Friday, April 28, 2006

Scrutinizing low fertility

Lets begin with some empirical evidence though to frame the theme. A research paper from February this year has all the relevant data which points to the low fertility in Europe and the rest of the world. Hans-Peter Kohler, Francesco, C. Billari José, and José Antonio Ortega entitled "Low Fertility in Europe: Causes, Implications and Policy Options"; (from School of Arts and Science - Pennsylvania Univerisity).

The global population is at a turning point. At the end of 2004, the majority of the world’s population is believed to live in countries or regions below-replacement fertility, and the earlier distinct fertility regimes, ‘developed’ and ‘developing’, are increasingly disappearing in global comparisons of fertility levels (Wilson 2001, 2004). Several aspects of this convergence towards low fertility are particularly striking. First, the spread of below-replacement fertility to formerly high fertility countries has occurred at a remarkably rapid

pace and implied a global convergence of fertility indicators that has been quicker than the convergence of many other socioeconomic characteristics. Second, earlier notions that fertility levels may naturally stabilize close to replacement level—that is fertility levels with slightly more than two children per women—have been shattered.

(...)

It is clear that current social and economic institutions are not sustainable in light of these trends, and individual’s life-courses already have been—and will continue to be—transformed in response to reductions in fertility and increases in longevity. Adjusting to the demographic reality of the 21st century will therefore constitute a major challenge for policy makers and companies on the one, and for individuals and families on the other side."

For a more boiled down version see the article from the Economist's European columnist Charlemagne - The fertility bust. (walled for non-subcribers!)

The interesting thing for me in this case is not so much the political and economic implication of sustained low fertility although this is clearly very important and interesting, but why we are seing this low fertility? The argument which is mostly invoked in mainstream discourses is that women's entrance into the workforce has wielded a pressure by the family as an institution pushing birth rates down; i.e. the labour force participation argument. The paper mentioned above obviously engages in a thorough discussion of the reasons for the sustainable low-replacement fertility but for example in a European context differences in fertility still has experts (in this case the the Paris-based National Institute of Demographic Studies (INED)) wondering.

Tuesday, April 25, 2006

And in Italy ...

Concerns over Italy's ageing population were fuelled on Monday by the release of a report showing that the country's grey army has swelled to some 11.5 million, or almost 20% of the population.

The report by national statistics bureau Istat said that a record 19.5% of Italians are now 65 or over, making Italy one of the world's 'greyest' societies.

It warned that unless the trend changed, the figure was likely to hit 34% by 2050.

Under-18s account for just 17.1% of the population compared to 18.4% in 1995, Istat said, projecting a fall to 15.4% by 2050 if current trends continue.

It stressed that Italy, which has a population of 58 million, could soon find itself with one in every four people over 65 and only one in every eight under 18.

On a brighter note, Istat highlighted a surge in the birth rate after years of decline.

It said the average number of births per female was now 1.34, well below the replacement level of 2.2 for a stable population but nonetheless the highest rate in Italy in 15 years.

In 1995, the country's fertility rate sank to a record low of 1.19. At one time, Italy had the highest birth rate in Western Europe and in 1970, Italian women had an average 2.5 children each. Istat noted that births were picking up in northern and central Italy in particular. In the north, the fertility rate rose from 1.05 in 1995 to 1.34 in 2005 and in central regions from 1.07 to 1.29.

In the south of Italy, the fertility rate fell from 1.41 to 1.35 over the same period and the regions that currently show the lowest rates of all are Sardinia (1.07), and Molise and Basilicata (1.14).

The report also revealed that the region with the highest life expectancy rate was Marche in the central Adriatic area, where women can expect to live until 84.7 and men until 78.8.

Campania around Naples in the south was the region with the lowest life expectancy rate, put at 81.8 for women and 76.1 for men.

The convergence of the three regions of Italy--North, Center, and South--towards similar fertility rates is perhaps the most noteworthy new fact reported here. The Italian South once was notable for its relatively higher fertility rates, not only in an Italian context but in a world context. No longer.

Ericsson Offers Redundancy To Workers In The 35 to 50 Age Group

Well, I think this certainly is news. And it fits in with the findings of ongoing research from Italian economist Francesco Daveri. See especially working paper 309: "Age, technology and labour costs", which examines the case of Finland and especially Nokia (available on this page, abstract pasted at the bottom of this post).

Ericsson, the telecoms equipment maker, on Monday offered a voluntary redundancy package to up to 1,000 of its Sweden-based employees between the ages of 35 and 50. The unprecedented move is designed to make way for younger workers.

The world's biggest supplier of mobile phone networks, which more than halved its headcount during a dramatic restructuring programme in 2000-02, said the measure was necessary to ensure the competitiveness of the company in the next decade.

"The purpose of this programme is to correct an age structure that is unbalanced," said Marita Hellberg, global head of human resources, told the Financial Times. "We would like to make sure we employ more young people in order not to miss a generation in 10 years' time," Ms Hellberg said.

According to Ms Hellberg, Ericsson's age structure had become too heavily biased to the 35-50 age group in the aftermath of its restructuring programme.

Employees aged between 35 and 50 with a minimum of six years' service are eligible for the voluntary redundancy package that comprises 12-18 months' salary, a SKr50,000 ($6,600) pay-out and the chance to participate in a career change programme.

Now here's the abstract of the Francesco Daveri and Mika Maliranta, Age, Technology and Labour Costs research:

Is the process of workforce aging a burden or a blessing for the firm? Our paper seeks to answer this question by providing evidence on the age-productivity and age-earnings profiles for a sample of plants in three manufacturing industries (“forest”, “industrial machinery” and “electronics”) in Finland. Our main result is that exposure to rapid technological and managerial changes does make a difference for plant productivity, less so for wages. In electronics, the Finnish industry undergoing a major technological and managerial shock in the 1990s, the response of productivity to age-related variables is first sizably positive and then becomes sizably negative as one looks at plants with higher average seniority and experience. This declining part of the curve is not there either for the forest industry or for industrial machinery. It is not there either for wages in electronics. These conclusions survive when a host of other plausible productivity determinants (notably, education and plant vintage) are included in the analysis. We conclude that workforce aging may be a burden for firms in high-tech industries and less so in

other industries.

There is one logical and inescapable conclusion from all this, if "workforce aging may be a burden for firms in high-tech industries and less so in other industries" then this implies a move down, not up, the value chain for those societies with rapid ageing.

The Moldovan exodus

Why, then, has Moldova's population contracted by a quarter? Mass emigration is to blame. Soviet rule built an ambiguous Moldovan national identity, and created a relatively prosperous economy that attracted immigrants. Moldovan independence, coinciding as it did with the collapse of the Soviet economy and the civil war withy the Russophone region of Transnistria, changed this situation entirely. If Moldovans identified themselves as Romanians, Moldova could have escaped from its current situation by unifying with Romania, but the fact that three times as many people claimed to speak "Moldovan" as their first language rather than "Romanian" speaks to the strength of Moldovan national identity. Moldova is now one of the poorest countries of Europe is not the poorest, with blocked prospects for change on almost every front: talks with Transnistria keep failing, the economy remains stagnant, and public life seems to favour emigration rather than revolution.

Where do Moldovans go? Unsurprisingly, given historical links, Russia is the largest receiving country for Moldovans, although an estimated three hundred thousand Moldovans hold Romanian citizenship and appear to be echoing Romanian patterns of emigration to the southern tier of European Union states. Russia's recent retaliation against Moldovan wine exports might augur moves against Moldovan guest workers in Russia, however, possibly encouraging a new concentration on western and central Europe. If one thing is certain, it is that regardless of the direction of the emigration, it will continue. The push and pull factors that triggered this migration remain, alas.

Moldovan emigration is important on its own terms, not only for the effects of this massive emigration on Moldova but for the effect that it has on receiving countries. Moldova represents a sure pool of potential migrants for central European countries suffering population decline; already, something like one percent of the population of Romanian citizens are Moldovans. Moldova also should be studied as a prototype for rapid population decline in peripheral states; the Moldovan example has been echoed in the independent South Caucasus, arguably also in an East Germany where the population has shrunk by a quarter since reunification. Moldova's example demonstrates that, when economic conditions become sufficiently bad and/or when the benefits accuring to emigrants become sufficiently great, regional and national populations can contract at speeds more reminiscent of wartime depopulation than anything else. Where Moldova goes now, perhaps any number of relatively small and relatively impoverished states (Serbia, Paraguay, Cuba, Laos, Lesotho) in the future, perhaps--who knows?--even much larger countries.

Thursday, April 20, 2006

How Old Is Your Brain?

Really this is a very good question, and one on which more than one of the important future economic unknowns of the ageing society hinges. Is 'proportional lifecycle rescaling' a realistic hypothesis, or do our bodies in fact increasingly outlive our active brains? Well today we have news of a ludic test to examine just how fast we are, each and every one of us, cognitively ageing: a game called Brain Age, brought to us by Nintendo, just to help us exercise our minds a little (assuming, of course, that we were otherwise having difficulty in so doing):

Brain Age for the Nintendo DS is one of those titles that's not a game, but doesn't fall easily into other categories either. Based on the research of Dr. Ryuta Kawashima, it seeks to help you boost your brain power by putting you through a few simple exercises every day using reading, memory, and mathematical problems. It's an old idea, using a few minutes a day to keep the brain sharp, but you'd be surprised how good warming your brain up in the morning feels.

The wired review puts it like this:

Kawashima has a lot of tricks up his sleeve to keep you playing. Sometimes, as you turn the game on, you'll be asked to draw something (a koala bear, a fire engine) from memory. Your drawings will be saved, and if other people use the same DS cartridge, you might suffer the embarrassment of having your drawings compared to theirs.

And of course, as you continue to do the daily exercises, you'll find more and more brain-training programs. One minigame challenges you to read a literary passage out loud as fast as you can. In another, you're given a list of words and told to memorize as many as possible in two minutes, then write them down. You can play the games as much as you want during any given day, but only your first attempt each day at getting a higher "brain age" will be recorded.

As Victoria Shannon writing in the IHT wryly comments:

As the world's baby boomers advance into trifocal age, two of the most unsettling unknowns they face are whether their savings will last through retirement and whether their brains will last through their lives.

The software industry, unable to do much about the former, is turning its attention to the latter: helping to keep our brains sharp - or at least helping us think that it can - as we age.

In an age when so much attention seems to be lavished on our corporal aesthetic, it is interesting to see someone at last begining to focus on our cerebral one. I remember seeing the young Spanish bullfighter Jesulin de Ubrique respond to a TV interview question about whether he took as much trouble with what his mind looked like as he did with what his body did, with the answer 'you know, noone has ever asked me that before'(naturally he then didn't have much more to add). Maybe the days when this kind of response is possible are fast running out, and maybe slowly but steadily we are starting to see the arrival of that new range of consumer products which everyone has been forecasting will serve to characterise the arrival of what most Europeans (much to my bemusement) still tend to call 'the third age'.

Wednesday, April 19, 2006

Iceland Is Interesting

The Icelandic economy has been in the news a lot recently. I guess everyone has already read something or other about this, if not Claus has a post here (and here) which gives background and links.

Basically I had been giving the Iceland economic 'problem' a rather wide birth (until today that is), since I think it is, when all is said and done (and with full apologies in advance to all Icelanders), 'pretty small lava'. In addition since my "global imbalances" theoretical model doesn't follow the well-trodden Roubini-Setser path, and since underlying euro weakness means that the dollar can't possibly fall in any dramatic way over the longer term, and since I don't find it necessary or desireable to treat every fresh crisis as just one more example of my own pet thesis, and since anyway I have enough on my plate right now, I thought, well, let's give this party a miss. There will be plenty more later.

(For those who have missed out Brad Setser has been posting on Iceland here. Basically I have been arguing for ages with Brad that his work - which tries to address the imbalances issue without any reference to the underlying demographics - is rather like putting on a performance of Hamlet without the presence of the Prince himself. What you end up with is a good deal of interesting data, but with no theoretical model to put it all together around. And then there is the 'next crisis is around the corner-ism' of Nouriel Roubini which seems so much to drive things. My guess is that the next crisis may eventually come round the next corner, and it has a name: Iran, and what this could do to global oil prices, and what a huge spike in global oil prices could do to an already extremely weak and debt-ridden Italian economy, which is, IMHO, the weakest link in the global chain, but then, this is not an economics blog, and this is only a guess, perhaps it would be better if I try to keep to my promise to myself and stay away from all this here).

But then I open the FT today and read this:

"The Icelandic krona’s sharp fall, which put it at a 4½-year low against the euro on Tuesday, has provoked debate between political and business leaders about the country’s possible membership in the eurozone".

Iceland joining the euro, what a whacky idea was my first thought, but then 'hmmm' was my second one. Basically it is very hard to see what the logic of Iceland joining the eurozone would be, the zone itself already has got more than simply teething problems of its own to worry about, and it is hard to see how losing control of its interest rate, currency and monetary policy would help the Icelanders with the problems they have (indeed, as some have noted, it might well only add to them):

"Carsten Valgreen, chief economist at Danske Bank, said the small size of the Icelandic economy and its heavy reliance on a small number of industries left the country exposed to global market fluctuations, whether it joined the euro or not.

“The advantage would be that the credibility of monetary policy would increase,” Mr Valgreen said. “But you should also ask yourself whether a tiny economy in the middle of the Atlantic, largely based on fishing and aluminium, is really aligned with the eurozone.”"

But them, as I say, I thought hmmmm, let's take a look at the demographics here, and that's when I got that 'wow' sensation. I went to Statistics Iceland, and I read the population blurb. This is what I found:

Live births in Iceland were 4,280 in 2005. Total fertility rate was 2.1 which is higher than in most other European countries. Turkey is the only country in Europe with higher total fertility rate than Iceland. The total fertility rate has remained relatively stable in Iceland since the early 1990s. During the 20th century total fertility peaked during the 1960s to a rate of 4.3.

In recent decades Iceland has experienced pronounced increase in the age of mothers at childbirth. In the late 1970s the mean age of primparas was 21.3 as compared to 26 in 2001-2005. During this period, age-specific fertility in the age groups under 25 has declined considerably whereas fertility above the age of 30 has increased slightly.

The share of extra-marital births is higher in Iceland than in any other country of Europe and in 2005 almost two thirds of all children were born out of wedlock. The majority of these children were born to parents cohabiting and only 14.4 per cent of all mothers were not living with the child’s father. The share of extra-marital births is considerably higher in the case of first births than with children of higher parity.

Now here we can see four things.

(i) Fertility is currently near replacement level.

(ii) First birth age is high on average

(iii) Fertility first dropped and then rebounded

(iv) There is a level degree of cohabition.

Now (ii) is normally a low-fertility indicator, while (iv) is normally associated with slightly higher levels of fertility. (iii) is consistent with a slow process of birth postponement, with TFRs rebounding slightly later, as the 'missing births' appear.

So then I went and checked my lists. Iceland currently has a fertility (TFR) of 2.0, it has a life expectancy of 80.19 (which is comparatively high), and it has a median age of 34 . Now it is this latter median-age data point which produced the wow sensation, since this is very young, and puts it in the same zone as the United States, Ireland and New Zealand, ie by median age it is the archetypal country par excellance to be having the kind of credit/housing driven boom, and balance of payments deficit it has been experiencing (that is according to my 'stylised facts' version of events). This is something I hadn't picked up on before, so I took a look at the age pyramid, and sure enough it looks remarkably solid (Iceland even had minimal, but significant, inward migration last year, 3,860 in 2005).

So there we are, one problem more or less resolved. Iceland is not fundamentally unstable, and isn't about to collapse anytime soon, run on the krona or no run on the krona. Iceland probably needs to edge the retirement age upwards to compensate for the increasing life expectancy, and invest plenty in education and broadband internet connections, then they might find that being 'a tiny economy in the middle of the Atlantic' isn't really as bad as some people think it is. Of course none of this means that Iceland might not consider at some stage joining the European Union, but that, as someone once said, is another country.

Saturday, April 15, 2006

China's demographic uncertainties

Wolfgang Lutz, who runs the population-research program at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Laxenburg, Austria, is studying the range of uncertainty in China's future population trends. Lutz and his colleagues have identified at least 32 different estimates for the current fertility rate in Chinese women.

The official version is that each Chinese woman is giving birth to 1.2 children. Estimates compiled by Lutz show the actual number could be as high as 2.3 children. Such uncertainty in the Chinese data makes it difficult to say anything with confidence about the structure of the Chinese population in 2030 or 2050.

While the one-child norm is strictly enforced in urban areas with a carrot-and-stick policy, it has been less of a success in rural areas for cultural and economic reasons. In the late 1980s, the government started allowing rural couples to have a second child if their first-born was a girl.

Many girls in rural China are unregistered because their parents don't want to lose their chance to produce a male heir. The gender ratio is now close to 120 boys for 100 girls. Some of the imbalance may be real; another part may be a result of under- reporting female births.

The Lutz-coauthored paper "China’s uncertain demographic present and future" (PDF format) goes into more detail about China's future population prospects. As Wesley Ulm wrote in an essay on the topic, even before you account for the possibility that China's one-child policy is compromised by numerous exceptions based on social class, place of residence, the parents' family structures, and so on, China's population-control bureaucracy might well be hamstrung by the inability to micromanage hundreds of millions of families. Urban China may be relatively easy to control, especially given the presence there of the sort of development factors that tend to militate against high TFRs; rural China, much poorer and more neglected, is quite another.

What do Mukherjee, Lutz, and Ulm's arguments suggest? They don't contradict the very serious problems that China is going to face sooner or later. The TFR of ~1.8 children born per woman that Lutz seems to think most probable falls at the upper range of the likely TFRs raised in Claus' post, and Mukherjee and Ulm's suggestions about systematic undercounts in rural China can't be made to challenge the aging of the Chinese population. What they do suggest is that, on the basis of the statistical data most readily at hand, China might indeed be able to get rich before it grows especially old. It might not; but at this point, it's frustratingly still too early to say.

Friday, April 14, 2006

The ageing of China and a methodological approach to countries' vulnerability to ageing

"

(...)

Beginning around 2015,

Chinese leaders have to deliver economic development to create jobs for young people now, as well as prepare for elderly in the future; otherwise social unrests will certainly explode. “.....if you stop, you’re dead”, says the Chinese economist Fan Gang."

The post at the Development Bank blog has two references which are also worth mentioning:

The graying of the middle kingdom - Center for Strategic and International studies

"The age wave may pose an enormous challenge, but it need not cut short China’s astonishing rags-to-riches story—provided that China makes the right policy choices. The Graying of the Middle Kingdom argues that funded pensions are an important part of the solution. According to the report, they can help

The stakes can hardly be exaggerated. If

If

(Disclaimer; the report is from April 2004 so you might know about this)

The 2003 ageing vulnerability index - Center for Strategic and International Studies

This one takes a little more scrutiny and care in my opinion. Basically, the paper presents a specific methodological approach to assess countries´ vulnerability to ageing. Now, I am by no means disqualifying the source but still my scientific alarm bells ringing, at least just a a bit. My point is simply that I do not want to take the paper's method and approach at face value. I have pasted the report's conclusion and empirical foundation below.

basic categories, each dealing with a crucial

dimension of the challenge:

■ Public-burden indicators, which track the

sheer magnitude of the public spending

burden in each country

■ Fiscal-room indicators, which track each

country’s ability to accommodate the

growth in old-age benefits via higher

taxes, cuts in other spending, or public

borrowing

■ Benefit-dependence indicators, which track

how dependent the elderly are on public

benefits and thus how politically difficult

it may be to reduce their generosity

■ Elder-affluence indicators, which track

the relative affluence of the old versus the

young — another trend that could critically

affect the future politics of benefit reform."

(...)

Aging Vulnerability Index

2003 Edition

Rankings from Least to Most Vulnerable

Low Vulnerability

1. AUSTRALIA

2. UNITED KINGDOM

3. UNITED STATES

Medium Vulnerability

4. CANADA

5. SWEDEN

6. JAPAN

7. GERMANY

8. NETHERLANDS

9. BELGIUM

High Vulnerability

10. FRANCE

11. ITALY

12. SPAIN"

Busted Flat in Bogota

The Szeklers and the Magyars: A doomed relationship?

As it happens, a good chunk of Romania's Magyars seems to be redefining itself as non-Magyar. Recently, the leadership of a population known as the Szeklers, a Magyar-speaking population concentrated in eastern Transylvania that not only retains a distinctive sense of history but is the majority population in a large territory, has agitated for this territory to be made into an autonomous district of Romania to be known as Székelyföld. This failed, not least because of the sensitivities of Romania nationalistst to perceived Magyar expansionism. Already, at least one Internet flamewar has started because of this. What's interesting about this latest crisis in Magyar-Romanian relations is that, as suggested by John Horvath at Telepolis, the call for a Székelyföld has been made despite the Hungarian-Romanian leadership's siding with the Romanian state.

For the past couple of years, a split has emerged within the ethnic Hungarian community in Romania. The Hungarian-Romanian Democratic Alliance (RMDSZ) is the largest ethnic minority party in Romania and used to be considered the de-facto representative of Romania's 2 million ethnic Hungarians. An internal power struggle and disagreement over how best to secure minority rights in Transylvania led to a split within the RMDSZ. One faction, now independent from the main party, favours a more direct approach and direct autonomy; the RMDSZ, meanwhile, favours a more indirect approach and change from within the system.

As a a coalition partner in the present government, the RMDSZ is against the proposed declaration at Szekelyudvarhely, noting that over 16 years of political effort to initiate changed from within is being put to risk. Others, however, point out that after 16 years very little has been achieved by the RMDSZ, and that anything progressive which has been done thus far has been inadequate and usually the result of pressure coming from Brussels under the guise of EU membership, and not the result of the RMDSZ's efforts.

If the Székelyföld became an autonomous district of Romania, perhaps on the model of Catalonia as some have wistfully suggested, the situation for Magyars outside of the Székelyföld would become serious. The Magyars in Slovakia form a coherent majority population in areas close to the Hungarian border, while the Magyars in Vojvodina form another like coherent pocket that could one day become a proposed controversial Hungarian Regional Autonomy. Outside of the Székelyföld, Magyars form a minority vulnerable to assimilation, via individual assimilation, growing Magyar-Romanian intermarriage, and perhaps economic migration to a Hungary steadily advancing into the First World. The Szeklers don't seem to care, not especially. Why? It seems as if, in a democratic Romania where individual rights are generally secure and the Romanian state has to concede minority groups a certain amount of space, the Szeklers don't feel particularly bound to the fate of the Magyars with whom they share a language and the memory of a shared state.

The disassociation of closely related ethnic groups united by some shared features but separated by identities isn't new in central Europe. To Hungary's north, the Czechs and Slovaks have disassociated peacefully despite their cultural similarities; to Hungary's south, the South Slavic peoples of Yugoslavia managed the same task with much more bloodshed. It's rare enough for a minority group to do this, though. The situation bearing the closest similarity to the Szeklers' is that of the Acadians, a Canadian Francophone group concentrated in eastern Canada which traces its origins to a French colony with a separate history from the main French colony in Québec, and which has felt at leisure to distinguish itself from its Québécois neighbours once its fate has been secured by the expansion of official bilingualism. Romania is still far from attaining Canada's debatable level of interethnic peace but it isn't nearly as far as it used to be under Ceaucescu. Assuming that these positive trends continue in the years to come, the split between the Szeklers and the other Magyar-speakers of Romania may only widen, weakening the community's bargaining power at the national level and introducing interesting new dynamics into Hungarian-Romanian state relations. Perhaps ironically, the call for a self-governing Székelyföld might be the thing to do the most for Romanian state unity after the Cold War.

Thursday, April 13, 2006

Emigration: the private vs. the public domain

I wonder how this would compare with countries like Denmark or Germany. Too bad they didn´t include a list of the countries most people favour (Australia? Scandinavia? Belgium? etc..). It would have been interesting to compare emigrant conceptions with the actual situation on the ground. Also, what would happen if instead of a perception change the public domain was really negatively affected for some reason (significant cuts in the welfare state, taxes, insecurity etc..)?

To understand emigration from high-income countries we focus not only on factors that refer to individual characteristics, but also on the perception of the quality of the public domain, which involves institutions (social security, educational system, law and order) as well as the ‘public goods’ these institutions produce: social protection, safety, environmental quality, education, etc. Based on data about the emigration intentions of the Dutch population collected during the years 2004-2005 we conclude that besides traditional characteristics of potential emigrants – young, single, male, having a network in the country of destination, higher educated, seeking new sensations - modern-day emigrants are motivated not so much by private circumstances but by a longing for a better public domain. In particular, emigrants are in search of a better quality of life as approximated by the presence of nature, space, silence, and a less populated country. To gauge the effect of the quality of the public domain, a counterfactual scenario is offered, which suggests that a perception of severe neglect of the public domain substantially increases the pressure to emigrate. Under this scenario, approximately 20 percent of the Dutch

population would express an intention to emigrate.

Older Workers In The UK Continue Working

This news from the FT today is very interesting indeed:

More than half the jobs created in the past year were filled by people above the state pension age, according to official statistics.

The rise in the number of working older people reflected increasing financial pressures created by pensions shortfalls and a growing willingness of employers to take on older staff, employers’ organisations said.

The employment rate for “pensionable” workers, men aged 65-plus and women aged 60-plus, ranged between 7.5 per cent and 8 per cent for most of the 1990s but rose to 10.4 per cent during the three months to the end of January, according to the Office for National Statistics.

John Philpott, an economist at the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, said that concerns over pensions and increasing longevity were forcing people to recognise that they needed to work longer.

Sam Mercer, director of the Employers’ Forum on Age, is quoted to the effect that employers faced with skills shortages were also more prepared to hire older people who were physically and mentally fitter than previous generations. Interestingly the kind of jobs they are taking may be grouped more around the less skilled pole of the labour market, such as supermarket work, were there may well be less deterioration with output as people age. Dave Altig (at MacroBlog) has been drawing attention to a similar tendency in the US labour market (and this one). As he says:

"Was it the exceptionally good economy of the latter 1990s that prompted such a burst of later-life job-market activity? Not likely -- unless you want to concede that the last four years have been particularly attractive for job seekers as well (or at least older ones). Better, I think, to look for a smoking gun. Here's a candidate: The increases in the eligibility age for full social security retirement benefits (legislated in 1983), which affected its very first set of folks in the 55-and-over club in 1993, and every subsequent wave of AARP-eligible workers since (in increasing measure)."

And in this post here Dave looks at the related topic of teenage labour force participation rates, and argues that the decline may have nothing whatsoever to do with a supposed 'weak labour market', and much more to do with more and more US teenagers seeking more and more education, something which is entirely consistent with the long run decline in adolescent pregnancies in the United States highlighted here.

In conclusion some more details from the FT about UK trends:

The number of people of pensionable age in employment rose to 1.13m during the three months to the end of February; up 85,000 on the corresponding period 12 months ago.

That accounted for more than half the total rise of 147,000 in the number of people in employment. There was also a strong increase in employment among people aged between 50 and pension age, which rose by 57,000.

The biggest numerical increase in employment was in the 35- to 49-year-old age group, where the number of people with a job rose by 118,000 to 10.92m.

By comparison, employment figures for younger people fell by 13 per cent for 16- and 17-year-olds and by 0.7 per cent for the 25-34 age group.

Update

As Claus points out in comments, New Economist has a post on the same issue here. In particular he draws attention to this:

A 2005 study by the John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers University said that most baby boomers think traditional retirement is obsolete. The survey found that more than two-thirds of workers in that generation expected to work after the traditional retirement age; 15 percent anticipated starting their own business after retirement; and 13 percent expected to stop working entirely. The study reported that the number of workers saying they would never retire rose to 12 percent in 2005 from 7 percent in 2000.

Sunday, April 09, 2006

Demography and Religion in India

There has been some debate in comments about the role of religion in influencing the numbers of children that people actually have. Globally the evidence is very contradictory. Here in Europe those societies which might be thought to be among the more religious traditionally - Italy, Spain, Poland - now have lowest-low fertility levels, while, of course, secular France and Sweden have rather higher fertility. In the US many feel that the presence of large numbers of practising believers exerts an influence, yet, as I am often at pains to point out, one of the principal reasons why some US women have rather more children is that they start early, indeed very early, in adolesence. I find it difficult to square teenage pregancy with especially devout behaviour, but then maybe that is just me.

Now from India comes some in depth research from Sryia Iyer and her book, Demography and Religion in India. She aksks the question do religious beliefs significantly affect demographic behaviour, and her answer seems to be an unequivocal no. The important issue is, as we find time and time again, access to education. As the abstract states:

This book asks: Do religious beliefs significantly affect demographic behaviour? It examines the theological content of Islam and Hinduism in the context of population growth. It also offers quantitative evidence that religious differences in fertility and two of its proximate determinants, contraceptive choice and the age at marriage, are in fact, due to differences in socio-economic characteristics, such as access to education. The econometric analysis is based on fieldwork carried out among Hindu, Muslim, and Christian women in India. The determinants of women's age at first marriage, their contraceptive choices and their fertility are modelled and then analysed, drawing inferences for population policy.

Saturday, April 08, 2006

Latino Migration: A Tale of Two Industries?

Well Latinos are in the news again this week. There are estimated to be some 11 million undocumented Latino migrants currently living and working in the United States, and what to do to resolve this situation is clearly a major headache for the current republican administration. But beyond this, the huge and extended flow of migrant workers into the US is changing the demographic face of the country. So first-off let's take a look at some reality-check factoids:

Now according to Rogelio Saenz at the Popoulation Reference Bureau:

"Significant changes have taken place over the last decade in the racial and ethnic composition of births in the United States. Latinos (also known as Hispanics) are now accounting for an increasing share of U.S. births, while major racial and ethnic groups account for a decreasing share. These trends mean that, by 2030, one in every five U.S. residents will be Latino...."

(So here is point number one, there are more and more Latinos, and they are changing the racial and ethnic composition of the United States).

"Although the significant rise of Latino births has taken place across the country, the most dramatic increases have occurred in new destination states for Latinos. While these states (primarily in the Midwest and South) have historically had relatively few Latinos, their growing numbers of jobs in agriculture, construction, and meat processing are now attracting Latinos, especially Mexicans."

So then come points two and three, the destination distribution of the new population is now in the process of changing (with more and more migrants moving to non-traditional destinations) and there is a large concentration of (male??) Latino migrants in two principal industries: construction and meat processing.

"These dynamics meant that the number of births to Hispanic women in the United States increased by 39 percent between 1993 and 2003, compared to an overall increase of only 2 percent among all births in the country during the same period. Indeed, the share of births in the United States to Latinas increased noticeably between 1993 and 2003, from 16 percent to 22 percent. Meanwhile, the share of white births declined from 62 percent in 1993 to 57 percent in 2003, and that of African American births dropped from 16 percent to 14 percent."

So this is point four, Latino births in 2003 accounted for 22% of total US births. (In fact vital statistics for 2003 indicate that of all births for that year nearly one quarter of the total were to women born outside the United States).

Now returning to the employment distribution of Latinos, Emilio Parrado and William Kandel in a new paper - New Hispanic Migrant Destinations: A Tale of Two Industries) - inform us that:

Since 1990, Hispanics have grown dramatically in both rural and urban non-traditional receiving regions, especially in the Southeastern United States.1 Between 1990 and 2000 the Hispanic proportion in metropolitan areas of the Southeast grew from 11 to 14 percent while declining from 61 to 58 percent in the Southwest (Kandel and Parrado, 2005). In the cities of Atlanta and Raleigh-Durham, for instance, the Hispanic population grew by an extraordinary 362 and 569 percent, respectively, compared to 27 and 30 percent for Los Angeles and San Antonio......

Rural areas exhibit an even more pronounced trend. Between 1990 and 2000 Hispanic growth in rural areas (67 percent) was higher than in metropolitan areas (57 percent). Again, the change has been particularly acute in the Southeast. Census 2000 data indicate that during the 1990s the percent Hispanic in the nonmetropolitan Southeast increased from 11 to 19 percent while decreasing from 66 to 53 percent in the Southwest. To cite three not atypical examples, the entire populations of Franklin County, Alabama; Gordon County, Georgia; and Le Sueur County, Minnesota increased by 12.3, 25.8, and 9.4 percent, respectively, between 1990 and 2000. For Hispanics, the corresponding figures were 2,193, 1,534, and 711 percent.

Now as the authors indicate a variety of explanations have been proposed for this significant diversification of Hispanic migrant destinations. One theory has been policy oriented and argues that such diversification was the unintended consequence of the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), which legalized the status of an earlier generation of some 3 million undocumented migrants, whilst at the same time increasing the level of border crossing enforcement in a way which may have caused Mexico-U.S. migration flows to fan out beyoned the previously limited range of well-traversed crossing points on the northwestern border towards numerous, more neglected, southeastern portions of the border.

Ironically, as Massey and his colleagues suggest, this 'tightening of security' policy may have had the unintended consequence of turning more temporary migrants into permanent ones by making it more costly and arduous for them to come and go.

However another possible explanation for the diversification could be found in the dynamics of the US labour market itself. As Parrado and Kandel argue such movements may be best understood in connection with industry and labor demand changes in receiving areas which attract the migrants. As they point out, in developed societies, labor markets tend to bifurcate into a capital intensive primary employment sector offering long-term, secure jobs with higher wages and potential for economic mobility, and a labor intensive secondary sector that provides little long-term opportunity, little employment security, or little meaningful economic mobility. (This is the so-called dual labour market theory, originally advanced by Michael Piore in the late 1970s). The employment instability, seasonality, occupational immobility, and overall poor job quality of the secondary sector implies that firms needing to expand their labour forces face considerable obstacles to satisfy labour demand with domestic labour supply (because native born workers are often reluctant to take the kind of jobs offered), hence employers often have recourse to immigrants (regular or irregular).

As the authors say:

"Immigrants solve the quandary of flexible low-wage employment recruitment because their transnational status permits them to profit economically through the arbitrage of destination country wages to home country standards of living, and their social frame of reference in home countries ameliorates their unstable condition and low social status in destination countries."

"This perspective implies that in order to understand the diversification of Hispanic migrant urban and rural destinations closer attention must be directed to processes of employment growth, relocation, and overall transformation of industries in the secondary sector since it is the generation of jobs especially tailored to migrant populations that drives migration flows."

So immigrants are a near-perfect labour market solution, and this tells us why they come. But what about where? Well, Parrado and Kandel argue that there are two distinct processes at work inside the US which are relevant here. The first is an internal movement of relatively well educated native born Americans towards what William Frey has called the “New Sunbelt” (eg Georgia, North Carolina, and Arizona). These new populations need housing, and this fuels a construction industry boom, which of course thrives on migrant workers.

The second factor is industrial restructuring, especially in the meat processing industry (beef, pork, and poultry products). This restructuring has had two consequences: the increasing location of production facilities to rural areas, mainly in the Midwest and Southeast and a decline in the relative attractiveness of meat-processing jobs. (As someone who readily recognises his limited knowledge of the internal structure of the US economy, I can't help thinking at this point: why are there so many people involved in the meat processing industry? Is a significant part of this production destined for export? Do the meat producers benefit from subsidies? Are migrants being attracted only to re-export what they produce, possibly even to the very countries in which they originate).

Again as the authors conclude, to the extent that rural areas attract and get involved in activities like meat processing they can expect growing Hispanic populations or, put another way, economic processes and policies which fuel the growth of manufacturing employment in rural areas are more than likely destined to likely to change the ethnic composition of these same areas, and of course, in so doing, change the future face of the United States.

References

Frey, W. H. 2002. “Metropolitan magnets for international and domestic migrants.” The Brookings Institution. Washington, DC.

William H. Frey, “Diversity Spreads Out: Metropolitan Shifts in Hispanic, Asian and Black Populations Since 2000” Washington DC: Brookings Institution, Metropolitan Policy Program. (March, 2006)

A collection of William Frey articles can be found here.

Piore, M. J. 1979. Birds of Passage: Migrant Labor and Industrial Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thursday, April 06, 2006

Danish Population

Well, maybe this is just one way of saying that Claus is doing some guest posting over at A Fistful of Euros. The principal theme of Claus's firt post is flexicurity and the Danish labour market model, but the issue of migration in and out of Denmark has rapidly emerged in the comments. This, of course, got me digging around.

Now for all the proclaimed openness, I have to say that I didn't find the Danish statistics office site among the most user friendly I have come across of late. Nonetheless there is a micro-database, and if you ask the right questions you can get the answers you are looking for. Like migration for q4 2005: immigrants 9,869, emmigrants 10,076, net-migration thus was a negative outflow of 207 people. This needs to be put in the context of a population which now has very slow natural growth (1,637 in q4 2005). Now these numbers may seem comparatively small, but they need to be contextualised by the fact that Denmark is a comparatively small country (total popn q4 2005 5,425,420).

And it should be remembered that Demarks population continues to age. Here's the age pyramid for 2000.

One way of reading this pyramid is that Denmark seems to have begun birth postponement about thirty five years ago (around 1970, the first purple line). This continued steadily till about 15 years ago (the yellow, minimum recent generation, line). Then two things happen, displacement continues, but those who have been postponing start having the delayed babies, hence there is a small rebound, before the generational reduction set in again.

Now, looking at all this in the longer term, according to the latest version of the CIA factbook Denmark has a median age of 39.47 and a fertility rate of 1.74 (TFR), which means that if the migration flow doesn't start to invert, and to a significant extent, Denmark's population will soon start to decline.

All of this raises the same issue that Thomas was discussing in this post, about the growing phenomenon of emmigration from Germany: will there be winners and losers in the immigration game. Will some countries be net winners, and others net losers? And without wishing to politicise this post especially, don't those countries which are failing to attract significant inward migration need to ask themselves what it is which makes them unattractive as an end destination?

Links II

May I suggest you to add a link to our institute (Institut nacional d'études démographiques or for English readers). Among other things, you may find of special interest our electronic 4-pages monthly Journal Population and societies. The last issue published in english, on "Birth prevention before the era of modern contraception" has been written by Etienne Van de Walle, a great demographer who suddenly died last month. Half of our issues deal with international themes.

Thanks Laurent, I have now updated the sidebar. Also, S N Stirling points out in comments that the 2006 update to the CIA World Factbook is now online and this is now in the statistics section of the sidebar, as are links to population statistics for Turkey, Singapore and South Korea (there is no particular order here yet, they get added as I find the time and the inclination).

Links I

The relevant report is this one: Report of the Secretary-General on world population monitoring, focusing on international migration and development (Agenda item 3 on the page linked above). The session is essentially to prepare the following meeting:

High Level Dialogue on International Migration and Development United Nations General Assembly, 14-15 September 2006.

Both the dialogue meeting and the report are going straight into the sidebar. I will blog separately about the contents of the migration report when I have read it and when I have the time to do so. (Incidentally, the sidebar is, as I keep saying, a work in progress, my next step will be to organise some category links like ageing, sensecence, immigration, birth postponement,HIV/Aids, low fertility trap etc, please keep the links coming, thanks).

Wednesday, April 05, 2006

Sidebar Matters II

There are a number of pages with discussion on key topics (such as population ageing) as well as some thoughts on topical demographic features (e.g. this page on the baby boom). The site also provides links to other sites where demographic and other data may be obtained.

Migration and Population Growth

International migration may soon account for almost all population growth in the developed world according to a United Nations study prepared for this weeks meeting of the Commission on Population and Development (I can't find a link to the study itself, if anyone else can please post in comments):

The reports suggests there are:

191m migrants globally, up from 175m in 2000 and 155m in 1990. That represented a slowdown in growth compared with the 15-year period between 1975 and 1990, which saw 41m new migrants. But between 1990 and 2005, 33m out of 36m migrants moved to the developed world, with the US alone gaining 15m and Germany and Spain each accounting for 4m.

“The developed world continued to gather a larger share of the world’s migrants, from 53 per cent in 1990 up to 61 per cent in 2005......Today, one in every three migrants lives in Europe and about one in every four lives in northern America.”

Obviously it will be really interesting to see the full report since the aggregate numbers cited above hide a multidue of issues, like the fact that the 4 million who went to Germany overwhelmingly went in the first half of the ninetees, while the 4 million who came to Spain came largely after 2000. As we saw in this post, Germany is now nearly a net emigrant nation. It will also be interesting to think in a bit more detail about origins, destinations and volumes of migration since 1975 if such analysis is contained in the report.

US Fertility II: Mother's Age At First Birth

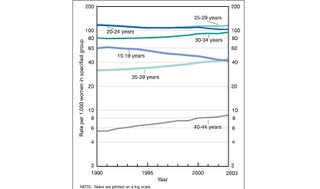

Birth Rates By Age of Mother US 1990 - 2003

Another 'stylised fact' of US fertility has been the comparatively low average first birth ages of US mothers when compared with, say, European ones. In part this has been a product of the comparatively high level of teenage pregnancy, but this is far from being the whole picture.

As can be seen from the above graph birth rates in the age bands 25-29, 30-34, 35-39 and 40 to 44 have all been rising steadily since the early 90s, while those in the 15-19 and the 25-29 groups have been falling. As noted in the last post, the decline in the 15-19 age band represents a sustained and ongoing reduction in the importance of teenage pregnancy.

The birth rate for women aged 20–24 years declined to 102.6 births per 1,000 women in 2003, the lowest rate on record. At the same time births increased among the non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, American Indian, and Asian or Pacific Islander (API) female population but decreased among non-Hispanic black women. This change in the number of births in the 20-24 population is consistent with a variety of explanations, but undoubtedly one part of the picture is an ongoing birth postponement process among the US non-Hispanic black population and possibly the initiation of one among sections of the Hispanic population. This is really only conjecture on my part, as I don't yet have data to back this up at all.

Data for this post (including the graph) come from Births: Final data for 2003. JA Martin, BE Hamilton, PD Sutton, SJ Ventura, F … - National Vital Statistics Reports, 2005 - cdc.gov

Tuesday, April 04, 2006

Economic Growth In The OCED

Claus is right to draw our attention to the OECD factbook. There is a lot of useful data to be found there. I have just found this useful graph of economic growth in the OECD since the start of the ninetees:

A number of non OECD countries have been added by the OECD - China, India, Brazil - and this makes the picture even clearer. Almost all the elderly societies - Japan, Germany, Italy, Switzerland - have been experiencing low growth, and over a comparatively long period of time. At the other end, those countries getting a boost from their demographic dividend have been having comparatively high growth (Ireland included). Including the first half of the ninetees may even blurr the contrast a little, since the situation has been most pronounced over the last decade. (Full stats on annual growth rates over this time can be found in this pdf). The situation is further complicated by the evolution of the East and Central European EU accession states, which although ageing comparatively rapidly, have been having a 'catching-up' growth boost due to their coupling with the rest of the EU. Their growth evolution will be an important area of interest in the next few years.

The evolving dependency ratio situation is also of interest.

One point which immediately stands out is how France, despite having a comparatively high (1.9 TFR) fertility rate, and the outlook of a steadily rising population, will experience fairly rapid ageing due to the life expectancy outlook and to the special shape of the existing age pyramid (check the pyramid link in the sidebar if you are interested).

This is what adds special interest to the current debates about labour market reform. The quite rapid increase in the dependency ratio means that France has to address its particpation levels and its government debt evolution sooner rather than later if it wants to remain on a sustainable path.

This article has a useful summary of the points in the factbook which are of relevance to the present debate in France.

Monday, April 03, 2006

US Fertility II: Teenage Births

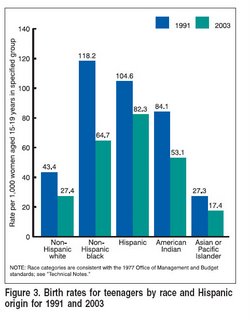

One of the 'stylised facts' of the relatively high US fertility in OECD terms has been the level of adolescent pregnancy among some groups of the population. Well it is important to note that the importance of this component is decreasing. According to CDC produced Final Births Data for 2003 the teenage birth rate in the US fell 3 percent in 2003 to 41.6 births per 1,000 women aged 15–19 years. This in fact represented another record low for the US and the rate has now fallen by a full one-third since its 1991 peak of 61.8. The rate for females aged 10–14 years declined to 0.6 per 1,000, again a one-third decline since 2000. Birth rates for teenagers 15–17 and 18–19 years each fell 3 percent. The rate for ages 15–17 years was 22.4 per 1,000, 42 percent lower than in 1991, and the rate for ages 18–19 years was 70.7 per 1,000, 25 percent lower than in 1991.

One of the 'stylised facts' of the relatively high US fertility in OECD terms has been the level of adolescent pregnancy among some groups of the population. Well it is important to note that the importance of this component is decreasing. According to CDC produced Final Births Data for 2003 the teenage birth rate in the US fell 3 percent in 2003 to 41.6 births per 1,000 women aged 15–19 years. This in fact represented another record low for the US and the rate has now fallen by a full one-third since its 1991 peak of 61.8. The rate for females aged 10–14 years declined to 0.6 per 1,000, again a one-third decline since 2000. Birth rates for teenagers 15–17 and 18–19 years each fell 3 percent. The rate for ages 15–17 years was 22.4 per 1,000, 42 percent lower than in 1991, and the rate for ages 18–19 years was 70.7 per 1,000, 25 percent lower than in 1991. According to the CDC report:

Declines in rates have been especially striking for black teenagers: their overall rate dropped 45 percent since 1991, whereas the rate for young black females 15–17 years has plunged more than half. Rate declines for all teenagers were substantial enough to more than compensate for the increased number of female teenagers, so that the number of births to women under 20 years dropped to the fewest since 1946, the first year of the baby boom.

Data for this post (including the graph) come from Births: Final data for 2003. JA Martin, BE Hamilton, PD Sutton, SJ Ventura, F … - National Vital Statistics Reports, 2005 - cdc.gov

Sunday, April 02, 2006

US Fertility I

This post needs to be read in association with the agenda outlined in my last post. Basically I have been arguing on this blog that the US derived Total fertility Rate is a composite statistic being derived from three separate fertility regimes. Commenter SM Sterling points out that, of course, any taxonomic system is to some extent arbitrary, and that you could multiply this number considerably, it is simply that I am not convinced what positive advantage would be achieved by doing so).

Conventionally, for example over at the Population Reference Bureau, these regimes are defined ethnically:

One explanation for the higher U.S. fertility is that many European countries have racially homogeneous populations compared with the United States. In the United States, fertility rates differ among the nation's varied racial and ethnic population groups. In 1998, the U.S. TFR of 2.1 children per woman was made up of several different rates: non-Hispanic white, 1.8; black, 2.2; American Indian, 2.1; Asian and Pacific Islander, 1.9; and Hispanic, 2.9.

This is certainly part of the picture, and the united states is certainly more diverse than many EU societies. But is it as simple as this. I tried to have a first shot at this problem in this post. Basically I think, as I argue that that the impact of the most recent wave of immigration on current US fertility has been huge, but immigration is not the only pertinent factor here.

Basically, as I say there are three regimes:

1) A regime which follows the 'European Pattern' of steadily rising educational levels, increasing life expectancy and declining fertility. I say 'European Pattern' since of course this trend is being follwed increasingly in Asia, and, as many have noted, in Western Turkey and Iran (to name but some). There is nothing especially 'ethnic' about all this, it is simply a product of one path of economic development.

2) A regime which is based on high rates of school dropout, unstable partnerships, and frequent adolencent pregnancy. Since this regime, in one form or another, can be found in the UK and Ireland it has been called an 'anglo' regime, but, of course the Irish are Celts, so again ethnic labelling fails us. The parts of the Afro American population also appear to follow this profile.

3) The hispanic regime. This is a relatively high-fertility regime (around 2.8 TFR and falling), but appears to combine many of the features of relatively higher fertility to be found in traditional societies with some of the teenage pregnancy, school dropout unstable partnership patterns which characterise the second regime. As such the rate of fertility decline to be expected here is hard to foresee.

Fertility readings for the first group may be deceptive, becuase almost certainly widespread birth postponenment has been taking place over recent decades in this group, and this, as we know, produces early statistical declines in the TFRs which later reverse as the 'missing births' occur at the higher ages. What will be very interesting will be to follow the final parities for subsequent cohorts in this group.

Also to be watched is the evolution of the third regime. It is typically a 'third world' regime, and as such may be subject to rapid downward movements in TFRs, movements which can be produced by substantial upward movements in first birth ages, just as we can see in Southern Europe or in the Asian Tigers.

Reference

On the first regime, this paper by this intriguing paper by US researchers Robert Drago & Amy Varner “Fertility and Work in the United States: A Policy Perspective” is a useful background to the pre-latest wave immigration evolution of US fertility.

US Fertilty and Growth, A Research Agenda

Possibly some could accuse me - and probably with good reason - of being obsessed with the US fertility issue (see this post which was a first pass at the issue, and this one by Claus). I think what is happening on the fertility front in the US is important for all of us since the US fertility situation is more or less unique in the OECD world, and possibly will become even more unique as an increasing number of developing countries attain below replacement (and possibly even lowest-low) ferility. The examples of the Asian tigers, China, Thailand, the Southernmost (and economically most succesful) Indian States (Kerala, Tamil Nadu) should give us serious food for thought on this count.

The US has managed, to date at least, to maintain something approximating to replacement fertility, the big question is why? The US is also (along with France and the UK) well-known as having been a host country to substantial migratory in-flows, and of course France and the UK also to-date have relatively more benign structural damage to their population pyramids. So the first question that one might want to ask would be what precise connection there is between migration and fertility?

Following on from that, the decline in fertility has been slow and long term in all three of these countries (France, the Uk and the US), so is there any connection between the slow decline and the absence of very low fertility? This would be my second question.

Also we know that those OECD countries experiencing above average growth (the US, Spain, the UK) are experiencing strong inward migration, while the higher median age societies (especially Japan and Germany) are now seeing very low net inward migration or even net outward migration. In addition the skill balance of these flows in the oldest-old societies is strongly negative. Inward migration is largely unskilled while a more highly educated and skilled population may be leaving. Are we, then, seeing non-linear consequences of overly rapid ageing in some societies while the problems posed by negative migration and fertility traps are looming in others? This would be the third question.