Robert Solow, Nobel Acceptance Speech

When the IMF said last year that Spain's unemployment level was unacceptably high, I was pretty critical of the fact that they didn't spell out the consequences of this, or offer any substantial policy alternative. The most obvious impact of this failure to find an alternative is being seen right now, with the emergence of political movements which could well turn the country's two party system completely upside down, and the steady flow of talented young people out of the country in search of work. This blog post will focus on the latter issue, and will argue that the country's participation in a currency union with no possibility of devaluing against main trading partners has the consequence that the country's economic adjustment after a massive housing bubble is being forced to take place through the demographic channel, with serious long term consequences for the economic growth rate and the sustainability of the pension system.

The Price Of Doing Nothing

The social and political risks associated with Spain having conducted a far from complete economic adjustment are now becoming apparent, but there are also long term economic consequences, ones which may not be very evident at this point. People are often too busy celebrating a short term return to growth to ask themselves the tricky question of where all this is leading.

The most obvious result of having such a high level of unemployment over such a long period of time - Spain's overall rate won't be below 20% before 2017 at the earliest - is that people are steadily leaving the country in search of better opportunities elsewhere. Initially this new development was officially denied, and since there is little policy interest in the topic we still don't have any adequate measure of just how many young educated Spaniards are now working outside their home country. Anecdotal evidence, however, backs the idea that the number is large and the phenomenon widespread. All too often articles in the popular press are misleading simply because journalists have no better data to work from than anyone else. On the other hand work like this from researchers at the Bank of Spain (Spain: From (massive) immigration to (vast) emigration? - 2013) only serves to illustrate how little we know, especially about movement among Spanish nationals.

On the other hand, when it comes to migration flows among non Spanish nationals we do have a lot better quality information due to the existence of the the municipal register electronic database. Everyone who wishes to be included in the health system needs to register with it (whether they are a regular or an irregular immigrant), and non Spanish nationals need to re-register with a certain frequency (so the authorities know if they leave).

More than an economic phenomenon, Spain's property boom was a demographic one. Since births only just exceeded deaths, between 1980 and 2000 Spain's population rose slowly, by just over 2 million people. Then between 2000 and 2009 it suddenly surged by 7 million. This was almost entirely due to immigration, with workers coming to the country from all over the globe attracted by the booming jobs market. Then in 2008 the boom came to an abrupt end, and unemployment went through the roof causing the trend to reverse. Since 2010 more people have left the country every year than have arrived, with the consequence that the population is now falling. Given that in 2015 the statistics office forecast that for the first time deaths will exceed births, it is most likely that this decline will continue and continue.

In fact the overall migration number - a net 251 thousand people emigrated in 2013 according to official data - only tells part of the story. The majority of young Spanish people working abroad are not included in these numbers (unless they have explicitly informed the Spanish authorities they are leaving, and few do this, partly because they do not consider themselves "emigrants"), but just as importantly the net balance masks very large movements in both directions. According to the national statistics office over half a million people (532 thousand to be precise) emigrated from Spain in 2013, while 285 thousand people entered the country as immigrants. So the net migration statistic covers over what are really very large flows.

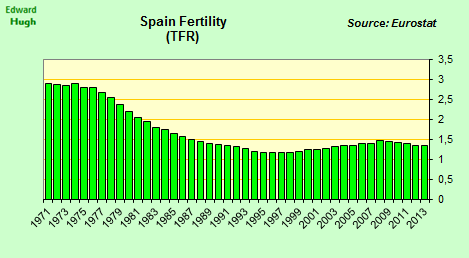

The number of annual births in Spain has been steadily falling since the mid 1970s. They accelerated again slightly in the first years of this century, partly due to the shadow effect of an earlier boom in the 1970s, and partly because the incoming immigrants had a slightly higher birth rate. Coinciding with the outbreak of the crisis births peaked again in 2008 (after an initial peak in 1976 - ie 32 years later, average age at first childbirth is now just above 30) , and now the statistics office forecast a continuous decline.

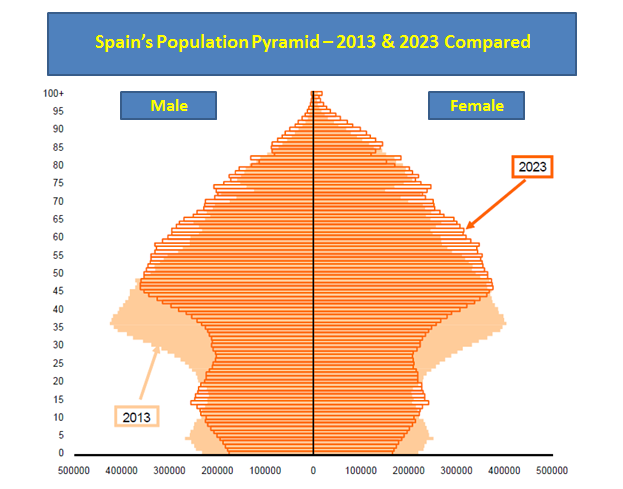

The statistics office estimate there were just 2,280 more births than deaths in the first six months of 2014, which suggests that for 2015 as a whole the balance will probably be negative, as it will be in the years to come since the birthrate is around 1.35 children per woman of childbearing age. The drill-down effect means that since every generation is smaller, and there is only a replacement rate of about two thirds, the base of the population pyramid gets smaller and smaller over time.

The current data we have for Spain show the share of the population aged 65+ currently stands at 17% (or something over 7 million people, Instituto Nacional de Estadística-INE, 2008), of whom approximately 25% are aged over eighty. Furthermore, INE projections suggest the over-65s will make up more than 30% of the population by 2050 (almost 13 million people) and the number of over-eighties will exceed 4 million, thus representing more than 30% of the total 65+ population.

International studies have produced even more pessimistic estimates and the United Nations projects that Spain will be the world’s oldest country in 2050, with 40% of its population aged over 60. At the present time the oldest countries in Europe are Germany and Italy, but Spain is catching up fast.

In their most recent long term population projections the national statistics office suggested that Spain's population would fall to 41.6 million by 2052 (a 10% drop over current levels). While the number of over 80s rises sharply the number of people under 15 is forecast to fall to just over 5 million, a drop of about 25%.

At present the rate of outward migration from Spain seems to be slowing as the economy starts to create jobs. But just how stable and sustainable is this trend? This is why the issue of whether or not Spain has taken enough measures to ensure a better longer term growth rate (a growth outlook which moves beyond picking the low lying fruit after the recession) becomes important. In the short term population projections published in November 2013 by the statistics office, Spain's population was forecast to fall by 2.6 million (5.6% of the present population) over the 2013-2023 decade. The largest population decline was expected to be in the 20 to 49 age group, which was expected to fall by 4.7 million (or 22.7%).

These are dramatic numbers, but it must be emphasized that they are very sensitive to emigration rates. For the moment the improving job market means the outflow numbers (while remaining large) are decreasing, although again it must be emphasized once more that we have very little knowledge about the actual migration rates of young educated Spanish citizens.

Whatever way you look at it this state of affairs is highly undesirable, and raises serious questions about the sustainability into the medium term of Spain's current economic recovery. If the level of unemployment is "unacceptably" high, this is partly because of the damage it will do to Spain's economic outlook in the longer term.

But won't they all come back? This is the answer I get time and time again. Such an outcome is far from guaranteed, even if it is what policymakers implicitly assume. As I am trying to suggest, whether those who are leaving come back or not depends on the state of the Spanish job market, and despite the fact jobs are now being created the size of the problem means the situation on the ground will remain difficult for many, many years to come. Some point to surveys, like the one shown in the chart below carried out by recruitment experts Hays, which show that a large majority of those leaving want to return. But wanting is not the same as being able. Few want to leave their home countries and their families to start a new life in a distant land, but many are now being forced to do so. Most initially don't see themselves as emigrants, but as time passes there is a growing possibility that that is exactly what they will become.

So What Are The Probable Economic Consequences of Doing Nothing?

What matters in Spain is not the fact that the economy is recovering. More important is how it is recovering, and how quickly the jobs market could get back to normal. Otherwise the risk exists that the longer run growth potential could fall even as the unemployment rate remains high.

It is a simple fact that as Spain's working age population falls so will the long term potential growth rate also fall. And if growth is lower, then new jobs will be less. As can be seen in the diagram below (which illustrates how EU Commission calculates potential growth rates). There are three inputs which matter a) the existing capital stock, b) labour force growth (which is a function of working age population), and productivity.

Now it is clear that as working age population turns negative (which basically happened in Spain around 2012) the dynamic also becomes negative for potential economic growth, and the only real hope of sustaining it in the longer term is via (total factor) productivity growth. But this - the "oh well, we'll raise productivity" argument - isn't as easy as it seems. The following chart which was produced by Fulcrum research based on Conference Board and IMF data and shows clearly how the trend towards lower productivity growth in developed economies is now decades long. It simply isn't credible to imagine that this trend is going to be turned around at the click of a finger.

So one of the obvious consequences of this population loss is a permanent fall in the long run trend growth rate. This situation is concealed at the moment as the very high unemployment rate means that in the short term an above trend rate of growth is possible, but this favorable situation won't last forever.

Housing Issues

The most obvious area of the economy to be affected by population decline is the housing sector. Spain has a very large stock of empty houses (well over a million, possibly two, between new and second hand), and the rate of home sales while rising is still very low.

During the boom years the fact that a very large "boom" cohort was in the household formation a group and then that a large number of immigrants arrived to set up their homes was a key factor in fueling the boom.

During 2007 474,000 new households were set up. In 2014 the equivalent figure was 117,000. Given this new dynamic it is very difficult to see how the outstanding stock of houses can be sold, how prices can recover, and how new building construction activity can take off again.

And Then, What Happens To Pensions?

Spain's pension system is on the rocks. Before the crisis it was running constant surpluses, but now the trend has reversed, and it is in constant deficit, and the shortfalls look set to stretch forwards as far as the eye can see. The policy response to this under-financing has been twofold. Under the previous socialist government the funding gap was financed out of the general government deficit, but since the arrival of the PP government it has been funded by drawing down on the Reserve Fund which is meant to ensure the long term sustainability of the system. This helps the headline fiscal deficit number, but the decline in the Reserve Fund is starting to make a growing number of Spaniards increasingly nervous.

Part of the problem the system is having is simply the result of population ageing: the balance shifts as the number of pensioners rises and the number of contributors for each pensioner falls. Another part is the result of the recent economic crisis (since with so much unemployment less people contribute) while a third contributing factor is the changes in the labour market which mean that young people earn a lot less than those retiring, leading average contributions to fall, while average pensions rise.

Some of the results of this sea change can be seen in the chart below (sorry about the Spanish, but I think the main points are easily grasped). The number of contributors for each pensioner hit a high of 2.71 in 2007, since then it has been falling and was at 2.25 in 2014. The number of pensioners has risen from 7.6 million in 2007 to 8.4 million in 2014.

The average pension paid is also rising. In February 2015 the total amount paid out by the system in pensions was up 3.1% year on year. But the number of pensioners was only up 1.3%, so the average pension went up by 2.1% due to the fact that the most recent retirees have been earning more than earlier cohorts and are thus entitled to higher pensions. We don't have data on this year's pension system income yet, but at the end of last year it was rising at about 1.5% a year, leaving a sizeable shortfall for the system to cover.

As I said, under the former PSOE the shortfall was funded out of the general government budget, and possibly 1.5 percentage points of the 9.6% 2011 fiscal deficit were the result of this financing. With the arrival of the PP in government this policy changed, and pension financing moved over to the Reserve Fund.

The attrition has been constant and the Fund is now starting to dwindle. In 2012 7 billion euros were withdrawn from the Fund, in 2013 it was 11.6 billion euros and in 2014 15.3 billion euros (or 1.5% of GDP). If you want to compare apples with apples and pears with pears, you would need to add this 1.5% of GDP to the 5.6% fiscal deficit, giving a 7.1% deficit using the same accounting criteria as 2011. Put another way the deficit has really been reduced from 9.6% to 7.1% in 3 years, hardly dramatic austerity. Instead of paying the pensions gap out of current income the government are using a credit card issued by "future pensions" to keep payments up even though the situation is obviously getting worse, meaning it will be even more difficult to pay current pension levels in the future than it is now.

As a result of all these withdrawals the Reserve Fund - which was established in 2000 and grew via the surpluses generated in the boom years - has fallen from its 66.8 billion euro peak in 2011 to the current level of 41.6 billion euros. At the moment the government have budgeted for another 8.4 billion euro withdrawal this year, but this number could easily turn out to be larger. So 2015 should close with around 30 billion euros outstanding - about 3 years more money at the current rate. It is clear that soon after the election changes will have to be made.

There was a pension reform in 2013 which was intended to address the problem making the system self financing. A complicated formula was introduced whose intention was to ensure that more money didn't go out - on a structural basis - than came in. But this was in the era when Spaniards still expected inflation as their economic default setting, so a minimum increase of 0.25% was set. Last December consumer prices were down 1.5% over a year earlier, and as a result the minimum rise was a generous "vote winning" increase of 1.75% at a time when the system itself was running at a huge loss. Something similar will happen this year, giving at least one part of the explanation as to why retail sales are doing better - in part these increased sales are being paid for with future pensions.

Madrid Fiddling While The Future Disappears Under Its Feet?

In principle, the fact that people are moving around looking farther afield for work is a good thing isn’t it? Simple economic theory suggests it should be. Indeed one of the habitual criticisms made by outside observers about the way in which the Euro currency union operated during the first decade of its existence concerned the absence of labour mobility within the region. Labour mobility as an adjustment mechanism in the face of economic shocks has been a leading topic in the economic literature on currency unions, both in the United States and in Europe. More than 50 years ago, in his seminal paper on optimum currency areas, Robert Mundell stressed the need for high labour and capital mobility as a shock absorber within a currency union: he even went so far as to argue that a high degree of factor mobility, especially labour mobility, is the defining characteristic of an optimum currency area – i.e. one that works well. Thus, a key question when evaluating whether the Eurozone is an optimal currency area has always been: how important is labour mobility as an adjustment mechanism in Europe compared with, say, the United States?

So now that people are finally moving from one Euro Area country to another in search of work the currency union is working better, isn't it?

If only life were so simple. Two issues arise in the case of labour migration within the EU that make the situation different to that of movement from one US state to another. In the first place US states are inside one and the same country. This is important when we come to think about things like unemployment benefits, health systems and pension rights. In the second place US fertility still hovers round about population replacement level (2.1 total fertility rate). In most of the countries on the EU periphery fertility levels are significantly below 1.5 children per woman of childbearing age (Tfr), and have been for decades.

More recent evidence, however, suggests that things are now changing even there with 2011/2012 marking a turning point in migration patterns and population momentum all across the southern rim. The number of newly registered migrants into Germany from Italy and Spain, for example, rose by about 40% between the first half of 2012 and the first half of 2013. The number from Portugal rose by more than 25% over the same period and since then the process has accelerated. Numbers for London and Paris reveal a similar pattern.

Since unemployment in the Euro Area currently ranges from about 5% in Austria and Germany to over 25% in Greece and Spain there is plenty of potential for imbalance adjustment. Half-a-century after Mundell’s original article was published, the most ambitious attempt yet to create a single currency spanning a wide variety of national boundaries is about to see “optimal” labour mobility. But is it really so optimal? Is it as desirable as many assume to correct imbalances between countries through working age population flows rather than through devaluation? Is there any way to evaluate outcomes? Are there hidden costs in doing it in the former rather than the latter way?

As Nobel economist Robert Solow puts it in the quote with which I start this post, it is impossible to believe that the longer term path of an economy is unaffected by the trajectory taken during periods of deviation from trend - whether upwards or downwards. Emigration, and with it negative working age population dynamics, are being promoted by the ongoing labour market crisis in the worst affected countries. The question is just how far the longer term future of these countries is being put at risk by the form in which the adjustment is taking place. In allowing this to happen instead of addressing excessive indebtedness issues, are we simply replacing short term debt defaults with longer term pension and health system ones?

Young people are moving from the weak economies on the periphery to the comparatively stronger ones in the core, or even out of an ever older EU altogether. This has the simple consequence that the fiscal deficit issues in the core are reduced, while pressures on those on the periphery are only liable to get worse as welfare systems become ever less affordable. Meanwhile, more and more young people could follow the lead of Gerard Depardieu and look for somewhere where there isn't such a high fiscal burden, preferably where the elderly dependency ratio isn't shooting up so fast.

What impact are the migration trends within the Euro Area going to have on trend GDP growth and structural budget deficits in the respective member countries in the longer term? These questions are just not being asked.

As often happens in economic matters, solutions to one problem are inadvertently promoting the creation of another. Avoiding radical debt restructuring on the periphery, and going for a "slowly slowly" correction doesn’t necessarily mean that all other things remain equal. The Euro is being held together by allowing unemployment rates to adjust towards a narrower range via population flows.

The question is, is this good news? Obviously in one sense it is, if this is needed to make the Euro work it has to happen. But there is a downside: changes in the political process are lagging well behind developments in other areas, and especially in the migration one. It has been clear since the Euro debt crisis that a common treasury was a necessity for the good functioning of the currency union, that all participants would need to make sacrifices in this regard, yet progress towards this objective has been painfully slow, and full of bitter recrimination. At the end of the day the migration problem might just the issue that brings this simmering problem right to a head. Postscript

Many of the above arguments are developed in detail and at greater length in my recent book "Is The Euro Crisis Really Over? - will doing whatever it takes be enough" - on sale in various formats - including Kindle - at Amazon.

No comments:

Post a Comment