Showing posts with label futurology. Show all posts

Showing posts with label futurology. Show all posts

Thursday, December 17, 2020

A brief note on the blog and on COVID-19

The subject of COVID-19, a virus that burst forth from its rom obscurity in (most likely) one population or another of wild mammals in China to become a global zoonotic pandemic, is well-suited for Demography Matters. Speaking for myself, I have felt unable to address this topic because it is so all-encompassing. It has transformed my life and those of my friends and family, it has wrought remarkable change throughhout the world, and it will inflict a shock with consequences that we are only beginning to realize.

Thirteen thousand people have died of COVID-19 in Canada as I write, and to my country's south well over 300 thousand have died in the United States, with a total of 1.6 million recorded deaths worldwide. This is not the least of it: Over at Quora, Franklin Veaux answering the question of just how a disease with a mortality rate of 1% could paralyze the United States. Even ignoring the terrible mortality that it inflicts, COVID-19 leaves many of its survivors with a host of disabilities.

Vaccines cannot come quickly enough. What will the world be like when an unprecedented global distribution of vaccines is finished, when COVID-19 becomes just another disease that we can handle? (I am struck, as a long-time student of HIV/AIDS, by the prominence of Dr. Anthony Fauci in the American and global efforts to deal with COVID-19; his new prominent appearance in the fight to deal yet another plague shows how history can rhyme strangely.) Mortality and long-term health of populations will be affected, but they will not be alone. Early signs are that the great instability and uncertainty wrought by COVID-19 has helped depressed fertility worldwide, for instance, while cross-border migration has been tamped down almost entirely. The future evolution of the world population has been marked in a way that is not going to disappear quickly.

Demography Matters will be there for it. This blog may stay on Blogger or go elsewhere (Medium looks interesting), but there remains a real need for blogs which take a look at population issues. Demography does indeed matter. Watch this space.

Labels:

covid-19,

demographics,

demography matters,

disease,

fertility,

futurology,

globalization,

health,

mortality

Wednesday, March 20, 2019

Some links: longevity, real estate, migrations, the future

I have been away on vacation in Venice--more on that later--but I am back now.

- Old age popped up as a topic in my feed. The Crux considered when human societies began to accumulate large numbers of aged people. Would there have been octogenarians in any Stone Age cultures, for instance? Information is Beautiful, meanwhile, shares an informative infographic analyzing the factors that go into extending one’s life expectancy.

- Growing populations in cities, and real estate markets hostile even to established residents, are a concern of mine in Toronto. They are shared globally: The Malta Independent examined some months ago how strong growth in the labour supply and tourism, along with capital inflows, have driven up property prices in Malta. Marginal Revolution noted there are conflicts between NIMBYism, between opposing development in established neighbourhoods, and supporting open immigration policies.

- Ethnic migrations also appeared. The Cape Breton Post shared a fascinating report about the history of the Jewish community of industrial Cape Breton, in Nova Scotia, while the Guardian of Charlottetown reports the reunification of a family of Syrian refugees on Prince Edward Island. In Eurasia, meanwhile, Window on Eurasia noted the growth of the Volga Tatar population of Moscow, something hidden by the high degree of assimilation of many of its members.

- Looking towards the future, Marginal Revolution’s Tyler Cowen was critical of the idea of limiting the number of children one has in a time of climate change. On a related theme, his co-blogger Alex Tabarrok highlights a new paper aiming to predict the future, one that argues that the greatest economic gains will eventually accrue to the densest populations. Established high-income regions, it warns, could lose out if they keep out migrants.

Labels:

ageing,

atlantic canada,

canada,

cities,

demographics,

diaspora,

economics,

future,

futurology,

history,

islands,

links,

malta,

migration,

moscow,

nova scotia,

prince edward island,

russia,

syria

Sunday, January 01, 2017

On Max Roser's A history of global living conditions in 5 charts and the future

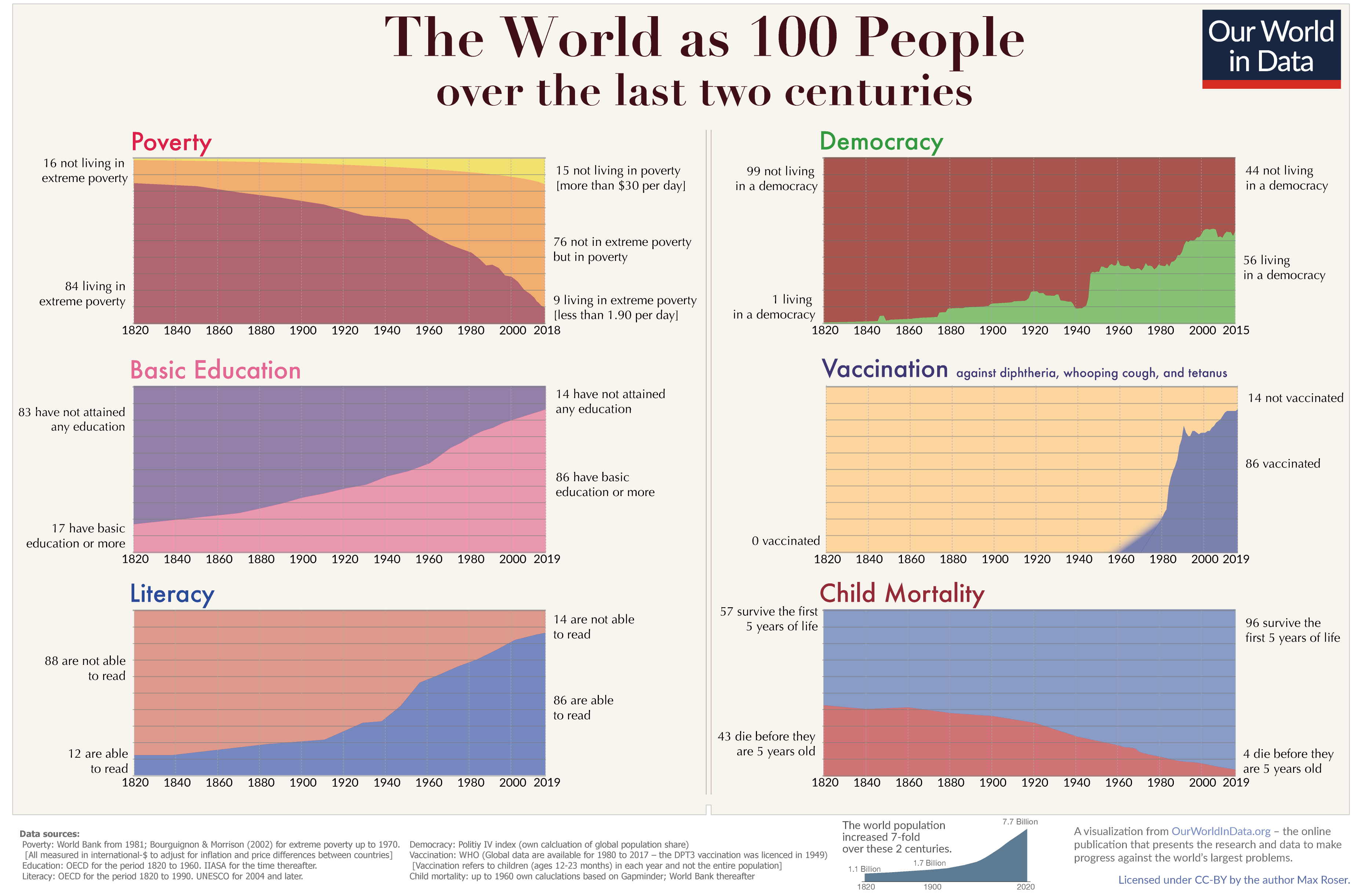

Some days ago, I saw shared on Facebook an essay, Max Roser's "A history of global living conditions in 5 charts" at the Our World in Data project. In this essay, Roser makes the argument--contrary to the zeigeist of 2016--that, in fact, in the longue durée things have been getting decidedly better for people. Extreme poverty and premature mortality have faded, rates of literacy and education have risen, and both living standards and levels of political freedom have increased hugely. (Fertility rates, Roser has noticed, have fallen markedly worldwide as a result of these trends' conjunction.) Towards the end of this, Roser created a chart exploring just how radically things have changed.

The shift has been marked. Back in December 2010, I wrote about the demographic dynamics of the Roman Empire and other pre-modern polities, noting after Vaclav Smil that there are no modern equivalents to the terrible suffering of the past anywhere on our world now. Even central Africa, probably the least developed area of the world, is better off. More, as Roser notes, the dynamics to date are positive: rates of premature mortality and undereducation are falling, for instance.

Why is there unfounded pessimism about the world's future prospects? Roser suggests that the answer can be found in our failure to adequately understand the significance of long-running trends.

One reason why the media focusses on things that go wrong is that the media focusses on single events and single events are often bad – look at the news: plane crashes, terrorism attacks, natural disasters, election outcomes that we are not happy with. Positive developments on the other hand often happen very slowly and never make the headlines in the event-obsessed media.

The result of a media – and education system – that fails to present quantitative information on long-run developments is that the huge majority of people is completely ignorant about global development. Even the decline of global extreme poverty – by any standard one of the most important developments in our lifetime – is only known by a small fraction of the population of the UK (10%) or the US (5%). In both country’s the majority of people think that the share living in extreme poverty has increased. Two thirds in the US even think the share in extreme poverty has ‘almost doubled’. When we are ignorant about global development it is not surprising that few think that the world is getting better.

The only way to tell a history of everyone is to use statistics, only then can we hope to get an overview over the lives of the 22 billion people that lived in the last 200 years. The developments that these statistics reveal transform our global living conditions – slowly but steadily. They are reported in this online publication – Our World in Data – that my team and I have been building over the last years. We see it as a resource to show these long-term developments and thereby complement the information in the news that focus on events.

The difficulty for telling the history of how everyone’s lives changed over the last 200 years is that you cannot pick single stories. Stories about individual people are much more engaging – our minds like these stories – but they cannot be representative for how the world has changed. To achieve a representation of how the world has changed at large you have to tell many, many stories all at once; and that is statistics.

Individual stories matter, but statistical trends like these also merited tracking. Let's try to do them both this coming year, here at Demography Matters and elsewhere.

Labels:

demographics,

futurology,

globalization,

statistics

Saturday, October 22, 2016

On the idea that the human life expectancy is limited to 115 years

The theme of longevity is one that Demography Matters has touched upon in the past. I've written about two interesting case studies, in February 2010 about the Abkhaz of the Caucasus and their mythic longevity, and then in June 2014 about the factors behind the extended life expectancy of the inhabitants of the Greek Aegean island of Icaria. I've also written about broader trends, in December 2014 noting the remarkable global trends which have seen global life expectancy rise substantially. The news, announced earlier this month, that built-in biological failings might limit the human life expectancy to 115 years or so, definitely caught my attention. The study--available here--was outlined by Linda Geddes at Nature.

To investigate, Jan Vijg, a geneticist at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City and his colleagues turned to the Human Mortality Database, which spans 38 countries and is jointly run by US and German demographers. They reasoned that if there’s no upper limit on lifespan, then the biggest increase in survival should be experienced by ever-older age groups as the years pass and medicine improves. Instead, they found that the age with the greatest improvement in survival got steadily higher since the early twentieth century, but then started to plateau at about 99 in 1980. (The age has since increased by a very small amount).

The researchers went on to look at the International Database on Longevity, which focuses on the oldest people and is run by an international team. They found that the maximum reported age of death — the age of the oldest person to die in a given year — in France, Japan, the United States and the United Kingdom (the countries with the largest numbers of supercentenarians) increased rapidly between the 1970s and early 1990s but plateaued in the mid-1990s at 114.9 years. The researchers observed the same trend when they considered the second, third, fourth and fifth oldest person who died in a given year — and a similar peak age of 115 years old when they tracked the maximum annual age of death using another database run by the international Gerontology Research Group, which validates supercentenarian claims.

Vijg’s team concludes that there is a natural limit to human lifespan of about 115 years old. There will still be occasional outliers like Calment, but he calculates that the probability of a person exceeding 125 in any given year is less than 1 in 10,000.

The limit is surprising, says Vijg, given that the world’s population is increasing — supplying an ever-increasing pool of people who could live longer — and that nutrition and general health have improved. “If anything you would have expected more Jeanne Calments in recent years, but there aren’t."

But not everyone agrees with his team's interpretation. The age experiencing the greatest increase in survival may have plateaued in many countries, says James Vaupel, founding director of the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Rostock, Germany. But it has not yet plateaued in some that are particularly relevant to this research, namely Japan, which has the world’s highest life expectancy — 83.7 years for those born in 2015, nor in France or Italy, which have large populations and high life expectancies.

Vijg’s paper includes “one-sided conclusions”, says Vaupel. But Vijg argues that the increase in the survival age in even these three countries has significantly slowed down in recent years and so seems to be trending towards no increase.

This report garnered a lot of attention from the mainstream media, The Guardian, NPR, and The Atlantic providing some insightful commentary. The Atlantic notes the arguments that frailties inherent in the human organism make it unlikely that this ceiling will be raised, not without unforeseen technological advances.

The ceiling is probably hardwired into our biology. As we grow older, we slowly accumulate damage to our DNA and other molecules, which turns the intricate machinery of our cells into a creaky, dysfunctional mess. In most cases, that decline leads to diseases of old age, like cancer, heart disease, or Alzheimer’s. But if people live past their 80s or 90s, their odds of getting such illnesses actually start to fall—perhaps because they have protective genes. Supercentenarians don’t tend to die of major diseases—Jeanne Calment died of natural causes—and many of them are physically independent even at the end of their lives. But they still die, “simply because too many of their bodily functions fail,” says Vijg. “They can no longer continue to live.”

[. . . I]f early development and childhood experiences are so important to our future health, it’s notable that today’s centenarians were born in the 1900s. It might be that longevity records “haven’t yet seen the impact of the improved sanitation, healthcare, vaccinations, and hygiene advances that took place in the 1930s and later,” says Holly Brown-Borg from the University of North Dakota. Or perhaps, “our poor diets and lack of exercise have countered those gains.”

That’s unlikely to matter much, says Vijg. “Once you survive your childhood, you’re really more likely to survive over long periods of time. And there have been enormous advances in keeping older people alive much longer. We’ve continued to make progress in medical care and safety standards, and there are more and more people. You can’t explain the fact that there aren’t older people that Jeanne Clement except to say that we’ve hit a ceiling.”

We have pushed that ceiling upward for laboratory animals, like worms, flies, and rodents. But these creatures were specifically bred by scientists to grow fast and reproduce rapidly. Many of the techniques for extending their lives, from drugs to calorie restriction, probably work by simply slowing their artificially inflated growth.

Similar tricks might increase our healthspan, and raise our average life expectancy. But Vijg believes that the most we can hope for is to be very healthy for around 115 years, after which our bodies will just collapse.

“There’s no question that we have postponed aging,” adds Judith Campisi, from the Buck Institute for Research on Aging. “But to engineer an increase in maximum lifespan, we’ll probably have to modify so many genes that it won’t be possible within our lifespan—or even our grandchildren’s lifespan.”

Even granting the arguments of Campisi and others that--assuming this limit does exist--this limit of 115 years cannot be breached in the foreseeable future, there's still much that can be done. Most obviously, in no country does the average life expectancy actually reach 115 years, or come close to it. Moreover, as noted by many of the people interviewed, there is still much that can be conceivably done to make the human process easier. Biomedical interventions into the aging process and specific diseases aside, I noted in my treatments of the Abkhaz and the Icarians specific things that can be done--inclusive social structures, for instance, and relatively healthy diets--that can do much to extend not only longevity but healthy lifespans. The commentary at Forbes, concentrating on the specific case of Japan, provides stil another example. In a generation's time--perhaps even in my generation--decline and death may end up being postponed and not so nearly drawn out.

The consequences of any scenario involving extended longevity are notably significant. A worst-case scenario might involve an extension of human life expectancy towards supercentenarian territory without a corresponding increase in a person's active and healthy lifespans. The financial costs of supporting these people for additional decades would be extreme, to say nothing of the human cost to specific individuals who might well not relish added years of suffering. The Greek mythological figure of Tithonus, who suffered the tragic consequences of being granted immortality but not eternal youth, comes to mind. Conversely, a scenario where longevity and health are extended could have very positive consequences.

Sunday, February 28, 2016

On the demographic limits to future economic growth

On Thursday the 21st in The Globe and Mail, journalist Konrad Yakabuski had an article published, "Fewer economic miracles in a world with fewer demographic explosions". Drawing particularly on Ruchir Sharma's March/April 2016 Foreign Affairs article "The Demographics of Stagnation".

Ruchir Sharma, the head of emerging markets and global macro at Morgan Stanley Investment Management, warns that policy-makers have been looking in all the wrong places to explain what has become the weakest global economic recovery in postwar history. The causes aren’t high public and private indebtedness, income inequality or overcautious investors, although those factors don’t help. The real problem is a dramatic slowdown in labour market growth rates around the world.

It seems counterintuitive to be worrying about labour market shortages when automation is rendering more and more jobs redundant and unemployment remains at near-record levels in most of Europe. Even the U.S. unemployment rate, which is at an eight-year low of 4.9 per cent, cannot mask the fact that the participation rate (the percentage of working-age Americans in the labour force) is at a four-decade low, leaving millions of potential workers idling on the sidelines.

But by exhaustively tracking population and gross domestic product growth over one-decade periods since 1960, Mr. Sharma comes to a several sobering conclusions. One is that “explosions in the number of workers deserve a great deal of credit for economic miracles.” Another, he writes in an article published this week in Foreign Affairs, is that “a world with fewer fast-growing working-age populations will experience fewer economic miracles.”

Between 1960 and 2005, the expansion of the labour force and rising productivity determined growth rates almost everywhere. During that 45-year period, the global labour force grew at an average annual rate of 1.8 per cent. Since 2005, the rate has slipped to 1.1 per cent and is expected to fall further in all but a few outlying nations (such as Nigeria) as the consequences of a decades-long decline in fertility rates leave even emerging economies facing dwindling influxes of new workers.

[. . .]

“Over the next five years, the working-age population growth rate will likely dip below the 2-per-cent threshold in all the major emerging economies,” Mr. Sharma says. “In Brazil, India, Indonesia and Mexico, it is expected to fall to 1.5 per cent or less. And in China, Poland, Russia and Thailand, the working-age population is expected to shrink.” The most worrying slowdown is China’s, with “dire” implications for the rest of the world. In the past five years, Mr. Sharma notes, China alone accounted for a third of global growth.

This is the sort of scenario that long-time readers of Demography Matters have been forewarned about for some time, thanks to the insights of dear comrade Edward Hugh. The 21st century will be a world, it seems, where human capital, in relative abundance or otherwise, will play a critical role in determining the futures of world economies. Individuals, groups, entire communities or countries relatively well-positioned might well be strong. I suspect that in the coming decades, people with the right skills will prosper. Other regions, though? I can easily see any number of major economies not adapting well. Can Germany, locomotive of the Eurozone, really outlast sustained low fertility? What of China? What of ... ? One can only hope that the robots will come on stream at the right time.

Labels:

demographics,

economics,

futurology,

globalization

Monday, January 18, 2016

Changing world population balances, 1800 to 2100

The Russian Demographics Blog was the most recent source to link to Max Galka's remarkable map showing changing populations in the recent past and the projected future.

For thousands of years, Asia has been the population center of the world. But that’s about to change.

Asia contains 7 of the 10 most populous countries in the world, the two largest of which, China and India, each individually have larger populations than Africa, Europe, or the Americas. And as I’ve demonstrated previously, the eye-popping population density in regions such as Tokyo and Bangladesh is an order of magnitude greater than anywhere in the western world.

Two hundred years ago, the figures were even more extreme. In 1800, nearly two thirds of the world lived in Asia. And at that time China had a larger population than Africa, Europe, and the Americas combined.

Asia dominates the world population landscape, and it has for at least the last two and a half thousand years. [. . . T]he relative population sizes of Asia, Africa, and Europe have remained surprisingly constant for thousands of years. Since at least 400 BC, 60% or more of the world has lived in Asia.

According to the U.N. Population Division, the population of Africa is poised to explode during the next 85 years, quadrupling in size by 2100.

The U.N. attributes this change to two factors: Africa’s high fertility rates (African women have on average 4.7 children vs. a global average of 2.5) and its young population, many of whom will be reaching adulthood in the coming years and having children of their own.

Wednesday, November 04, 2015

On a relationship between climate change in the United States and falling birth rates

On my RSS feed, I recently came across a paper looking at the relationship between climate change and (American) demographics. NBER Working Paper No. 21681, "Maybe Next Month? Temperature Shocks, Climate Change, and Dynamic Adjustments in Birth Rates", written by Alan Barreca, Olivier Deschenes, and Melanie Guldi, makes some noteworthy claims. The paper is behind a paywall, but the abstract is at least indicative.

Dynamic adjustments could be a useful strategy for mitigating the costs of acute environmental shocks when timing is not a strictly binding constraint. To investigate whether such adjustments could apply to fertility, we estimate the effects of temperature shocks on birth rates in the United States between 1931 and 2010. Our innovative approach allows for presumably random variation in the distribution of daily temperatures to affect birth rates up to 24 months into the future. We find that additional days above 80 °F cause a large decline in birth rates approximately 8 to 10 months later. The initial decline is followed by a partial rebound in births over the next few months implying that populations can mitigate the fertility cost of temperature shocks by shifting conception month. This dynamic adjustment helps explain the observed decline in birth rates during the spring and subsequent increase during the summer. The lack of a full rebound suggests that increased temperatures due to climate change may reduce population growth rates in the coming century. As an added cost, climate change will shift even more births to the summer months when third trimester exposure to dangerously high temperatures increases. Based on our analysis of historical changes in the temperature-fertility relationship, we conclude air conditioning could be used to substantially offset the fertility costs of climate change.

My source, the Bloomberg article "Climate Change Kills the Mood: Economists Warn of Less Sex on a Warmer Planet" written by Eric Roston, goes into somewhat more detail about the claims made.

An extra "hot day" (the economists use quotation marks with the phrase) leads to a 0.4 percent drop in birth rates nine months later, or 1,165 fewer deliveries across the U.S. A rebound in subsequent months makes up just 32 percent of the gap.

[. . .]

The researchers assume that climate change will proceed according to the most severe scenarios, with no substantial efforts to reduce emissions. The scenario they use projects that from 2070 to 2099, the U.S. may have 64 more days above 80F than in the baseline period from 1990 to 2002, which had 31. The result? The U.S. may see a 2.6 percent decline in its birth rate, or 107,000 fewer deliveries a year.

If this is correct, it's tempting to wonder about the extent this would be replicated in other areas of the world. What about other warming areas? Does cooling have a relationship to fertility?

Labels:

demographics,

environment,

futurology,

united states

Saturday, October 31, 2015

What do you think are some overlooked demographic issues?

I would like to assure everyone that I am working on a post in response to yesterday's news that China is shifting to a two-child policy. (Brief reaction: I do not think it will change much, given the consistently low level of fertility in East Asia and Chinese-majority societies. Demographic changes in China will come in other ways.)

In the meantime, I am curious to know what readers might think are demographic issues of note that are not being covered, here, in the larger blogosphere, and in the mass media and academic journals. What's being overlooked?

Thursday, February 12, 2015

"Depopulation: An Investor's Guide to Value in the Twenty-First Century"

Earlier this month, Marginal Revolution's Tyler Cowen linked to an interesting-sounding new e-book available on the Amazon Kindle platform, Depopulation: An Investor's Guide to Value in the Twenty-First Century by Philip Auerswald and Joon Yun.

Depopulation is a solid, inexpensive, and fairly quick read. Just 70 pages in length, Auerswald and Yun's e-book does what it promises in providing its readers with a quick look at some of the likely economic consequences of eventual global population decline. What asset classes will be hardest hit? Will it even make sense to own assets for investment purposes? How is migration, both intra-national and international, likely to change things? What sorts of policies might be adopted to ameliorate the effects of this change? What other unexpected consequences might come of all this? That the authors can't provide firm answers is owing to the relative novelty of the situation facing an increasingly large majority of the world population.

My substantial disagreement with the authors relates to the idea of competition over resources. Even in a hypothetical world of falling global populations, resource scarcity could still easily be an issue. I could imagine a future world less populous than ours but one with more competition over a resource, whether because potential consumers are wealthier and better able to make claims upon a resource (real estate, say, or some natural resource) or because the natural resources available are falling more quickly than the relevant population. This disagreement is more a matter of emphasis on my part than a substantial objection, mind.

I liked Depopulation, as a thought-provoking guide to our changing world's future. I think that you would, too.

Labels:

demographics,

economics,

futurology,

links,

popular culture

Friday, January 16, 2015

"Humanity’s Future: Below Replacement Fertility?"

Reading my Inter Press Service RSS feed this evening, I came across Joseph Chamie's essay arguing that, on current trends, the entire world may shift to below-replacement fertility in a surprisingly short time. At the end of his analysis, he concludes that this trend is likely to spread worldwide.

According to United Nations medium-variant population projections, by mid-century the number of countries with below replacement fertility is expected to nearly double, reaching 139 countries. Together those countries will account for 75 percent of the world’s population at that time.

Some of the populous countries expected to fall below the replacement fertility level by 2050 include Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Mexico, South Africa and Turkey. Looking further into the future, below replacement fertility is expected in 184 countries by the end of the century, with the global fertility rate falling below two births per woman.

It is certainly difficult to imagine rapid transitions to low fertility in today’s high-fertility countries, such as Chad, Mali, Niger and Nigeria, where average rates are more than six births per woman. However, rapid transitions from high to low fertility levels have happened in diverse social, economic and political settings.

With social and economic development, including those forces favouring low fertility, and the changing lifestyles of women and men, the transition to below replacement fertility in nearly all the remaining countries with high birth rates may well occur in the coming decades of the 21st century.

A question to our readers: Do you think this is plausible? What do you think this world would look like?

Thursday, January 01, 2015

Yekaterina Schulmann on the problems of pop futurologists in Russia (and elsewhere)

Paul Goble of Window on Eurasia, a noteworthy blog touching on Eurasian affairs, recently linked to and summarized an essay by Yekaterina Schulmann in Russia's Vedomosti about the problems with many of the predictions made by Russians predicting the future.

I found this article vert broadly relevant. The twelve kinds of errors identified by Schulman, rooted in deep misunderstandings of the way societies and their institutions actually work, actually are quite relevant in avoiding the creation of all kinds of ill-founded scenarios, and in creating the sorts of scenarios which actually are plausible. Yes, this works in scenarios of demographic scenarios as well. I would hope that I myself, and my fellow bloggers here, have avoided making the sorts of errors Schulmann identified, and at the very least we've been careful to explain why certain parallels and arguments make sense.

Below, I quote from the first five summaries included Goble's neat summary of Schulmann's article.

Personification. There is a widespread tendency to elevate the role of personality in history, with statements of the kind “if there wasn’t Citizen X, there wouldn’t be a Russia.” But that is nonsense: “a personality can disappear, and a regime survive – or the opposite can happen.”

Historical Parallels. Pace Marx, Schulmann says, “history does not repeat itself either as a tragedy or as a farce.” The reason is simple: there is such a large number of historical facts that each event is a product of a different combination than its predecessor. There may be similarities but there are no identities, whatever commentators say.

Geographic Cretinism. Geographic determinism follows from the previous point, with this difference: for those who promote this idea, “geography is fate” and time and all other factors are irrelevant. Such people can’t explain why some regimes a world away from each other are the same or why some regimes so close together – like the two Koreas – are so different.

Vulgar Materialism. A subspecies of geographic determinism is resource determinism, a view that holds that the economic resources of a state define all its possibilities, a view that ignores that different countries with similar resources behave in completely different ways.

Vulgar Idealism. Those who fall into this trap, into the belief that ideas once announced eventually take physical shape forget that the authorities “exist not in a Platonic universe” where ideas are the only factors but in one where all kinds of things affect decisions and outcomes.

Read the rest, at Window on Eurasia and at Vedomosti, enjoy, and think.

Happy New Year!

Tuesday, December 23, 2014

Notes on the demographic future of Cuba

In the past, Demography Matters has examined the demographic issues of Cuba at some length. In a August 2006, I noted that all of the predictions for Cuba expected rapid aging of the population, as a consequence of low fertility and sustained emigration, leading to substantial shrinkage of the country's workforce. In a July 2009 post, I noted that the Cuban population had already begun to shrink, and in a May 2010 post I argued that Cuba was missing too many opportunities for change, too many windows closing while it still had a relatively young population. The post-Communist example of Bulgaria was something I raised in 2006, with its spectre of incipient depopulation and the pre-existing example of massive Cuban emigration to the United States. Nothing that has happened since has convinced me this is not a plausible future for Cuba.

And now? Some of the announced changes by the United States, particularly the expanded volume of remittances that can be sent to Cuba by migrants and increased ease of movement and communication across the Florida Straits, might make provide greater incentives for migration. As a November 2014 Havana Times article noted, in the two decades after the Cold War a half-million Cubans emigrated to the United States. Why not more, if nothing else changes in Cuba?

I suspect that Cuba might not be coming to the last of its opportunities to get rich before it grows old. Will Cuba manage this transition in a new era of improved Cuban-American relations? One can only hope.

UPDATE: Marginal Revolution's Tyler Cowen argues that there are good reasons, including a vulnerable export sector, institutional weaknesses, and brain drain, to be skeptical of post-Communist Cuba's economic chances. (He also lists some reasons for hope, including high levels of human development, abundant natural resources, and a talented diaspora in the United States.)

Labels:

caribbean,

cuba,

demographics,

fertility,

futurology,

migration

Tuesday, December 16, 2014

On how Afghanistan shows the importance of having a census

A recent article by Joseph Goldstein in The New York Times, "For Afghans, Name and Birthdate Census Questions Are Not So Simple", caught my attention.

Wikipedia's "Demographics of Afghanistan" article notes that, apart from a survey performed in 2009, Afghanistan really has no firm data on demographic trends at all. This, as Goldstein notes, can harm individual lives.

After long delays, false starts and squandered millions in foreign aid, the great Afghan census is finally underway. The process is more than an exercise in counting bodies but one that, officials hope, will head off the kind of voter fraud that plagued the presidential election this past year.

The census teams generally include a man and a woman who often spend considerable time waiting in front of doors that never open, often because of purdah, the custom of sequestering women indoors away from men not their husbands or relatives and requiring a burqa when outside.

[. . .]

Since census workers began knocking on doors in Kabul this year, they have registered 70,000 people — just 2 percent of the city. Optimistic Afghan officials say it will take years before the entire country is surveyed.

“We believe we will reach 70 percent of the population in five years,” said Homayoun Mohtaat, the project’s director.

Nobody knows just how many people reside in Afghanistan. The last census, in 1979, found some 14.6 million people. Afghanistan’s Population Registration Department currently has records for about 17 million Afghan citizens, according to officials.

Each name is listed in a clothbound ledger book stacked on sagging metal racks in four dusty rooms in the offices of the department, a government agency.

For years, this is where citizens have come to seek a passport, join the army or change their marital status. Before that can happen, though, the petitioner’s identity must be verified in one of the books. Clerks say they almost never fail to locate an entry, except for people with the bad luck of being listed on the first or last page. Those names and photos have largely worn away from use over the decades.

The clerks who work here have the carnival-worthy ability to guess a person’s age within a year, a necessity in a place where few actually know how old they are.

Mr. Mohtaat guesses the census will yield a count of 35 million to 40 million Afghans.

As Sune Engel Rasmussen writing in The Guardian noted in the case of Kabul, the lack of firm data makes it difficult for governments and others to get a handle on the country's problems. The case of booming Kabul is the particular focus of Rasmussen's article, but doubtless similar stories could be told about other Afghan cities and regions.

Though exact data is impossible to obtain (the last official census was conducted in 1979), Kabul is estimated to be the fifth fastest growing city in the world, with a population which has ballooned from approximately 1.5 million in 2001 to around 6 million people now. The rapid urbanisation is taking a heavy toll on a city originally designed for around 700,000 people. An estimated 70% of Kabul’s residents live in informal or illegal settlements.Afghanistan has many problems. One particularly important problem, I'd argue, is the lack of firm data about just who is living in Afghanistan and what they're doing. Without good data, many things become difficult. Here's to hoping that Afghanistan succeeds in this particular project.

“The situation is putting a strain on the existing infrastructure and resources – and makes it difficult to ensure security across Kabul,” said Prasant Naik, country director of the Norwegian Refugee Council, which provides legal counselling and shelter to displaced Afghans and is one of the largest humanitarian organisations in Afghanistan.

A significant share of Kabul’s economy is driven by illicit businesses, such as the drug trade, facilitated by corruption. (According to a recent survey by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, Afghanistan’s opium cultivation hit record levels this year.)

With economic growth slowed from 9% in 2003 to 3.2% in 2014, jobs are scarce and the vast majority of Kabul’s workers are either self-employed or casual labourers.

Labels:

afghanistan,

census,

central asia,

demographics,

futurology,

middle east,

statistics

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)