interesting blogs out there, certainly among the more original blogs taking a look at the intersection of demographics with economics. Documenting his travels to areas of Japan outside of metropoli like Tokyo in acute essays and well-chosen photos, places that are slowly (or quickly) falling apart owing to a combination of two decades of slow-to-no economic growth and ever accelerating depopulation, Hendy got some international attention via this article from The Guardian written by Chris Michael earlier. How did he start? He describes Spike Japan's genesis in his introductory essay "Down the benjo: The ruin/nation of Japan".

Hendy has visited rural areas and small cities, two stand-out travelogues being his extended exploration of the northernmost and most recently settled major island of Hokkaido, and his recent sojourn to the

Amakusa islands off the west coast of Kyushu. Whether in Hokkaido, Amakusa, or elsewhere, the regions of Japan that Hendy visits are all areas located away from its prosperous industrial and urban centres, substantially rural, blighted economically and scenically by Bubble-era constructions, lacking in innovative local enterprises, heavily indebted, and sharing in the general drain of the young to the cities. After the recent financial crisis, the prospects that these regions might receive the investment that might turn things around--making them destinations for retirees, say--are trivial. The dream of a return to the land is ridiculous.

The thing is, what's happening to rural and marginal Japan is going to happen to urban and core Japan sooner or later. Trend economic growth, as Hendy observes, is inexorably trending downwards towards nothing, as the workforce continues to contract, the dependency ratio tips crazily, productivity stagnates and foreign competition grows and infrastructure ages.

Japan might be an extreme case, not least because of its lack of immigration--South Korea has become much more of an immmigrant country in a shorter period of time--but it's certainly not the only global economic power out there with lowest-low fertility. There's Germany, say, and certainly the various descriptions of the former East Germany's rapid population aging and shrinkage doesn't sound out of kilter with what Hendy has been writing about and photographing.

Spike Japan is one of those blogs that works on two different levels, as a personal travelogue and as an extended meditation on the existential economic problems of post-growth societies. Visit it for both of these reasons.

It may come as a shock to almost all of you living outside of Japan, and to some of you living in the center of its big cities, that as we approach the summer of 2009, swathes of the country are in ruins. It came as a shock to me, too, I have to confess, having lived for almost all of the last decade in the bubble of central Tokyo and only venturing outside occasionally to get to the airport, nearby beaches, and old friends in the mountains.

As the financial results came in for Japanese companies for the last quarter of 2008, in late January and early February, they were suggestive of a complete cessation of activity in certain sectors of the economy. My interest in what happened outside of the bubble I live in was only really piqued, though, by a report in the Financial Times that many of the Brazilian emigrants to Oizumi, the town in Japan with the highest percentage of such residents, were ready to pack for Sao Paolo. I went out to investigate and was fascinated and amazed by the combination of immigration, industry, bleakness, and normality. A series of e-mails I had anyway been writing to a friend gained traction from this visit, and developed into a series titled “Down the benjo”; “benjo” is a no longer particularly polite Japanese word for “bog” or “john”. I owe inspiration for the title from a reference early in the year by Willem Buiter, Professor of European Political Economy at the London School of Economics, on his maverecon blog at the Financial Times, to the Icelandic economy having been flushed “down the snyrting”. Much the same, it struck me when I read his post back in January, was happening to the Japanese economy.

The visit to Oizumi led to another, this time to Hitachi, the home of the multinational conglomerate of the same name, which prompted a longer e-mail essay, which in turn prompted a ramble down a recently abandoned railway line less than an hour from Tokyo, which resulted in a 15,000-word essay that took the best part of a month of free time to put together.

Hendy has visited rural areas and small cities, two stand-out travelogues being his extended exploration of the northernmost and most recently settled major island of Hokkaido, and his recent sojourn to the

Amakusa islands off the west coast of Kyushu. Whether in Hokkaido, Amakusa, or elsewhere, the regions of Japan that Hendy visits are all areas located away from its prosperous industrial and urban centres, substantially rural, blighted economically and scenically by Bubble-era constructions, lacking in innovative local enterprises, heavily indebted, and sharing in the general drain of the young to the cities. After the recent financial crisis, the prospects that these regions might receive the investment that might turn things around--making them destinations for retirees, say--are trivial. The dream of a return to the land is ridiculous.

According to the Rural Depopulation Research Association, "There are probably a lot of people who would like to move to the countryside if the conditions were right, (but) it's difficult to see how the number could increase with the present situation. The local communities need to maximize their areas' resources."

The "I-turn" movement (moving from the city to the country) and the "U-turn" movement (people from the country heading to the city, then back again) have been around since the 1980s. However, the things that discourage more young people from moving to the countryside are the same as ever.

"As things are," says Yuzawa. "Even if people want to go back the countryside, often there is nowhere for them to work and nowhere for them to live."

[. . .]

A survey by the Rural Depopulation Research Association in 2000 found that "company work" is the most popular choice for those that have already moved to the countryside. In other words, they avoid the shortage of work by commuting to the city. Relatively few work in the government construction industry, which plays a major part in the rural economy. Other U-turn and I-turn employment ranges from tourism to geriatric care to traditional crafts.

With the help of the help of the organization, local governments try and match jobs to candidates; but the right work isn't always available, and sometimes idealism isn't enough to persuade young people to give up city salaries.

But the Japanese country needs help from somewhere.

In a 2000 survey, more than a third of Japan's municipalities were classified as depopulated more than half Japan's land area. All had lost more than a quarter of their residents since the 1960s.

The thing is, what's happening to rural and marginal Japan is going to happen to urban and core Japan sooner or later. Trend economic growth, as Hendy observes, is inexorably trending downwards towards nothing, as the workforce continues to contract, the dependency ratio tips crazily, productivity stagnates and foreign competition grows and infrastructure ages.

It might just be, however, that despite recent evidence to the contrary, Japan has embarked on a vicious demographic spiral, in which a variety of complex feedback mechanisms set to work: aging results in declining international competitiveness, which results in greater economic hardship at home, which results in a suppressed birthrate; aging results in ballooning fiscal deficits, which in the absence of debt issuance must result in higher taxes or cuts to government spending, which cause economic pain, driving down the birthrate; aging, as the elderly dissave, results in a decline in the pool of domestic savings on which government borrowing is an implied claim, reducing room for fiscal maneuver and resulting in less ability to withstand exogenous shocks; aging further entrenches conservative attitudes to everything from pension reform to immigration, resulting in greater government outlays and smaller government receipts; aging leads the electorate to fear for the future of the pension system, resulting in more saving by the economically active, depressing consumption, which drives manufacturers offshore and raises unemployment, which is strongly correlated with the birthrate.

Japan might be an extreme case, not least because of its lack of immigration--South Korea has become much more of an immmigrant country in a shorter period of time--but it's certainly not the only global economic power out there with lowest-low fertility. There's Germany, say, and certainly the various descriptions of the former East Germany's rapid population aging and shrinkage doesn't sound out of kilter with what Hendy has been writing about and photographing.

Spike Japan is one of those blogs that works on two different levels, as a personal travelogue and as an extended meditation on the existential economic problems of post-growth societies. Visit it for both of these reasons.

Thursday, August 23, 2007

The Alberta advantage, continued

The disparities in Canada between an economically dynamic and demographically relatively buoyant province of Alberta and the rest of the country that I wrote about last year have, if anything, only grown. A recent recent report by the Centre for the Study of Living Standards has suggested that strong economic growth in the western provinces of British Columbia and Alberta has driven high levels of internal migration, the result reallocation of Canada's labour force resulting in net benefit for the country as a whole but net losses for the other eight of Canada's ten provinces.

The study estimated that interprovincial migration boosted the overall output of the Canadian economy by about $2-billion last year as unemployed people who moved found jobs, and as employed workers moved to provinces and jobs with higher productivity levels. And it accounted for nearly six per cent of economic growth last year, up 2.6% over the 1987-2006 period.

While the migration of workers has surged in recent years, the study found there were gains in both net economic output and productivity due to interprovincial migration in all years in the 1987-2006 period. Last year, higher output per worker accounted for about two-thirds of the gains, while the increase in employment in provinces that gained workers accounted for the rest, the study said.

"Despite large net gains at the national level, only two provinces actually had net gains whereas eight had net losses," it said, estimating the increase in economic output for Alberta at a significant $4.6-billion, and for British Columbia at a modest $238.4-million.

[. . .]

When the average worker moves from a less productive to a more productive region, the worker's productivity rises and the difference can be attributed to migration. When persons not employed in one province move to take a job in another all their output can be attributed to migration, it says.

Interprovincial migrants also were much more likely to be in the 15-44 prime working age group, tended to be more educated, and enjoyed greater increases in earnings than non-migrants.

Meanwhile, the loss in potential GDP last year in the other eight provinces, assuming all the workers who left were employed, ranged from $1.4-billion in Ontario and $487-million in Quebec, to $303-million in Manitoba and less than $200-million in each of the others.

Alberta's recent spell of strong, labour-intensive economic growth is partly associated with the exploitation of the Athabasca Tar Sands, potentially a major source of oil and other petrochemicals after processing and now economically viable in the context of high world prices for oil, but is now more broadly diversified beyond oil. This contrasts sharply with the relative weakness of other regional economies in Canada, a phenomenon with many causes. In the case of the province of Ontario, competition of between the goods of heavily industrialized province and Chinese exports is responsible for weak GDP per capita growth: "[W]hile the Ontario economy was growing at an average pace of 2.2% per year, the population was increasing by 1.2%, meaning that real GDP per capita (standard of living) was growing about 1.0% per year on average. This was well short of the 1.7% Canadian average, let alone the 3.0% per year pace for Alberta." Ontario's weakness and the relative decline of British Columbia over the 1990s leaves Canada, in one observer's words, with only "one and a half" "have" provinces.

The ironic thing? Even with the ongoing population shift, Alberta is still experiencing labour shortages which might very well stall economic growth, as Nicholas Köhler explained earlier this month in the newsmagazine MacLean's.

Alberta is wracked by a labour shortage, its jobless rate hitting a historic low of 3.4 per cent last year. The Conference Board of Canada predicts that, by 2025, Alberta will be short as many as 330,000 workers; other forecasts are more dire, envisioning a demand for 400,000 more labourers by 2015. (So frustrated are some by a lack of bodies that, in an interview with Maclean's, one observer charged Dave Bronconnier, the mayor of Calgary, with throwing too much manpower at the city's current infrastructure works.) Above those local considerations, prices for raw materials jumped worldwide. Driven largely by insatiable China, steel prices, for example, rose by 70 per cent in the past five years.

The result has been oil sands overruns -- and even the occasional surrender to circumstance. Capital costs have tripled in a decade, and doubled in the last three years. Last summer, Shell Canada Ltd., now wholly owned by Royal Dutch Shell PLC, said costs for expanding the Athabasca Oil Sands Project would rise as much as 75 per cent from earlier estimates, to $12.8 billion. Next, Nexen Inc. said costs at the Long Lake project would drive estimates up 20 per cent, to $4.6 billion. Canadian Natural Resources Ltd. said in March it wouldn't move on plans to build a bitumen processing plant, or upgrader. Synenco Energy Inc., meanwhile, shelved its upgrader in May. "I don't think it's an anomaly," says Mark Friesen, a Calgary-based analyst at FirstEnergy Capital Corp. who subtitled a recent report on Synenco "A Warning Shot Across the Bow for Oil Sands Economics." "I think it's an indication of how difficult the environment is. If we're not careful, more projects may end up being delayed or cancelled."

The study estimated that interprovincial migration boosted the overall output of the Canadian economy by about $2-billion last year as unemployed people who moved found jobs, and as employed workers moved to provinces and jobs with higher productivity levels. And it accounted for nearly six per cent of economic growth last year, up 2.6% over the 1987-2006 period.

While the migration of workers has surged in recent years, the study found there were gains in both net economic output and productivity due to interprovincial migration in all years in the 1987-2006 period. Last year, higher output per worker accounted for about two-thirds of the gains, while the increase in employment in provinces that gained workers accounted for the rest, the study said.

"Despite large net gains at the national level, only two provinces actually had net gains whereas eight had net losses," it said, estimating the increase in economic output for Alberta at a significant $4.6-billion, and for British Columbia at a modest $238.4-million.

[. . .]

When the average worker moves from a less productive to a more productive region, the worker's productivity rises and the difference can be attributed to migration. When persons not employed in one province move to take a job in another all their output can be attributed to migration, it says.

Interprovincial migrants also were much more likely to be in the 15-44 prime working age group, tended to be more educated, and enjoyed greater increases in earnings than non-migrants.

Meanwhile, the loss in potential GDP last year in the other eight provinces, assuming all the workers who left were employed, ranged from $1.4-billion in Ontario and $487-million in Quebec, to $303-million in Manitoba and less than $200-million in each of the others.

Alberta's recent spell of strong, labour-intensive economic growth is partly associated with the exploitation of the Athabasca Tar Sands, potentially a major source of oil and other petrochemicals after processing and now economically viable in the context of high world prices for oil, but is now more broadly diversified beyond oil. This contrasts sharply with the relative weakness of other regional economies in Canada, a phenomenon with many causes. In the case of the province of Ontario, competition of between the goods of heavily industrialized province and Chinese exports is responsible for weak GDP per capita growth: "[W]hile the Ontario economy was growing at an average pace of 2.2% per year, the population was increasing by 1.2%, meaning that real GDP per capita (standard of living) was growing about 1.0% per year on average. This was well short of the 1.7% Canadian average, let alone the 3.0% per year pace for Alberta." Ontario's weakness and the relative decline of British Columbia over the 1990s leaves Canada, in one observer's words, with only "one and a half" "have" provinces.

The ironic thing? Even with the ongoing population shift, Alberta is still experiencing labour shortages which might very well stall economic growth, as Nicholas Köhler explained earlier this month in the newsmagazine MacLean's.

Alberta is wracked by a labour shortage, its jobless rate hitting a historic low of 3.4 per cent last year. The Conference Board of Canada predicts that, by 2025, Alberta will be short as many as 330,000 workers; other forecasts are more dire, envisioning a demand for 400,000 more labourers by 2015. (So frustrated are some by a lack of bodies that, in an interview with Maclean's, one observer charged Dave Bronconnier, the mayor of Calgary, with throwing too much manpower at the city's current infrastructure works.) Above those local considerations, prices for raw materials jumped worldwide. Driven largely by insatiable China, steel prices, for example, rose by 70 per cent in the past five years.

The result has been oil sands overruns -- and even the occasional surrender to circumstance. Capital costs have tripled in a decade, and doubled in the last three years. Last summer, Shell Canada Ltd., now wholly owned by Royal Dutch Shell PLC, said costs for expanding the Athabasca Oil Sands Project would rise as much as 75 per cent from earlier estimates, to $12.8 billion. Next, Nexen Inc. said costs at the Long Lake project would drive estimates up 20 per cent, to $4.6 billion. Canadian Natural Resources Ltd. said in March it wouldn't move on plans to build a bitumen processing plant, or upgrader. Synenco Energy Inc., meanwhile, shelved its upgrader in May. "I don't think it's an anomaly," says Mark Friesen, a Calgary-based analyst at FirstEnergy Capital Corp. who subtitled a recent report on Synenco "A Warning Shot Across the Bow for Oil Sands Economics." "I think it's an indication of how difficult the environment is. If we're not careful, more projects may end up being delayed or cancelled."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)