- Old age popped up as a topic in my feed. The Crux considered when human societies began to accumulate large numbers of aged people. Would there have been octogenarians in any Stone Age cultures, for instance? Information is Beautiful, meanwhile, shares an informative infographic analyzing the factors that go into extending one’s life expectancy.

- Growing populations in cities, and real estate markets hostile even to established residents, are a concern of mine in Toronto. They are shared globally: The Malta Independent examined some months ago how strong growth in the labour supply and tourism, along with capital inflows, have driven up property prices in Malta. Marginal Revolution noted there are conflicts between NIMBYism, between opposing development in established neighbourhoods, and supporting open immigration policies.

- Ethnic migrations also appeared. The Cape Breton Post shared a fascinating report about the history of the Jewish community of industrial Cape Breton, in Nova Scotia, while the Guardian of Charlottetown reports the reunification of a family of Syrian refugees on Prince Edward Island. In Eurasia, meanwhile, Window on Eurasia noted the growth of the Volga Tatar population of Moscow, something hidden by the high degree of assimilation of many of its members.

- Looking towards the future, Marginal Revolution’s Tyler Cowen was critical of the idea of limiting the number of children one has in a time of climate change. On a related theme, his co-blogger Alex Tabarrok highlights a new paper aiming to predict the future, one that argues that the greatest economic gains will eventually accrue to the densest populations. Established high-income regions, it warns, could lose out if they keep out migrants.

Showing posts with label future. Show all posts

Showing posts with label future. Show all posts

Wednesday, March 20, 2019

Some links: longevity, real estate, migrations, the future

I have been away on vacation in Venice--more on that later--but I am back now.

Labels:

ageing,

atlantic canada,

canada,

cities,

demographics,

diaspora,

economics,

future,

futurology,

history,

islands,

links,

malta,

migration,

moscow,

nova scotia,

prince edward island,

russia,

syria

Monday, January 18, 2016

Changing world population balances, 1800 to 2100

The Russian Demographics Blog was the most recent source to link to Max Galka's remarkable map showing changing populations in the recent past and the projected future.

For thousands of years, Asia has been the population center of the world. But that’s about to change.

Asia contains 7 of the 10 most populous countries in the world, the two largest of which, China and India, each individually have larger populations than Africa, Europe, or the Americas. And as I’ve demonstrated previously, the eye-popping population density in regions such as Tokyo and Bangladesh is an order of magnitude greater than anywhere in the western world.

Two hundred years ago, the figures were even more extreme. In 1800, nearly two thirds of the world lived in Asia. And at that time China had a larger population than Africa, Europe, and the Americas combined.

Asia dominates the world population landscape, and it has for at least the last two and a half thousand years. [. . . T]he relative population sizes of Asia, Africa, and Europe have remained surprisingly constant for thousands of years. Since at least 400 BC, 60% or more of the world has lived in Asia.

According to the U.N. Population Division, the population of Africa is poised to explode during the next 85 years, quadrupling in size by 2100.

The U.N. attributes this change to two factors: Africa’s high fertility rates (African women have on average 4.7 children vs. a global average of 2.5) and its young population, many of whom will be reaching adulthood in the coming years and having children of their own.

Tuesday, November 25, 2014

Looking to the science fiction of Monica Hughes and the demographics of the future

Just this week, I've had the occasion to reread prolific Canadian young adult science fiction writer Monica Hughes' 1991 novel Invitation to the Game. I read the book back when it came out in hardcover, as a Grade 6 student on Prince Edward Island, and was impressed. I'm happy to say that the book still holds up as well, that the novel still deserves my warm memories and the awards and good reviews of others. Understandable as a prototype of the dystopias that seem to predominate nowadays in young-adult literature, Invitation to the Game is a novel that I was surprised to find provided an interesting commentary on some of the demographic issues facing us right now.

The novel starts in the year 2154, as the 16-year-old protagonist Lisse and her friends graduate from their elite private school to their jobless adult lives. There had been a population crash in the early 21st century, precipitated by pollution, and of necessity robots were made to take over much of the day-to-day routines of human society. Even after the population recovered, however, the robots remained entrenched, with the net effect of dooming most of each coming generation to unemployment. Two of Lisse's friends are lucky enough to end up employed, for a time. The remainder are exiled with Lisse to live out their lives in a "Designated Area", an urban district to which they are confined by internal passports, depending on stipends from a resentful employed minority and grey-market jobs to live. Without any hope of escaping their condition, the young graduate drift into despair until they are invited to "The Game," a mysterious but detailed virtual reality scenario that allows them to escape to another world. Eventually, they do.

This post is not a ridiculous post about space colonization being a solution to issues of unemployment and underemployment, to marginalization and anomie. Any kind of program of space colonization is no kind of answer at all to these issues. Author Charlie Stross' 2007 essay "The High Frontier, Redux" makes the point that, even if there are economically exploitable resources in space, the optimistic dreams of human settlement are unlikely to be realized because human beings are just too fragile to persist. Many things would have to change radically for this to happen, and we don't even know if these radical changes are possible.

This is, however, a post that's concerned about the ethics of this. In this world, as in Hughes' fictional future world, people are a resource. In many parts of the world, people are an increasingly scarce resource, especially people belonging to particular demographics or possessing certain skills. Despite the value of people as a resource, and despite these local scarcities, in many cases people are being prevented from being useful. This might be because of barriers to migration. This might be because of mistaken government policies that prevent others from realizing their talents. Whatever the precise cause, it's fundamentally ill-thought and--I'd suggest--in many ways quite wrong. As Hughes' characters note, this kind of waste might even be very problematic for the survival of any numbers of regimes.

"[I]t seems the Government's not interested in any new ideas."

"That's the problem with this society," Trent interrupted. It is uninterested. Dead in the water. We should scrap it and start over."

"How?" Karen asked, her big voice booming. "Societies tend to go on until they run down by themselves or rot from inside."

"Can you afford to wait that long?" Trent pushed his sharp face aggressively at Karen. "I can't." (13-14)

When considering demographic issues, now and in the future, it's also worth considering the extent to which particular treatments are, or are not, sustainable. Various marginalizations--keeping people out, keeping people down--might be politically convenient, but they might equally be politically dangerous.

Labels:

demographics,

economics,

future,

labour market,

migration,

popular culture

Tuesday, March 27, 2012

What effect would near-term democratization in China have on Chinese demographics?

China Daily and Spiegel Online and Canada's Sun Media empire are just a few of the Western news sources that have been making claims that well-off Chinese are seeking to leave their country in large numbers, hoping to find safer, stabler places to live. Wieland Wagner's Spiegel Online article is typical.

Though the room is already overcrowded, more listeners keep squeezing in, making it necessary to bring in additional chairs for the stragglers. Outside on the streets of Beijing, the usual Saturday afternoon shopping bustle is in full swing. But above the clamor, in the quiet of this elegant office high-rise, the audience is intent on listening to a man who can help them start a new life, one far away from China.

Li Zhaohui, 51, turns on the projector and photographs flicker across the screen behind him. Some show Li himself, head of one of China's largest agencies for emigration visas, which has more than 100 employees. Other pictures show Li's business partner in the United States. Still others show Chinese people living in an idyllic American suburb. Li has already successfully arranged for these people to leave the People's Republic of China.

Li's free and self-confident way of speaking precisely embodies the Western lifestyle that those in his audience dream of. Originally trained as a physicist, Li emigrated to Canada in 1989. In the beginning, he developed microchips in Montreal, but he says he found the job boring. Then he found his true calling: helping Chinese entrepreneurs and businesspeople escape.

Of course, Li doesn't use the term "escape." Emigration from China is legal and, with its population of 1.3 billion, the country certainly has enough people left over.

Likewise, hardly anyone in the audience is actually planning to burn every bridge with their native country. Almost everyone in the room owns companies, villas and cars in China.

Many of them, in fact, can thank China's Communist Party for their success. But along their way to the top, they've developed other needs, the kind only a person with a full stomach feels, as the Chinese saying goes. It's a type of hunger that can't be satisfied as long as the person is living under a one-party dictatorship.

These people long to live in a constitutional state that would protect them from the party's whims. And they want to enjoy their wealth in countries where it's possible to lead a healthier life than in China, which often resembles one giant factory, with the stench and dust to match.

These longings have led many people in China to pursue foreign citizenship for themselves and their families. The most popular destinations are the US and Canada, countries with a tradition of immigration. "Touzi yimin" are the magic words Li impresses tirelessly upon his listeners. Loosely translated, it means "immigration by investment."

There have even been reports that large numbers of hopeful immigrants have been hoping to take advantage of Québec's immigration policy by learning French in large numbers.

Is the sort of emigration described, of well-off people seekng not so much economic opportunity as a better environment, potentially significant? Very much so. China may well be on the cusp of multiple sudden transitions, including political ones. The purge of Chongqing Communist Party chief Bo Xilai is one of the more notable events, helping to give credence to the false rumours of a coup inadvertantly amplified by the sort of heavy-handed censorship of Chinese microblogs that made people suspect something is up. Could China even be on the verge of democratizing? Who knows, but a recent post by Daniel Drezner at his blog suggested that premier Wen Jiabao might be interested in revisiting the official verdict on the Tiananmen Square student protests in 1989 before his tenure is up. Drezner was suspicious of this rumour, since apparently it has been in circulation for a while, but he still thought it worth noting. Why?

The omitted argument is a bit tangential, but bear with me. It relates to this Keith Bradsher story in the New York Times about China's relaxation of foreign capital strictures[.]

Both the inward rush of capital and the capital flight by affluent Chinese are interesting. They could force the central government to start making credible commitments with respect to property rights. Only such commitments will ensure that the locally wealthy Chinese will not immediately have their capital move to the exit whenever possible. Oddly, Wen deciding to open up Tiananmen might be a way of signaling to investors that Beijing intends to be a bit kinder and gentler than it's been over the past decade.

The international diversification of China's wealthy elite has another effect. Via Erik Voeten, I see that John Freeman and Dennis Quinn have a new paper in the American Political Science Review that concludes, "financially integrated autocracies, especially those with high levels of inequality, are more likely to democratize than unequal financially closed autocracies." Why?

[M]odern portfolio theory recommends that asset holders engage in international diversification, even in a context in which governments have forsworn confiscatory tax policies or other policies unfavorable to holders of mobile assets. Exit through portfolio diversification is the rational investment strategy, not (only) a response to deleterious government policies. Therefore, autocratic elites who engage in portfolio diversification will hold diminished stakes in their home countries, creating an opening for democratization.

Freeman and Quinn might as well be talking about China right now. Soo.... maybe the "princelings" are less worried about democratization than they used to be.

Certainly China has reached a level of economic development, as measured by GDP per capita, where a more democratic order is likely to be enduring. Certain suggestive correlations have been noted by other observers.

Looking at 150 countries and over 60 years of history, [Russian investment bank Renaissance Capital] found that countries are likely to become more democratic as they enjoyed rising levels of income with democracy virtually ‘immortal’ in countries with a GDP per capita above $10,000.

” Only five democracies above the $6,000 income level have died. Even democracies above the $6,000 level have a 99 percent chance of sustaining their political system each year. The only exceptions were the military coups in Greece in 1967 ($9,800), Argentina in 1976 ($8,180) and Thailand in 2006 ($7,440), and the events in Venezuela in 2009 ($9,115), as well as Iran in 2004 ($8,475),” RenCap global chief economist Charles Robertson writes.

The $6,000 per capita GDP seems to be a crucial level, marking the point where a country is likely to shift to democracy. Tunisia, which early this year triggered the wave of uprisings against autocracy across the Arab world, recently crossed that threshold.

[. . .]

According to Robertson, China has just entered a most dangerous political period, with per capita GDP at $6,200 in 2009. Even assuming 9 percent annual growth in per capita GDP, the country will remain in the most dangerous $6,000-10,000 range until 2014.

“The Communist Party of China is right to fear a revolution, and history suggests it will be lucky to avoid democracy by 2017, assuming per capita GDP has reached $15,550 by then,” he adds.

What impact would democratization have Chinese international migration? In post-Communist Europe the end of Communism made large-scale migration from post-Communist Europe to points around the world possible, but that model doesn't apply very well to a China that's been more successfully integrated into the wider world than any of the European Communist states. If there was a shift to a more democratic government in China, conceivably it could stem the migration of well-off Chinese seeking security that's been described recently in the Western press. If a democratic transition is triggered by an economic shock--not unimaginable, since economic shocks (like, say, a bursting of the Chinese real estate bubble?) often triggered democratic transitions, as in Mediterranean Europe, Latin America, and the former Soviet bloc--there could be more emigration notwithstanding increases in security.

All this occurs in the context of China's ongoing significant demographic changes, as described by Nicholas Eberstadt in a Swiss.Re essay from last year. Below-replacement fertility, the impending decline of China's working-age population and rapid growth of its seniors, the hollowing-out of rural areas to the benefit of urban ones, the surfeit of unmarriageable young men, the shift from the traditional extended family to somethiing closer to the Western nuclear family ... Rapid political and economic shifts would only complicate things further.

Does anyone have any ideas as to what might happen to Chinese demographics in the event of a radical political shift? I'm opening up the floor to everyone, here: it strikes me as a significant question that has not, however, been examined in significant detail.

Though the room is already overcrowded, more listeners keep squeezing in, making it necessary to bring in additional chairs for the stragglers. Outside on the streets of Beijing, the usual Saturday afternoon shopping bustle is in full swing. But above the clamor, in the quiet of this elegant office high-rise, the audience is intent on listening to a man who can help them start a new life, one far away from China.

Li Zhaohui, 51, turns on the projector and photographs flicker across the screen behind him. Some show Li himself, head of one of China's largest agencies for emigration visas, which has more than 100 employees. Other pictures show Li's business partner in the United States. Still others show Chinese people living in an idyllic American suburb. Li has already successfully arranged for these people to leave the People's Republic of China.

Li's free and self-confident way of speaking precisely embodies the Western lifestyle that those in his audience dream of. Originally trained as a physicist, Li emigrated to Canada in 1989. In the beginning, he developed microchips in Montreal, but he says he found the job boring. Then he found his true calling: helping Chinese entrepreneurs and businesspeople escape.

Of course, Li doesn't use the term "escape." Emigration from China is legal and, with its population of 1.3 billion, the country certainly has enough people left over.

Likewise, hardly anyone in the audience is actually planning to burn every bridge with their native country. Almost everyone in the room owns companies, villas and cars in China.

Many of them, in fact, can thank China's Communist Party for their success. But along their way to the top, they've developed other needs, the kind only a person with a full stomach feels, as the Chinese saying goes. It's a type of hunger that can't be satisfied as long as the person is living under a one-party dictatorship.

These people long to live in a constitutional state that would protect them from the party's whims. And they want to enjoy their wealth in countries where it's possible to lead a healthier life than in China, which often resembles one giant factory, with the stench and dust to match.

These longings have led many people in China to pursue foreign citizenship for themselves and their families. The most popular destinations are the US and Canada, countries with a tradition of immigration. "Touzi yimin" are the magic words Li impresses tirelessly upon his listeners. Loosely translated, it means "immigration by investment."

There have even been reports that large numbers of hopeful immigrants have been hoping to take advantage of Québec's immigration policy by learning French in large numbers.

Is the sort of emigration described, of well-off people seekng not so much economic opportunity as a better environment, potentially significant? Very much so. China may well be on the cusp of multiple sudden transitions, including political ones. The purge of Chongqing Communist Party chief Bo Xilai is one of the more notable events, helping to give credence to the false rumours of a coup inadvertantly amplified by the sort of heavy-handed censorship of Chinese microblogs that made people suspect something is up. Could China even be on the verge of democratizing? Who knows, but a recent post by Daniel Drezner at his blog suggested that premier Wen Jiabao might be interested in revisiting the official verdict on the Tiananmen Square student protests in 1989 before his tenure is up. Drezner was suspicious of this rumour, since apparently it has been in circulation for a while, but he still thought it worth noting. Why?

The omitted argument is a bit tangential, but bear with me. It relates to this Keith Bradsher story in the New York Times about China's relaxation of foreign capital strictures[.]

Both the inward rush of capital and the capital flight by affluent Chinese are interesting. They could force the central government to start making credible commitments with respect to property rights. Only such commitments will ensure that the locally wealthy Chinese will not immediately have their capital move to the exit whenever possible. Oddly, Wen deciding to open up Tiananmen might be a way of signaling to investors that Beijing intends to be a bit kinder and gentler than it's been over the past decade.

The international diversification of China's wealthy elite has another effect. Via Erik Voeten, I see that John Freeman and Dennis Quinn have a new paper in the American Political Science Review that concludes, "financially integrated autocracies, especially those with high levels of inequality, are more likely to democratize than unequal financially closed autocracies." Why?

[M]odern portfolio theory recommends that asset holders engage in international diversification, even in a context in which governments have forsworn confiscatory tax policies or other policies unfavorable to holders of mobile assets. Exit through portfolio diversification is the rational investment strategy, not (only) a response to deleterious government policies. Therefore, autocratic elites who engage in portfolio diversification will hold diminished stakes in their home countries, creating an opening for democratization.

Freeman and Quinn might as well be talking about China right now. Soo.... maybe the "princelings" are less worried about democratization than they used to be.

Certainly China has reached a level of economic development, as measured by GDP per capita, where a more democratic order is likely to be enduring. Certain suggestive correlations have been noted by other observers.

Looking at 150 countries and over 60 years of history, [Russian investment bank Renaissance Capital] found that countries are likely to become more democratic as they enjoyed rising levels of income with democracy virtually ‘immortal’ in countries with a GDP per capita above $10,000.

” Only five democracies above the $6,000 income level have died. Even democracies above the $6,000 level have a 99 percent chance of sustaining their political system each year. The only exceptions were the military coups in Greece in 1967 ($9,800), Argentina in 1976 ($8,180) and Thailand in 2006 ($7,440), and the events in Venezuela in 2009 ($9,115), as well as Iran in 2004 ($8,475),” RenCap global chief economist Charles Robertson writes.

The $6,000 per capita GDP seems to be a crucial level, marking the point where a country is likely to shift to democracy. Tunisia, which early this year triggered the wave of uprisings against autocracy across the Arab world, recently crossed that threshold.

[. . .]

According to Robertson, China has just entered a most dangerous political period, with per capita GDP at $6,200 in 2009. Even assuming 9 percent annual growth in per capita GDP, the country will remain in the most dangerous $6,000-10,000 range until 2014.

“The Communist Party of China is right to fear a revolution, and history suggests it will be lucky to avoid democracy by 2017, assuming per capita GDP has reached $15,550 by then,” he adds.

What impact would democratization have Chinese international migration? In post-Communist Europe the end of Communism made large-scale migration from post-Communist Europe to points around the world possible, but that model doesn't apply very well to a China that's been more successfully integrated into the wider world than any of the European Communist states. If there was a shift to a more democratic government in China, conceivably it could stem the migration of well-off Chinese seeking security that's been described recently in the Western press. If a democratic transition is triggered by an economic shock--not unimaginable, since economic shocks (like, say, a bursting of the Chinese real estate bubble?) often triggered democratic transitions, as in Mediterranean Europe, Latin America, and the former Soviet bloc--there could be more emigration notwithstanding increases in security.

All this occurs in the context of China's ongoing significant demographic changes, as described by Nicholas Eberstadt in a Swiss.Re essay from last year. Below-replacement fertility, the impending decline of China's working-age population and rapid growth of its seniors, the hollowing-out of rural areas to the benefit of urban ones, the surfeit of unmarriageable young men, the shift from the traditional extended family to somethiing closer to the Western nuclear family ... Rapid political and economic shifts would only complicate things further.

Does anyone have any ideas as to what might happen to Chinese demographics in the event of a radical political shift? I'm opening up the floor to everyone, here: it strikes me as a significant question that has not, however, been examined in significant detail.

Labels:

china,

demographics,

future,

migration,

politics

Saturday, September 17, 2011

Adomanis on Steyn: Eurabia as an oversimplified story

Writer Mark Adomanis has an extended review of Eurabia theorist Mark Steyn's latest book, the subtly-titled America Alone: Get Ready for Armageddon. Adomanis is critical of Steyn's thesis, since despite his undeniable skill as a raconteur with a good grasp for compelling narratives, it's fundamentally confused if not outright self-contradictory. The core of Adomanis' argument deserves to be quoted at length.

Admonis makes an additional interesting note at his Forbes weblog.

We've blogged here in the past about an Iran that has the sort of age structure that could drive an economic boom if the country had better government, or about the demographic transition in the Maghreb and Libya that may soon make most of North Africa a labour-importing area. (We haven't, unfortunately, written at all about a Turkey that's also well advanced in the demographic transition and has already become something of a magnet for its neighbours. Later, we promise.) If the demographic transitition from high-fertility labour-exporting demographic systems to low-fertility labour-importing systems is so far advanced in Europe's neighbours, it's not obvious how these regions will be able to take over a much larger and wealthier continent with more impermeable barriers to entry.

Steyn writes a compelling, direct story (with, agreed, an engaging style of prose): as a result of any number of bad political, economic, and social choices, the West (starting with Europe) has become fatally weakened and is going to be taken over by a civilization that is hostile to the West and antithetical to the values of liberal and conservatives alike. He writes in a time when dystopias if not outright apocalypses are pretty common, being arguably the biggest growth area in young adult fiction. The problem with his particular dystopia is that it oversimplifies things hugely.

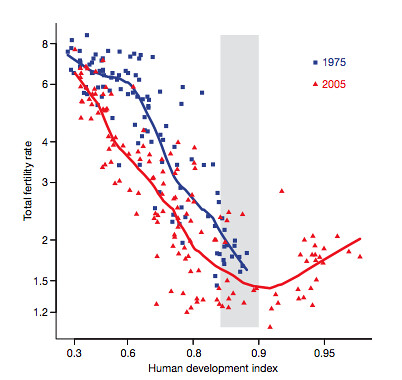

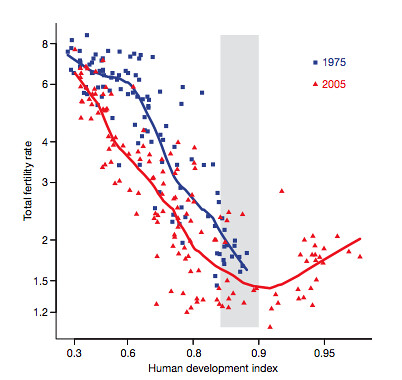

Take fertility. This graphic illustrates an argument advanced in Nature in 2009 that human development has a complicated relationship with fertility. "[T]here exists a "J-shaped" relationship between human fertility and development — i.e., that further advances in economic development can reverse the decline in fertility rate[, ...] that, in highly developed countries with HDI above 0.9, further development halts the declining fertility rates. This means that the previously negative development-fertility association is reversed; the graph becomes J-shaped." In such a case, rising human development may well lead to rising fertility as increasingly developed societies provide people with more chances to become parent to more children.

This is a contentious argument, many responding by saying that the correlation between higher human development and lower fertility merely weakens as human development rises. Is this weakening uniform, i.e. in some countries is the weakening more significant (or an actual reversal, even) than in others? I'd be interested in breaking the data apart and seeing whether the countries with the highest levels of human development might form high- and low-fertility clusters. Recent increases in fertility in northwestern Europe in the past couple of decades are at least suggestive.

This question isn't answered by Steyn, who simply wants to reverse things to a supposed ideal scenario that might not even exist. Certainly many European countries have higher rates of completed fertility than most of the North African and Middle Eastern countries that have produced large numbers of immigrants to Europe, as Europe's modernizing neighbours come to share in Europe's modern and post-modern demographic norms. It's a complex picture, and deserves to be treated in its full complexity.

The same goes for immigration. Steyn paints a picture of a low-fertility/high-immigration Europe bordering a high-fertility/high-emigration Muslim world that has been rapidly expanding to the exclusion of all other possibilities. The reality, however, is that things are much more nuanced: many emigrants from the countries supposedly directed towards Europe actually go elsewhere in the world in large numbers, differences in fertility between religious groups have narrowed consistently over time, and immigrants from the Middle East and North Africa are hardly the only immigrants moving to Europe. Europe may no longer dominate the world the way it did a century ago, but Europe--the continent as a whole, its component societies--are high-income countries with global connections that have fostered migrations as diverse as those of Ecuadorians to Spain, Vietnamese to Poland, and Sri Lankan Tamils to Norway. The story with immigration to Europe, again, is substantially more complex.

If you oversimplify a model of a real-world system you're going to come up with not an efficient model of the real world but a broken one. Eurabia as presented by Steyn is like that, no matter how compelling a storyline he weaves about it. We need higher criticism, desperately, for analyses of demographic situations of all kinds.

Steyn’s parallel attempts to prove that "statism" is the source of all of the world’s problems (from increasing obesity to stagnating median wages) and that the Islamic world, particularly Iran, is ready to run roughshod over an effeminate and degenerate West, relies on such a tendentious and selective presentation of facts that it actually winds up subtracting from his readers’ understanding of what is actually going on in the world.

According to Steyn, Europe is in a demographic death spiral caused by statism and, at a deeper level, the loss of religious belief and "civilization confidence." Iran, on the other hand, is on the fast track to becoming the dominant power in the Middle East.

Yes, in reality, in 2009, Iran’s fertility rate, which Steyn uses as a heuristic for a society’s overall health, was actually lower than that of Brazil (barely mentioned in "After America"), the United States (doomed, according to Steyn), France (even more doomed, according to Steyn), or the United Kingdom (which is well and truly f*****). If an Islamic revolution and the full-fledged implementation of hardcore Shariah enforced by "morality police" can’t keep Iran’s fertility rate from rapidly collapsing, perhaps the "problem" of declining fertility is actually better explained by the basic pressures of modernity than by the craven adoption of liberalism.

Consider the experience of Muslim countries like Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia. Despite not being "liberal" in any recognizable sense of the word (indeed, being almost the exact opposite of the coddling social-democratic "nanny states" that Steyn blames for the West’s decline), these countries all experienced sustained and rapid decrease in fertility over the past 20 years. Today, according to the CIA World Factbook, Tunisia and Algeria are below replacement rate (the number of children required to keep a population at a constant level) and several other Muslim-majority countries are right on the cusp. Steyn avoids the problems these facts present for his thesis through the simple and effective tactic of not mentioning them.

Steyn’s knowledge of demographics is remarkably confused. In the concluding chapter, for example, he argues that "much of America is now in need of an equivalent to ... post-Soviet Eastern Europe’s economic liberalization in the early nineties."

He seems unaware that fertility rates collapsed during Eastern Europe’s experiment with economic liberalization. Indeed, not a single post-communist Eastern European country has yet regained the level of fertility it had at the time of communism’s collapse: Once again, Steyn avoids the problems this presents for his thesis by simply leaving it unmentioned.

What I take away from Steyn’s sincere but confused attempt at comparative demographics is the following: He confidently predicts the future supremacy of countries (Iran) that are doomed according to metrics of his own choosing (the total fertility rate) while simultaneously making policy prescriptions (radical economic liberalization) that, when implemented in other countries, have had the effect of exacerbating the trend (decreasing fertility) he’s attempting to reverse.

Admonis makes an additional interesting note at his Forbes weblog.

[I]f, like Steyn, you consider all first-world countries to be irredeemably corrupt, and doomed by excessive debt and insufficient fecundity, what other real-world options are there? There are no free-market wonderlands where the people are rich, the government is small, and everyone is constantly popping out babies – we can only look at what actually happens in observed reality and judging by that there would seem to be (at the absolute least!) strong tensions between economic development, fertility, and political liberty.

We've blogged here in the past about an Iran that has the sort of age structure that could drive an economic boom if the country had better government, or about the demographic transition in the Maghreb and Libya that may soon make most of North Africa a labour-importing area. (We haven't, unfortunately, written at all about a Turkey that's also well advanced in the demographic transition and has already become something of a magnet for its neighbours. Later, we promise.) If the demographic transitition from high-fertility labour-exporting demographic systems to low-fertility labour-importing systems is so far advanced in Europe's neighbours, it's not obvious how these regions will be able to take over a much larger and wealthier continent with more impermeable barriers to entry.

Steyn writes a compelling, direct story (with, agreed, an engaging style of prose): as a result of any number of bad political, economic, and social choices, the West (starting with Europe) has become fatally weakened and is going to be taken over by a civilization that is hostile to the West and antithetical to the values of liberal and conservatives alike. He writes in a time when dystopias if not outright apocalypses are pretty common, being arguably the biggest growth area in young adult fiction. The problem with his particular dystopia is that it oversimplifies things hugely.

Take fertility. This graphic illustrates an argument advanced in Nature in 2009 that human development has a complicated relationship with fertility. "[T]here exists a "J-shaped" relationship between human fertility and development — i.e., that further advances in economic development can reverse the decline in fertility rate[, ...] that, in highly developed countries with HDI above 0.9, further development halts the declining fertility rates. This means that the previously negative development-fertility association is reversed; the graph becomes J-shaped." In such a case, rising human development may well lead to rising fertility as increasingly developed societies provide people with more chances to become parent to more children.

This is a contentious argument, many responding by saying that the correlation between higher human development and lower fertility merely weakens as human development rises. Is this weakening uniform, i.e. in some countries is the weakening more significant (or an actual reversal, even) than in others? I'd be interested in breaking the data apart and seeing whether the countries with the highest levels of human development might form high- and low-fertility clusters. Recent increases in fertility in northwestern Europe in the past couple of decades are at least suggestive.

This question isn't answered by Steyn, who simply wants to reverse things to a supposed ideal scenario that might not even exist. Certainly many European countries have higher rates of completed fertility than most of the North African and Middle Eastern countries that have produced large numbers of immigrants to Europe, as Europe's modernizing neighbours come to share in Europe's modern and post-modern demographic norms. It's a complex picture, and deserves to be treated in its full complexity.

The same goes for immigration. Steyn paints a picture of a low-fertility/high-immigration Europe bordering a high-fertility/high-emigration Muslim world that has been rapidly expanding to the exclusion of all other possibilities. The reality, however, is that things are much more nuanced: many emigrants from the countries supposedly directed towards Europe actually go elsewhere in the world in large numbers, differences in fertility between religious groups have narrowed consistently over time, and immigrants from the Middle East and North Africa are hardly the only immigrants moving to Europe. Europe may no longer dominate the world the way it did a century ago, but Europe--the continent as a whole, its component societies--are high-income countries with global connections that have fostered migrations as diverse as those of Ecuadorians to Spain, Vietnamese to Poland, and Sri Lankan Tamils to Norway. The story with immigration to Europe, again, is substantially more complex.

If you oversimplify a model of a real-world system you're going to come up with not an efficient model of the real world but a broken one. Eurabia as presented by Steyn is like that, no matter how compelling a storyline he weaves about it. We need higher criticism, desperately, for analyses of demographic situations of all kinds.

Labels:

demographics,

eurabia,

future,

popular culture

Saturday, January 01, 2011

Some predictions for the near future

Yesterday's post dealt with the demographic patterns of the past. What of the future?

I'm making these predictions keeping in mind what I noted in November about the huge error bars which can apply to predictions--especially but not only if they're not made conservatively. There are all kinds of feedback loops in different populations, with the selective incorporation and implementation of different cultural traits by different subpopulations, these subpopulations interacting and influencing each other in any number of unexpected fashions. I can imagine some interactions producing wildly different scenarios, unexpected surges (ro collapses) in migration and fertility and mortality and technology.

Still: Let me go out on a limb.

Reproductive medicine is going to become steadily more advanced, effective, and in-demand, as research continues encouraged by the continuing postponement and recuperation of fertility aqs a result of changing cultural mores and economic pressures. I want to write more about this next year, but suffice it to say that I think compelling reasons can be made for access to reproductive medicine as a human right, as a matter of equity.

As I've noted before, longevity is going to be interesting. On the one hand, we know the sorts of cultural and other interventions which produce not only extended lifespans but healthy lifespans--"integrated" cultures, moderation in diet, and so on; on the other hand, the growing importance of the metabolic syndrome of obesity's side-effects is going to create pressures for effective medical interventions. This may mitigate the effects of population aging by creating healthier elderly cohort better able to participate in society, thus undermining the premise of the classic dependency ratio. Whether or not cultural inclinations will change in response is another question.

There's going to be interest in any number of low fertility societies in the cultural norms of high-fertility societies, whether the American model of relatively early fertility accompanied by more classic patterns of nuptiality in an individualistic context, or the northwestern European model of relatively late fertility largely outside of traditional family contexts (common law relationships and civil unions, say) in a state supported context. Immigration can only compensate so much. Again, whether or not the changes necessary to support shifts to higher-fertility regimes will be implemented--not only government policies, but the underlying cultural attitudes towards the role of women and the composition of families--is another question. At some point change may be necessary.

The economic incentives for migration remain, and notwithstanding the shift to lower and eventual subreplacement fertility in traditional sending countries migration from relatively disadvantaged to relatively advantages regions and countries is going to continue. These migrations won't be defined solely by geography, but will be defined by cultural and historical connections and may be quite unexpected in their directions and intensities. I'll go out on a limb and expect that Poland, with its cultural ties to a poorer eastern Europe, a dynamic economy, and links to China and Vietnam, will follow Spain as an emergent and major destination for migrants from its Eurasian hinterlands.

Thoughts?

I'm making these predictions keeping in mind what I noted in November about the huge error bars which can apply to predictions--especially but not only if they're not made conservatively. There are all kinds of feedback loops in different populations, with the selective incorporation and implementation of different cultural traits by different subpopulations, these subpopulations interacting and influencing each other in any number of unexpected fashions. I can imagine some interactions producing wildly different scenarios, unexpected surges (ro collapses) in migration and fertility and mortality and technology.

Still: Let me go out on a limb.

Thoughts?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)