Friday, March 31, 2006

Brainpower: It's The Development Stupid!

Organ size seems to be a keynote topic with many people, and the brain is, of course, no exception. It has long been thought by some that bigger brains mean more cubic capacity and hence more intelligence. Would that things were ever so easy! Well today comes news of a piece of brain research which seems nicely nuanced, when it comes to brain size what matters most is not what you have but how you got it:

When it comes to brains, big is the way to go. Many studies have found a correlation--albeit only a modest one--between the size of a person's brain and various measures of mental ability. Now, a study adds a new wrinkle, suggesting that how the brain develops may be even more important to one's intellect than the organ's final dimensions.

The top scoring children had a delayed but extended cortical growth spurt, the researchers report in the 30 March Nature. In these children, who scored above 120 on the IQ tests, the cortex started out relatively thin. Then it grew rapidly, peaking in thickness around age 11 before falling off. In children with average IQ scores (around 100) cortical thickness peaked between 7 and 8 years of age.

Now anyone who knows even a smattering of Life History Theory is going to be fascinated by this. John Gabrieli, a cognitive neuroscientist at MIT is quoted as saying: "The exciting thing they suggest is that prolonged maturation is a good thing for intellectual development".

And of course:

"Whether that extended process in the highest-scoring kids is determined by genetics or is susceptible to environmental influences--parenting or teaching styles, for example--is an open question, says Richard Passingham, a cognitive neuroscientist at Oxford University, U.K."

Or indeed whether the two - the expression of the genetic and the environmental - are not in some way interconnected, indeed aren't we offering a far too limited definition of 'environment' if we restrict it here to things like "parenting or teaching styles". At this point I could go on to write an essay length post, so I think I'd better stop.

You can find the original reports on the research in this issue of Nature.

Thursday, March 30, 2006

Demographic Consequences of Shocks and Natural Disasters

Strange as it may seem this is a topic which few seem to think about. A year or so ago I posted here about this presentation by Wolfgang Lutz on his year's research at the IIASA. Since we were talking about low fertility, some wit in the comments section decided to ask me what the relevance of slides on the Tsunami were. Well if they went to this PAA session they would quickly learn. There are four excellent papers here, which it is hard to do justice to in one simple blog post.

Perhaps the issue of the migratory impact of hurricane Katrina is the one which fascinates me the most. Shortly after the disaster in New Orleans there was some speculation in the press that this would produce long-term demograohic consequences, and indeed I posted about these at the time. Well now we learn that James Elliott of Tulane University is going to try and track the process. Truly fascinating:

The proposed study will report on Phase I of a larger research project designed to track and analyze migratory behavior among New Orleanians displaced by Hurricane Katrina, which triggered the largest, most complete urban evacuation in U.S. history. While the social scientific literature on migration and urbanization has a long tradition, this genre has never before addressed such a large, unplanned social experiment as the mandatory evacuation of an entire city. The primary objectives of the proposed paper are to identify a multi-stage sample of evacuees; design and implement a survey that will collect data on their short-term migratory behavior (to be fielded in Fall/Winter 2005); and to test hypotheses about this behavior to assess how well extant theories and perspectives predict or must be amended to understand extreme scenarios of mass internal migration.

Full Paper: Tracking Migratory Behavior of Hurricane Katrina Evacuees: A Three-Stage Sample of New Orleanians, James Elliott, Tulane University

Adult Health and Mortality in Developing Countries

It is now reasonably well known that there is a steady global trend to increased longevtity. Nonetheless there are a disturbing number of case where life expectancy is falling not rising. This situation was highlighted in the 2005 Un human development report, and lead me to deploy Lant Pritchett's old expression 'Divergence Bigtime'.

Basically the question breaks down into two distinct groups of countries: some ex-member states of the old USSR, and a number of countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Some discussion of the situation in the former member states of the USSR can be found here (and here, and here).

In the case of Sub-Saharan Africa the critical importance of the impact of HIV/AIDS is also relatively well-known. Less well-known is the fact that even when this issue is discounted, mortality in some states is still rising.

A number of papers in this PAA session draw attention to this phenomenon, and try to offer some interpretation:

Adult Mortality in a Rural Area of Senegal: Trends and Causes of Death, Géraldine Duthé, Institut national d'études démographiques (INED); Gilles Pison, Institut National d'Études Démographiques (INED) (extended abstract).

Levels and Trends in Adult Background Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa, Patrick Gerland, United Nations; François Pelletier, United Nations; Thomas Buettner, United Nations (extended abstract)

Adult Health and Mortality in the Gambia: Relationships between Anthropometric Status and Adult Mortality Risk, Rebecca Sear, London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) (full paper)

The Duthé and Pison paper looks particularly interesting, as it studies mortality trends in rural Sudan. This is expecially worthwhile since, as they point out, in this area there are relatively few deaths due to AIDS, because there is a comparatively low HIV prevalence among adults:

Adult mortality in developing countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa is difficult to estimate because of the lack of reliable data. This is true for the overall level of mortality and also for mortality due to specific causes of death. In this presentation, we provide original estimates of adult mortality in Mlomp, a rural population of Senegal which has been monitored for twenty years. Though remaining at a relatively low level, global mortality increased slightly during the early '90s. In this study, we focused on the description of the causes of death among adults to determine which causes are responsible for raising the mortality level: accidents and external causes bring about many deaths among adults who work and travel, and cancer mortality appears to have increased in the last twenty years. All these causes and diseases more specifically concern men, who have higher levels of mortality than women.

Wednesday, March 29, 2006

The Obesity Epidemic: Evidence and Hypotheses

In an epoch of ever rising expectations about the increasing longevity of our lifespan what could be more appropriate than a hard look at one of the more controversial weak spots on an otherwise more optimistic horizon (I speak here obviously of the developed world, since I natural haven't forgotten the importance of HIV/AIDS and other problems like malaria which continue to dominate the agenda elsewhere). But the issue of obesity is an interesting one. Normally lifestyle and educational questions have tended to re-inforce our extended life expectations, could growing obesity represent the first serious counter tendency?

Well, here are the two papers on the agenda for tomorrow morning's session for which a summary has been posted online:

The global perspective: an increasing rate of change in obesity and key determinantsBarry M Popkin, CPC, University of North Carolina

Global energy imbalance and related obesity levels are rapidly increasing. The world is rapidly shifting from a dietary period in which the higher-income countries were dominated by patterns of degenerative diseases (while the lower and middle world were dominated by receding famine) to one in which the world is increasingly being dominated by degenerative diseases. This ppresentation documents the high levels of overweight and obesity found across higher- and lower-income countries, and the global shift of this burden toward the poor, as well as toward urban and rural populations. Among the interesting shifts examined are the differential trends in child and adult obesity and burden of obesity across the world.

Unequally Obese: Individual- and Area-Level Associations with Income Virginia W. Chang, MD, PhD; University of Pennsylvania

Although obesity is frequently associated with poverty, recent increases in obesity may not occur disproportionately among the poor. Furthermore, the relationship between income and weight status may be changing with time. We use nationally representative data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (1971-2002) to examine (1) income differentials in body mass index [BMI: weight (kg) / height (m2)] and (2) change over time in the prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥30) at different levels of income. Over three decades, obesity has increased at all levels of income. Moreover, it is typically not the poor who have experienced the largest gains.

Population Association of America 2006

Tuesday, March 28, 2006

OECD factbook 2006

The most basic yet also telling charts and conclusions can be found in this PDF.

"In 2003, OECD countries accounted for just over

18% of the world’s population of 6.3 billion. China

accounted for 21% and India for just over 17%. The

next two largest countries were Indonesia (3%)

and the Russian Federation (2%). Within OECD, the

United States accounted for nearly 25% of the OECD

total, followed by Japan (11%), Mexico (9%), Germany

(7%) and Turkey (6%).

Between 1991 and 2004, population growth rates

for all OECD countries averaged 0.8% per annum.

Growth rates much higher than this were recorded

for Mexico and Turkey (high birth rate countries) and

for Australia, Canada, Luxembourg and New Zealand

(high net immigration). In the Czech Republic,

Hungary and Poland, populations declined from a

combination of low birth rates and net emigration.

Growth rates were very low, although still positive, in

Italy and the Slovak Republic.

Total fertility rates have declined dramatically over

the past few decades, falling on average from 2.7 in

1970 to 1.6 children per woman of childbearing age

in 2002. By 2002, the total fertility rate was below its

replacement level of 2.1 in all OECD countries except

Mexico and Turkey. In all OECD countries, fertility

rates have declined for young women and increased

at older ages, because women are postponing the

age at which they start their families."

For many of our visitors this might seem very basic, but I still think some clear and worth while conclusions can be drawn.

- Fertility trends; an overall declining rate of fertility well below replacement level coupled with the postponing of birth.

- Population Growth rates; a high divergence within the OECD.

A more broader question here is that if demographics show us the real emerging economies can we use the same measure for OECD?

Tomorrow's People

Saturday, March 25, 2006

Mercedes Pascual

One of my greatest personal weaknesses - and I would be the first to recognise this - is that I hardly finish thinking about one problem before I start to get interested in another. The issue of global demography and macro economic theory is, unfortunately, no exception here. I am now in a position where I think I see some interim 'closure' (basic hypotheses, simple back-of -the-envelope models) in sight (or at least attainable in a limited time horizon), but I can also now see only too clearly that this problem forms just one part of a much bigger picture of interconnections and feedback processes. In particular these processes seem to be:

1/ Global demographic changes and their economic impact

2/ Global resource depletion

3/ Global climatic changes

This weblog is an ongoing process of exploration, but the main interface is, and will continue to be a demographic one. However it is going to be impossible to maintain a hard-and-fast frontier for something which is, by its very nature fluid.

A good example of this fluidity is to be found today in a paper which is published online this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The issue is malaria, and just how the process of global climatic change interacts with the mosquito population which inhabits the highlands of East Africa, and how changes in the mosquito population interact with the human population which shares the same habitat.

Which brings us to the work of Mercedes Pascual. As Scientific American informs us:

Since the 1970s, the highlands of East Africa have witnessed a surge in malaria outbreaks. Because the mosquitoes that carry the disease do not thrive in cooler climes some researchers have suggested a link between this rise and climate change. A 2002 study found no such connection, but a new analysis of the data--including five more years of records--seems to show that a modest increase in temperature could lead to a population boom in mosquitoes and, therefore, malaria....

Pascual and her co-workers found that "even a small increase in temperature in these locales can quickly tip the balance in the insects' favor, leading to more mosquitoes and, hence, more vectors for the malaria parasite." However caution is advisable since "this study does not prove that climate change is responsible for the increase in the malaria plaguing African highlands", it should however "be taken into account along with other factors such as treatment resistance and land-use changes".

Of course it should not escape our notice that the other two potential influences mentioned also form part of similar interconnected processes. Essentially I will be following more attentively the climatic and resource issues on my own blog Bonobo Land (and here, and here, and here), but no doubt they will inevitably from time to time 'erupt' here on Demography Matters.

Here is the research interest profile which Mercedes Pascual herself offers on her webpage:

I am a theoretical ecologist interested in population and community dynamics. My research areas encompass: (1) The spatio-temporal dynamics of nonlinear ecological systems for antagonistic interactions (predator-prey, host-parasite, and disturbance-recovery), particularly approaches to scale-up systems from small, individual, levels to more aggregated, population, levels, and approaches to incorporate implicitly in simple (highly aggregated) temporal models the effect of smaller scales. Similar questions are being addressed on the dynamics of infectious diseases in networks. (2) The response of nonlinear ecological systems to environmental variability and the application of nonlinear time series analysis to identify key environmental drivers and to predict responses. In particular, the nonlinear dynamics of infectious diseases in response to climate variability and climate change, including aspects of evolutionary change in pathogens. The main disease under study is cholera, but work is also underway on malaria and influenza. (3) The relationship between structure and dynamics in large networks of ecological interactions (consumer-resource and parasitic links).

In conclusion I would just like to cite one of the central points so often made by the anthropologist Hillard Kaplan: "life is an energy harvesting process". I think it is as simple and as complex as that.

You can find more background links to the latest paper by Mercedes Pacual and her co-workers here and here.

Information on the working group on Global Change and Infectious Disease at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis can be found here, and one of their publications can be found here.

The US National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis can be found here. Also the webpage of the "Seasonality and the population dynamics of infectious diseases" project which is lead by Mercedes Pascual and Andrew Dobson can be found here.

This paper (from 1992) by Jonathan Patz - A human disease indicator for the effects of recent global climate change - is also fairly relevant.

Finally, what is the relevance of all this for economic analysis? Well this obviously can't be answered in any satisfactory way here, but just as a clue, let's think about the UN sponsored Global Millenium Project lead by Jeffrey Sachs. I have a problem with the whole line of approach that Sachs is pushing at the moment, since I think it is hopelessly simplistic (which is a pity, since at the end of the 90s he was doing some pretty interesting work with Jeffrey Williamson on demography and development, and here). Now Sachs is pushing the health issue, and this is obviously important, but unless we get to grips with the whole damn complex situation, I fear his initiative will only lead to disappointment and yet more frustration. More posts on this to come, as and when.....

Wednesday, March 22, 2006

Health And Economic Growth

Xavi Sala i Martin concudes in his paper on growth research - "15 Years of Growth Economics: What Have we Learnt?" - had the following to say on growth and health:

"The relation between most measures of human capital and economic growth is weak. Some measures of health, however, (such as life expectancy) are robustly correlated with growth"

Now this is a topic Xavi knows something about, since, as he says in one of his papers, "I Just Ran Two Million Regressions". In other words he knows that of which he speaks, these findings are robust (and possibly the only really robust outcome of that whole generation of growth research), and health and life expectancy *do* correlate with growth.

So this paper by Marcella Alsan, David Bloom and David Canning - The Effect of Population Health on Foreign Direct Investment - seems to be directly to the point.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is increasingly viewed as a way to reduce poverty and spur economic growth among developing countries. It provides not only employment and financial capital, but also a means of transferring technology and skills, and increasing access to global markets. Yet poorer countries are relatively less successful at attracting FDI than their wealthier counterparts. This observation, coupled with the disparate health indicators between industrial and developing countries, prompted Marcella Alsan, David Bloom, and David Canning to investigate The Effect of Population Health on Foreign Direct Investment (NBER Working Paper No. 10596). The authors analyze data from 74 countries, industrial and developing, over 1980 to 2000, to determine whether health influences FDI flows. They find that good population health -- measured by average life expectancy -- has the extra merit of attracting more FDI.

Health, the authors note, is an integral component of human capital that enhances economic performance and productivity for the individual and thereby for the nation as a whole. Healthy workers are generally more physically and mentally robust than those afflicted with disease or disability. They are less likely to be absent from work because of personal or household illness. Healthier children tend to learn more easily and are less likely to be absent from school. Thus, they become better educated, higher earning adults. Healthier workers, with lower rates of absenteeism and longer life expectancies, acquire more job experience.

You can find the paper here (but it is subscription to the NBER only). This IMF paper which is feely available is also very much to the point:

Bloom, David E, David Canning, and Dean T. Jamison, Health, Wealth, and Welfare, IMF publications, Finance & Development March 2004.

Sidebar Matters I

Today I have added a link to the Economics and Biodemography of Aging and Health Care Workshop at the Centre for Population Economics, University of Chicago. They have a very interesting seminar programme, and tend to post copies of the papers presented online after the event (so if you work back down the list - including the previous page you will find some stimulating material).

Interesting up and coming sessions look to be:

David Bloom, Harvard University David Canning, Harvard University 'Demographic Change, Savings, and International Capital Flows: Theory and Evidence',

Jere Behrman, University of Pennsylvania 'Does It Pay to Become Taller? Or Is What You Know All That Really Matters?' and

Eileen Crimmins, University of Southern California 'The Role of Inflammation in Mortality Decline'.

One 'not to miss' for anyone interested in ageing and longevity is this paper from Tommy Bengtsson, University of Lund, 'The Impact of Childhood on Adult Health'.

Also new today is a section on Population Statistics. The idea for this came from a link Michael 'The Glory of Carniola' sent me on Slovenia Population Stats (Slovenia is another of those countries with heavily-below-reproduction fertility, and imminent risks of population decline). Vis-a-vis an earlier discussion on German emmigrants, Michael writes "in my experience I haven't come across any signficant populations of German workers", since our correspondent in Austria added similar qualifiers about what was actually happening in Austria and the Czech Republic my feeling is that you need to look for other - more prosperous - locations to find the German migrants. Mind you, this is becoming an important phenomenon. If you look at this page, you will see that the number of resident Germans in Germany only increased by about 23,000 between 2003and 2004, but if you look at this page, you will see that 127,000 people naturalised as Germans during 2004 (and 140,000 during 2003) so there is a big net deficit in Germans going somewhere.

Tuesday, March 21, 2006

Eastern workers yesterday and tomorrow - but never today.

The conservative-social democrat government in Berlin is voting, on 21 March 2006, to exclude workers from eight Central European countries from its labour market until 2009.

In blocking access to its labour market, the coalition led by Angela Merkel (Christian Democrat) is acting against a Commission recommendation. The EU executive has examined the labour markets of Britain and Ireland, which did not block access to workers from the east after the 2004 EU enlargement, and came to the conclusion that the two countries have profited economically from the decision.

The Merkel government, however, has already laid down in its coalition agreement that "at this time and given the developments in German labour market policy and economic policy, the extension of the transitional measures on the mobility of workers from the ten new accession countries seems to be necessary."

In fact the measures apply only to workers from the eight Central and Eastern European member states. The German coalition added that "the measures have protected the German labour market from increased migration." At the time of the conclusion of this agreement, German ministers hinted that the government might try to extend the measures until as late as 2011, the date when they will have to be lifted for the whole EU

Not the best move in the long term, nor the short. Those Eastern immigrants/workers are not going to wait until Germany decides to open its borders and on the short term they are missing out on some very motivated individuals.

Population and Development in Asia

The Asian MetaCentre is organising a three day conference from the 20 to 22 March: Population and Development in Asia, Critical Issues for a Sustainable Future.

There are two keynote speakers. Geoffrey McNicoll of the Population Council who will be speaking on "Population and Sustainability in Asia: Adjusting to a Post-Transition Era":

Large parts of Asia have completed or are nearing the end of the transition to a modern demographic regime of low death and birth rates and high median age. That does not mean that major demographic change is nearly at an end: quite the opposite. There are decades of population growth still ahead, vast relocations from countryside to cities yet to come, and continuing and rapid further shifts in age distribution toward the elderly. The supposedly calm waters of a post-transition regime, with a stationary or gently declining population, might eventually be reached, but only much later in this century. These anticipated changes, occurring alongside the region's remarkable economic transformation, add greatly to the already challenging tasks of social and environmental policymaking. The policy experience of the demographic forerunners of Europe and Japan should be examined but, given the unprecedented scale and pace of demographic change in continental Asia, may have only limited lessons to offer.

and Graeme Hugo of the University of Adelaide, speaking on "Migration and Development in Asia"

No dimension of the massive demographic, social and economic change, which has swept across Asia in the last two decades, has been more dramatic than or as far reaching in its impact as the increase in personal mobility. Population movement between and within Asian nations and to countries outside of Asia has increased greatly both in scale and diversity, and mobility is now an option for most Asians as they assess their life chances. The relationship between mobility and development, however is a complex and two way one, although the understanding of that relationship remains limited generally but particularly in the Asian region. Data relevant to investigating the relationship are in short supply and the research regarding it is patchy. The present paper seeks to assess the current state of knowledge with respect to population movement and development in the Asian region.

continue reading #

Monday, March 20, 2006

Belarus and Demography

Belarus is of course in the news this weekend. It is mainly in the news for the fact that its leader - Alexander Lukashenko - is described by the United States as Europe’s last dictator, and for the fact that despite this (or perhaps because of it) he appears to have won around 90% of the vote in yesterday's elections, amid the cries of 'foul' from a significant and ever more vocal group of internal opponents.

What isn't perhaps so well known is the demographic backdrop to all of this. Belarus's current populatlion stands at around 9.75 million. Back in November 2005, the Belarus Ministry of Statistics and Analysis reported that in the first nine months of 2005 the population had declined by 38,600. In 2004 it declined by 49,000.

Belarus began its population decline in 1994 (the peak population was 10.24 million at the end of 1993). According to the most recent UN estimates, by the year 2050 there may be only 7 million people left in Belarus, and a large proportion of those will be in the older age groups, which will not be especially old since in Belarus (as in mother Russia herself) life expectancy for men has dropped markedly in recent years, to the current level of 62.8. This is more than 13 years lower than what males in countries like Germany or France may expect, and some eight years less than in Poland. Women on the other hand have a considerably better outlook with an expected lifespan of some 74.3 years.

In general the picture is not that disimmilar from what is to be found in Russia itself (with the significant difference that there doesn't seem to be much scope for inward migration). Big killers among men are things like cardiovascular disease and alocholism (according to the Ministry of Public Health Care, there are more than 253,000 alcoholics and drug addicts in Belarus today), and of course HIV/aids is also a problem. There are some Belarus-specific issues too, like the longer term impact of Chernobyl: of those from affected zones who check their health at the Belarusian Institute of Radiation Medicine, some 60-70% are found to register excess radioactivity.

So Belarus doesn't only have a democratic deficit, it also has a demographic one. In this particular context the question is raised as to what the connection between these two might be, and what real future awaits a country with the accumulated problem set which Belarus has?

More background to Belarus's demographic disaster can be found here, and here.

Sunday, March 19, 2006

Immigration Matters

update: In the past week the news about a further decline in the birthrate created quite a discussion in the German media which took me by surprise. For some reason the critical barrier which made people take notice was births slipping under the 700.000 mark. Actually this isn´t remarkable nor shocking, at least for anyone who has followed the matter for a few years. The population projections have predicted this trend for years and it is mentioned in countless reports and papers by many institutions, demographers, analysts and researchers.

The decline in births isn´t the issue here but the fact that the population has already started to decrease (slightly), mainly due to a lower net immigration. So I´ve decided to come back to this post and emphasize why it´s the immigration that matters.

The real issue that I was trying to point out in my original post was net immigration. Since 2001 this has been steadily dropping to about 90-80.000. This is odd for a number of reasons if you start to look closer at the figures. I´ve compiled this graph at the top with immigration and emigration figures from the Statistisches Bundesamt for the period 1950-2004.

My focus is on the period after 1990. After the the fall of the Berlin wall, German immigration jumped to record levels (1,5 mil in 1992) mainly due to a influx from migrants from eastern Europe. After 1992 the number of immigrants slowly dropped. Since 1995 the numbers of immigrants continues to hover around 900-750.000 yet since 2003 the net inflow has dropped to 90-80.000. Why is this happening? Right now I can only give the first part of the answer : emigration. More and people are emigrating and if this trend continues Germany might become an emigrant country (at least for a short run before immigration picks up again). This aspect, that countries that face population decline might also see an increase in emigration is something I´ve never seen mentioned as a credible option in theory before. Yet the numbers are telling a different story.

The 2nd part is why people are emigrating: Is it due to the economic downturn? Immigrants moving on or returning home? What are the factors for this increase? I´ll be looking deeper into this in another post. In the meantime I welcome comments on this issue.

Germany´s net migration stays low.

The German Statistisches

Bundesamt has published its official population prognosis for 2005.

The German population will decline slightly from 82,5 mil to 82,45 mil in 2005. Aprox. 820-830.000 people died in 2005 , slightly up from 818.000 in 2004. The main cause in 2005 for the drop was a further decline in births, from 706.000 in 2004 down to 680-690.000 in 2005. Net migration into Germany continues to stay low with aprox. 80-90.000 people compared with 83.000 in 2004. In itself it´s curious that German net migration is so low because Eurostat reports that EU wide net migration is on the increase after a dip during the mid 1990´s.

This will be the third year in a row Germany experienced a decline. The last time Germany experienced a decline was in 1998. Back then it was also due to a large drop in net migration.

Friday, March 17, 2006

Migration In Spain

Immigration into Spain is proceeding, as we probably all know by now, at a globally unprecedented rate. Randy has a post on this here, and I have a slighly different take on it here.

Two researchers who are working on this topic are Marta Roig Vila (of the United Nations Population Division) and Teresa Castro Martín (of the Spanish Council for Scientific Research). They gave a paper at last years IUSSP conference: Immigrant mothers, Spanish babies: Longing for a baby-boom in a lowest-low fertility society.

In the paper they make a point which is relevant to my last post on the US:

The debate (about the role of immigration in a declining fertility context, EH) has mainly focused on the rejuvenating effect of sustained entries of young adults, and less attention has been paid to the contribution of immigrant fertility, despite the fact that the proportion of children from foreign-born mothers is increasing significantly.

As Roig Vila and Castro Martin suggest we have on offer two (slightly) competing views about the subsequent reproductive behaviour of recently arrived mothers - maintenance and adaptation:

The existing literature has put forward different hypotheses to explain and predict the fertility patterns of immigrants. Some authors suggest that the first generation of certain immigrant groups tend to maintain the reproductive norms and patterns of the country of origin(Abbasi-Shavazi and McDonald, 2002). A considerable number of studies support the adaptation hypothesis, which predicts that immigrants gradually adjust their reproductive behaviour to that of the host country (Andersson, 2004).

One of the problems in determining which of these effects dominate is that migrant populations are extremely heterogenous, as are their points of origin and their destinations. It may be hard to generalise here. The researchers are at some pains to stress the limited data they are working from and the potential limitations of the data they actually have, nonetheless they do seem to draw some tentative conclusions. They find the adaptation hypothesis to be more or less weakly confirmed:

"Our findings show that, net of the effect of age, marital status, parity and educational composition, the fertility gap between foreign and Spanish women narrows considerably. In fact, after controlling for these factors, only Northern African women present a higher risk of current fertility than Spaniards. This may reflect the fact that women from this region are more likely to migrate for marriage or family reunification rather than for work –as reflected in their low participation in the labour force–, the opposite that occurs with the rest of the immigration groups".

This result might seem strange in the light of my previous post on the impact of immigration on US fertility, but perhaps it is important to bear in mind that these results are net of age and net of educational composition, which are both likely, in and of themselves, to be extremely important: that is the age structure and the educational level of the migrants is what, for net fertility purposes, actually matters most. In both these cases the composition of hispanic migration into the US in recent years has been extremely propitious to increasing the overall fertility reading.

References

Abbasi-Shavazi, M. and P. McDonald (2002). A comparison of fertility patterns of European immigrants in Australia with those in the countries of origin. Genus 58(1): 53-76.

Andersson, G. (2004). Childbearing after migration: Fertility patterns of foreign-born women in Sweden. International Migration Review 38(3): 747-774.

Thursday, March 16, 2006

More On US Demographics

"Is American society really so resilient that nothing can shake its foundation?" asked Claus in the last post. Well the answer obviously is no, since no society is that resilient. But is the US pretty well insulated from the current round of demographic shocks? This might be a more interesting question. I think the answer would be probably "yes", at least up to 2020 (the same probably also goes for the UK and France which are going to encounter relatively benign ageing in the short term). As ageing expert Axel Borsch Supan never tires of saying, Germany is now where the US will only be 20 years from now.

One part of the reason for this important difference is obvious, and the explanation comes in one single, simple word: immigration. These three societies (UK, France and the US) have relatively higher fertility rates due to their previous significant immigration. Let's look at the US case.

In the first place why is US fertility so different from many of the other OECD societies? Well some explanation can be found here.

And part of the explanation for the variation in regimes across ethnic groups comes from the fact that one of the groups (the hispanic one) is composed of a large number of relatively recent migrants.

Now in order to try and understand this process my first exhibit will be a graph of US fertility across the years. As can be seen, fertility was declining steadily until the late 80s when, surprise surprise, it starts to pick up again. What a coincidence that this revival comes at exactly the time when large scale irregular migration from Latin America begins to take off!

There is a clear break in the mid-seventies. Part of the reason for this is the start of large scale inward migration, and another part is probably a steadying up in the birth postponement process which had probably been in operation for some time, and with this steadying up comes the arrival of the missing births which had been displaced, and with these an upward turn in the TFR.

My second exhibit is a graph of US population by age structure. From this it is clear that something interesting happened between 25 and 30 years ago, since there is a distinct kink in the graphs.

And the third exhibit is a graph of foreign born population who entered the US between 2000 and 2003 by age structure. From this you can clearly see the concentration of recent immigrant arrivals in the childbearing ages.

Impact of ageing in USA?

"The face of aging in the United States is changing dramatically — and rapidly, according to a new report from the U.S. Census Bureau. Today’s older Americans are very different from their predecessors, living longer, having lower rates of disability, achieving higher levels of education and less often living in poverty. And the baby boomers, the first of whom celebrated their 60th birthdays in 2006, promise to redefine further what it means to grow older in America.

“The social and economic implications of an aging population — and of the baby boom in particular — are likely to be profound for both individuals and society,” says Census Bureau Director Louis Kincannon."

Reading through the narrative of the highlighted trends the ageing population is clearly given a positive spin. The main focus is that the old people of the future will be richer, healthier, better educated and longer living than their predecessors. This is obviously a good sign but will this fact cushion the more broad societal and economic effect of an ageing population which we have pointed to in the context of other countries. Is this in fact like the US economy where dark matters make trade deficits go away and where budget deficits are justified through the venerable Arthur Laffer? Is the American society really so resilient that nothing can shake its foundation?

Admittedly, the demographic study might not have been inquisitive about the impact of ageing on the US economy at the offset, but below in the comments you now have the chance to give it a more critical spin than the one I think it is given.

Wednesday, March 15, 2006

"Denn eines ist sicher: die Rente"

So its clear that Germany is making some headway in reforms. But will it work? The German electorate might see things differently in the next election. The fact that there is a grand coalition might be a blessing in disguise. There´s no significant opposition left to vote for.

source: FAZ 22 jan 2006 "Die Rente steigt nie wieder" 31 jan 2006 "Denn eines ist sicher - die Rentenkürzung"

And The Blind Shall See!

This development seems to be incredible (hat tip to John Hawks):

"Scientists partially restored the vision in blinded hamsters by plugging gaps in their injured brains with a synthetic substance that allowed brain cells to reconnect with one another, a new study reports."

"If it can be applied to humans, the microscopic material could one day help restore sensory and motor function to patients suffering from strokes and injuries of the brain or spinal cord. It could also help mend cuts made in the brain during surgery."

"the substance contains nano-sized particles that self-assemble into a fibrous mesh. The mesh mimics the body's natural connective tissue when placed in contact with living cells.

The mesh allows existing neurons whose axons have been severed by injury or stroke to reconnect. Axons are branchlike projections that link neurons to one other, allowing them to communicate. When many axons are bundled together, they form a nerve."

The study is detailed in this week's online version of the journal for the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. I can't seem to find the link but you can find some MIT details here.

This kind of research indicates the potential that is there for leveraging advanced technologies to enhance the quality of life as well as our capacities during all those extra years that modern medical care systems seem to be making available.

BTW a small, buy one get one for free, extra. Rutledge Ellis-Behnke isn't only interested in restoring sight to the blind, he is also working on a 'hobby': the paperless classroom. In looking for his website I came across this fascinating video link about this material:

This project is the systematic replacement of paper by tablets for the students as well as the replacement of the chalkboard for the professor. We are attempting to understand the limiting factors associated with the use of this technology on a daily basis. To this end we are recording reliability, usability and the increase in learning that is derived from the use of Tablet PC’s. We are also attempting to measure the fundamental shift required to eliminate paper and to create instantaneous access to the information for the students. This will serve to increase the speed of learning.

You can find details of his talk by scrolling down this page. The video is really worth the effort. What he has done is, in effect, a piece of ethnography. The details are fascinating, especially the behavioural changes he finds between the tablet and the laptop.

Monday, March 13, 2006

Species Migrations and Extinctions

Incidentally, in case you hadn't noticed, humans aren't the only species who evolve and migrate. I am just listening to Elizabeth Kolbert talking to Open Source Radio presenter Chris Lydon about how changes in temperature and weather patterns will drive — are already driving — animals, plants, and bugs to migrate and evolve, and, be warned, sometimes to die out. You can listen to the download here.

Old Age and Human Evolution

Possibly it isn't especially noticeable, but this weekend I've been working on the sidebar. In particular I've added a new category of 'scientific blogs' whole interests one way or another touch on those we have here. Among these John Hawks Anthropology Weblog. This morning I notice that John's most recent post is indeed of interest to us:

".....mortality rates are malleable. They are changed not only by improvements in health, nutrition, and environment across the lifespan; they are also improved by short-term changes in older adults."

John is, as you might imagine from the title of his blog, probably more interested in the Upper Paleolithic than he is in our contemporary issues, but the two epochs are not entirely unconnected in what we can learn from them about the evolution of our lifespan. John's post is also useful since it serves as an introduction to the work of James Vaupel and raises importanbt issues about the relations between genetics and culture in understanding our lifespan.

In so doing he directs us to two other researchers - Sang-Hee Lee and Rachel Caspari

- whose work centres on this topic. In a recent paper Caspari and Lee conclude that:

"the increase in adult survivorship associated with the Upper Paleolithic is not a biological attribute of modern humans, but reflects important cultural adaptations promoting the demographic and material representations of modernity".

Unfortunately this paper is not freely available online, but an earlier paper - Older age becomes common late in human evolution - (published by the US National Academy of Sciences) is:

"Increased longevity, expressed as number of individuals surviving to older adulthood, represents one of the ways the human life history pattern differs from other primates. We believe it is a critical demographic factor in the development of human culture. Here, we examine when changes in longevity occurred by assessing the ratio of older to younger adults in four hominid dental samples from successive time periods, and by determining the significance of differences in these ratios. Younger and older adult status is assessed by wear seriation of each sample. Whereas there is significant increased longevity between all groups, indicating a trend of increased adult survivorship over the course of human evolution, there is a dramatic increase in longevity in the modern humans of the Early Upper Paleolithic. We believe that this great increase contributed to population expansions and cultural innovations associated with modernity."

Incidentally you can find a good selection of Sang-Hee Lee's work here.

Sunday, March 12, 2006

Ideal family Size

This is a sort of 'summary' post to introduce a fairly complex topic. Basically one part of the 'low fertility' debate centres around the idea that many women in the end have less children than they actually want. This argument is normally deployed to support the idea that developed societies are far nearer replacement fertility than they think, and that with the right kind of institutional support fertility can be teased (word used advisedly) back up again.

This is normally associated with the idea of a carrot rather than a stick variety of pro-natalism. Obviously the former is the only type which can actually hope to have any kind of success in a 'mature' society. The demographer who is perhaps most closely associated with the view that policy can work is the Australian Peter McDonald, and you can find a representative sample of his ideas here.

Now the data used to support the idea that women tend to want around two children each is normally extracted from attitude and opinion surveys. This data is hard to interpret, and of yet to be determined real validity, but let's leave this on one side for the moment. It is the best we have.

Normally in an EU context this type of information is to be found in Eurobarometer surveys, and the next one of these relating to desired fertility is due this summer (June I think). Meantime the Austrian demographer Wolfgang Lutz has drawn attention to the fact that desired family size was already found to be falling in some countries in the last Eurobarometer survey (2001), and in particular in some countries (Germany and Austria) where fertility has already been at below replacement levels for a generation or so. The German-speaking regions seemed at this stage to have formed some sort of cluster of low fertility ideals, since ideal family size averaged 1.6 in the former East Germany, and about 1.7 in both Austria and the former West Germany. Lutz has written many times on this topic, but the most interesting paper is perhaps this one: The Emergence of Sub-Replacement Family Size Ideals in Europe (written with Joshua Goldstein and Rosa Maria Testa). I reproduce below the conclusions of this paper:

In the larger debate about below-replacement fertility, childbearing intentions have been largely ignored because they have seemed to be such an unresponsive indicator of changing behaviour. Now, for the first time, we see that fertility ideals really do seem to be changing. Demographers have placed great emphasis on the importance of tempo effects, delayed childbearing, in producing low period fertility rates. The survey results we present here, however, indicate a deeper and more durable societal change, a decline in family size ideals.

What does this imply about future fertility? First of all, it would suggest to us that we should not be surprised if fertility declines further in Germany – or fails to increase, as Bongaarts and others have argued. Expected fertility averages 1.5 children per women among the younger cohorts in Austria and Germany. It would not surprise us if cohort fertility does not surpass these levels. Second, low family size-ideals may create a momentum of their own making it more difficult for pro-natalist policy makers to raise fertility levels in the future. Finally, if the generational lag in fertility preferences is correct, this would imply that we will see falling family size ideals in other low-fertility countries, like Italy and Spain, in the decade or so ahead.

The below-replacement ideals prevalent among young Austrians and Germans may or may not be a sign of the future in low-fertility populations. But it is notable that for the first time people’s stated preferences have deviated from the two-child ideal that has held such sway since the end of the baby boom. It is hard to imagine that this reconceptualization of family life will be without any consequences, just as it is hard to imagine that low fertility can persist indefinitely without being accompanied by a change in ideals.

More recently the EU funded DIALOG project collected data from 30,000 people in 14 European countries on their attitudes and opinions concerning family numbers, fertility behaviour and demographic change. The study found that in the main the two child 'ideal' was still common across Europe, but noted that below replacement ideals now existed in Germany, Italy, Austria and Belgium and the Czech Republic (The desired number of children per women in Germany was found to be (1,75), in Italy (1,92), in Austria (1,84), in the Czech republic (1,97) and... in Belgium(1,86)).

The results of this summers Eurobarometer now eagerly awaited.

Saturday, March 11, 2006

Neo-Classical Growth?

Is there, or isn't there an ageing impact on our economies? Well one way of addressing this issue is to look at the recent economic performance of some of those who are most directly affected. Now one of the key postulates of neo-classical growth theory is that each economy has its own long run steady state growth rate. This is in many ways a highly questionable assumption and is one which, with the notable exception of the US, is very hard to sustain empirically over the longer term. Economic performance tends to fluctuate, the big question is: does it fluctuate following any kind of identifiable pattern?

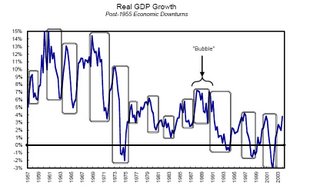

Well, lets take a look at the Japanese case. Here's a convenient graph of Japanese economic growth 1955 to 2003 prepared by US economist Michael Smitka from Japanese data available here.

What is obvious from looking at this profile is that Japanese growth has been far from uniform over the last 50 years or so. This really shouldn't be so surprising when we think about economic theory a little. Key components of economic growth are the proportions of the total population working, and the kinds of activities they are engaged in. Now if we look at the early part of the graph we can see very high growth rates (which we can also find in eg China now). These are due in part to an ever greater part of the total population becoming involved in economically productive activity, and to a technological 'catching up' process. As developing countries tend to start at some distance from the existing technological frontier then growth can be proportionately more rapid as they close the distance (again this can be seen now in the Eastern European EU accession economies).

With time this growth spurt eventually slows, but the loss is to some extent offset as a society moves up the median age brackets by a growing importance of what have come to be known as 'prime age workers'. The prime age wage/productivity effect can be seen in the chart below which shows how the age related earnings structure has altered in Japan over the years between 1970 and 1997.

The most important point to note is that wages generally peak somewhere in the 50-54 range (even though many workers in Japan currently continue to work to 75) and this wage profile may be assumed to be some sort of proxy for what actually happens to productivity. One very revealing detail is that while the shape of the hump has changed somewhat over the years there has been little noticeable drift to the right, which should give some indication of the age-related productivity problem.

Going back to the upper chart, post-bubble Japan has grown significantly more slowly, although thanks to the strong export position (and China related demand) the economy has still managed an average of 2.5% a year since the end of 2001.

The same cannot be said of Italy, which due to its much weaker product profile cannot expect the export vibrance that a Germany or a Japan can attain, but as can be seen from the accompanying graph, trend growth in Italy has been steadily declining since the end of the 1960s:

Indeed since 1990 Italian GDP growth has only managed an average of something like 1.4% growth per annum, as can be seen is the next chart.

As the Economist (from whom the accompanying chart is drawn) points out Italy's average economic growth over the past 15 years has been the slowest in the European Union, and all the years of low growth take a toll, since it's economy is now only about 80% the size of the UK one.

As the Economist (from whom the accompanying chart is drawn) points out Italy's average economic growth over the past 15 years has been the slowest in the European Union, and all the years of low growth take a toll, since it's economy is now only about 80% the size of the UK one.The German case, whilst it is significantly better than the Italian one, still shows some similar characteristics. According to the Federal Statistics Office:

Measured in terms of gross domestic product changes at 1995 prices, the rates of economic growth in the former territory of the Federal Republic of Germany and - since 1991 - in Germany have continuously declined since 1970. While the average annual change was 2.8% between 1970 and 1980, it amounted to 2.6% between 1980 and 1991 and to 1.5% between 1991 and 2001.

Recent years have been worse rather than better, and the German economy shrank (0.2%) in 2003, and grew by 1.1% in both 2004 and 2005.

So there we have it. Japan, Germany and Italy are the three oldest societies on the planet (median ages 42.64,42.16 and 41.77 respectively), and the economic growth record seems to bear out the suggestion that ageing does have a noteable impact on economic performance.

Friday, March 10, 2006

So, you think you can fix the demographic crisis, right?

Using the data in the rather interesting Table 6 of the EC's paper The economic impact of ageing populations in the EU25 Member States we linked to, let's do a quick back of the envelope calculation about what we could do to help Italy get to 2050 in a good economic shape. After all, I'll be about seventy by then; I might want to retire to Firenze like Hannibal Lecter ("retire" of course, will be relative by then).

The concrete problem is this: The EC projection indicates a 1.5% average annual GDP per capita growth for Italy in the period 2004-2050. How hard would it be to raise it to 2%? Two percent isn't an unreasonable figure, is it? But the demographic shift makes it quite challenging.

Basically, you need to change the average annual change in labor input from -0.2 to 0.3 points. As the former figure takes account of changes in participation, postponed retirement, etc, this can only come from a combination of migration, unexpected extra delays to retirement (which can only come from unexpected extension of life, as all the slack is already accounted for in the table), or changing demographic dynamics.

For the latter, as children per woman in Italy are about 1.23, you'd need to raise that to (handwaving) about twice that. *Or* you can take immigrants, but the economically active population of Italy is about 25 million (right now), so we are talking in the order of more than a thousand qualified migrants a _year_. For ever and ever (of course, pretty soon they'll start changing the aggregate dynamics themselves, so perhaps you'll get off lightly - but there's still the fact that few

countries attract that number of migrants, and even fewer are integrating them well).

*Or* you can raise life expectancy enough so 0.3% of your population that would leave the productive age bracket would stay there. Now, assuming a bit of linearity here and there (retirement, after all, will be already as close to death as possible), as Italy's death rate is about 1.0% each year, this would mean, roughly, that you have to prevent one in three deaths that would happen each year. Just to put this in perspective: that's equivalent to curing cancer.

These are your choices, then (without being too serious about it):

* Convince every woman in Italy to have twice as many children as she had planned to have.

* Import a hundred thousand working-age migrants (with the average productivity of the average Italian) per year.

* Cure cancer.

Bottom line: There'll be no easy solutions, probably no reasonable ones, and certainly no "normal" ones. This problem will take some creativity to solve.

An Ageing Problem?

In a comment on CAP TvK's Ageing in the EU 25 post David Friedman said:

"Progress in biological knowledge has been very rapid in the past century, so it wouldn't be surprising if, well before 2050, the aging problem was solved."

Here there are two issues: that improvements in biological knowledge can lead to longer, more productive lives, and that ageing is a problem, and indeed a problem that has a solution. This post will adress the latter issue.

Ageing is a term we often use and hear today, but what do we really mean by it?

This commonplace that we are ageing is I suppose both self-evident - individually we are always that little bit older, each and every day - and surprising - Niger is getting older, Mali is getting older, Somalia is getting older. This is surprising since these are, effectively, among the youngest societies on earth (Niger, median age 15.8, Mali, median age 16.35, Somalia, median age 17.59). Now everyone is aware that Japan is getting older, everyone is aware that Germany is getting older (these are currently the two oldest societies on the planet), but Niger, Mali and Somalia!

In fact, apart from 18 'demographic outliers' as identified in the 2005 United Nations Human Development Report, each and every country on the planet is getting older. (For a comprehensive list of median ages go here). Nor is this societal 'ageing' a recent phenomenon, it starts from virually the outset of what has become known as the demographic transition - a process which began in many European societies in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. This transition begins with a sudden and sustained drop in mortality, especially in infant mortality, and as a result of this mortality decline a society becomes 'suddenly young', since the child and youth cohorts rapidly become large in comparison with older age groups. The point most commentators seem to have missed here is that after this it is continuous ageing all the way, and forever. There is no end point in this sense. Nor should the fact that median ages are rising be seen as in and of itself a problem. It is, in fact, part of the normal pattern of events in an industrial and post industrial age.

Global life expectancy, to take but one example, has more than doubled over the past two hundred years, climbing from an estimated 25 years in 1800, to the present level of 65 for men and 70 for women. During this whole period maximum life expectancy has risen steadily by more than two years a decade

So if this weblog is, in part, about ageing, its starting point should be that this ageing is not a new or recent phenomenon (the 'discovery of ageing' is of course more recent, but that is another story) or even a phenomenon which we should view with particular preoccupation.

In conclusion back for a moment to the end point? This is the really interesting part, there is no end point, as life expectancy continues to push ever onwards and upwards we will all be living longer, and to date there does not seem to be any special biological limit to this process. Some may even live to see the day when Keynes's dictum "in the long run we are all dead" may even no longer hold. That is the good news.

P.S. This post has been basically ripped off from a couple of paragraphs in the introduction to a much longer work. I simply think the point needs making.

Thursday, March 09, 2006

Ageing in the EU25: a short introduction.

The 2nd part goes into the projections for all the EU-25 members. It also gives three distinct time periods the EU zone will go through.

"• 2004-2011 – window of opportunity when both demographic and employment developments are supportive of growth: both the working-age population and the number of persons employed increase during this period. However, the rate of increase slow down, indicating that the effect of an ageing population is starting to take hold even if it is not yet visible in aggregate terms. This period can be viewed as a window of opportunity, since both demographics and labour force trends are supportive of growth. Conditions for pursuing structural reforms may consequently be relatively more favourable than in subsequent years "

"• 2012-2017 – rising employment rates offset the decline in the working-age population:

during this period, the working-age population will start to decline as the baby-boom generation enter retirement. However, the continued projected increase in the employment rates of women and older workers will cushion the demographic factors and the overall number of people employed will continue to increase, albeit at a slower pace. From 2012 onwards, the tightening labour market conditions (lower labour force growth together with unemployment down to NAIRU) may increase the risk of labour market mismatch "

"• the ageing effect dominates from 2018: the trend increase in female employment rates will broadly have worked itself through by 2017, with only a very slow additional increase projected in the period 2018-2050. In the absence of further pension reforms, the employment rate of older workers is also projected to reach a steady state. Consequently, there is no counter-balancing factor to ageing, and thus both the size of the working-age population and the number of people employed are on a downward trajectory. Having increased by some 20 million between 2004 and 2017, employment during this last phase is projected to contract by almost 30 million, i.e. a fall of nearly 10 million over the entire projection period of 2004 to 2050."

The New Generations of Europeans

In The Name Of Science

Well as many of us well know, science isn't always all it's cracked up to be, or all it should be. Following the recent and much publicised issue of stem cell research claims made by Korean scientist Woo Suk Hwang (incidentally, they really do seem to have cloned a dog), today Nature is running the story of another dubious case. This time it is the claim of Purdue nuclear engineer Rusi Taleyarkhan's claims to have achieved table-top fusion in collapsing bubbles back in 2002 which are being put under the magnifying glass (and here). Whatever the final conclusion which is drawn in both these cases, two points should not escape our attention.

Firstly, the vast majority of practising scientists carry out high quality work free from any contamination with the types of issues raised in these cases. Secondly, that the large quantities of resources and institutional support now involved in carrying out research mean that science has, despite all the undoubted excellence, now moved along way from the conceptions we once had of it. In a cerain sense some kind of recall to order is long overdue. But what kind of order? Well in recent days, in trying to explain to others the objects and ambitions of this weblog I have often found myself saying, "you know, a scientific blog, in the Mertonian sense". The what, has normally been the response. How deep our vision, but how shallow our memory I often find myself thinking.

The Merton in question - Robert K Merton - was once upon a time the best known US disciple of the functionalist sociologist Talcott Parsons, and among other things he was an able and interesting theorist of the sociology of science. Merton is probably best remembered for what have subsequently become known as the Mertonian Norms, or simply by their acronym CUDOS. Cudos stands for

- Communalism

- Universalism

- Disinterestedness

- Originality

- Skepticism

Altruism Rules

Interesting piece of news this one:

Infants as young as 18 months show altruistic behaviour, suggesting humans have a natural tendency to be helpful, German researchers have discovered.

Infants as young as 18 months show altruistic behaviour, suggesting humans have a natural tendency to be helpful, German researchers have discovered.In experiments reported in the journal Science, toddlers helped strangers complete tasks such as stacking books. Young chimps did the same, providing the first evidence of altruism in non human primates.

As a fully paid up member of the Bonobo fanclub I can only say I welcome the news that both humans and chimps have 'bonobo-like' qualities, qualities I hasten to add which now seem to have been favoured by adaptive evolution. There is useful coverage in Scientific American:

Alicia Melis of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, and her colleagues presented chimpanzees at a sanctuary in Uganda with a cooperative challenge. To reach a food tray from behind bars, a chimpanzee had to pull on two ends of a rope threaded through metal loops on the tray. If the chimpanzee simply pulled on one end, the rope would slip the loop. If, however, the chimpanzee unlocked the door to an adjacent room, released a fellow chimp, and cooperated with it to pull on both ends of the rope at the same time, both would be rewarded with the food on the tray..

Here,s an interesting paper from Tomasello: Understanding and sharing intentions: The origins of cultural cognition, and here's the research project home page, and here's a link to Joan Silk's webpage, Silk also works with Chimpanzees.

Also, don't miss these two simple videos comparing human and chimp resonse times to someone in need.

"I think it's extremely interesting that these very young children are behaving in a helpful way," says University of California, Los Angeles, biological anthropologist Joan Silk, who led the food-lever study. "It suggests that just like infants are wired up to imitate, they're wired up to help." As for the chimps, the new experiments suggest that they may have a more altruistic nature than the food experiments suggested, Silk says. "It may be that when chimps see food, they can only think of themselves." An alternative explanation, she says, is that chimps may be more likely to help a human caretaker than one of their own."

"I think it's extremely interesting that these very young children are behaving in a helpful way," says University of California, Los Angeles, biological anthropologist Joan Silk, who led the food-lever study. "It suggests that just like infants are wired up to imitate, they're wired up to help." As for the chimps, the new experiments suggest that they may have a more altruistic nature than the food experiments suggested, Silk says. "It may be that when chimps see food, they can only think of themselves." An alternative explanation, she says, is that chimps may be more likely to help a human caretaker than one of their own."

Wednesday, March 08, 2006

Demographip trends show us the real emerging economies

(the whole article is pasted below)

"Changes in the makeup of Russia's population are set take a heavy toll on the economy, according to a PricewaterhouseCoopers report released Monday.

"The impact of a declining, aging population is particularly significant in restricting Russia's ability to increase its share of world GDP in a similar way to other large emerging economies," the report said.

The consultancy projected that the combined gross domestic product of the so-called E7 group of leading emerging economies -- China, India, Brazil, Russia, Indonesia, Mexico and Turkey -- will become 25 percent larger than that of the Group of Seven industrialized heavyweights by 2050. The G7 includes the United States, Japan, Germany, Britain, France, Italy and Canada.

Russia's rapidly declining working-age population will cause its economy to grow at a significantly slower rate than that of its peers, according to PwC. India and Indonesia are in a better position than Russia, PwC said, because they are currently experiencing a small boom in their labor forces.

Russia, which is expected to undergo the worst demographic crisis among the E7 countries, is not expected to approach the size of France's economy until 2050, PwC said."

Essentially you don't have to go into the report, but I still think the conclusions are worth scrutinizing.

"(...) there are likely to be notable shifts in relative growth rates within the E7, driven by divergent demographic trends. In particular, both China and Russia are expected to experience significant declines in their working age populations between 2005 and 2050, in contrast to relatively younger countries such as India, Indonesia, Brazil, Turkey and Mexico, whose working age populations should on average show positive growth over this period, although they too will have begun to see the effects of ageing by the middle of the century."

Even at a short glance the report looks to be solid so I can highly recommend to read the charts and conclusions.

Immigration Matters Too

There is quite a lot of info on immigration in the news today. First off the starting block is the fact that the number of illegal immigrants inside the US has continued to grow by nearly half a million a year over the last 5 years according to a survey released yesterday by the Pew Hispanic Centre. This is quite a large number, but to put it (or the Spanish construction boom if you prefer) into perspective, irregular migration into Spain has been running at over 600,000 a year over the same period. So for a country the size of the United States this should make you raise an eyebrow, but it shouldn't cause you to fall off your seat (the Spanish case though perhaps should).

To put this (and perhaps the US housing boom) in even greater perspective this earlier report points out that :

"The number of migrants coming to the United States each year, legally and illegally, grew very rapidly starting in the mid-1990s, hit a peak at the end of the decade, and then declined substantially after 2001. By 2004, the annual inflow of foreign-born persons was down 24% from its all-time high in 2000"

Meantime the UK is struggling hard to regularise its migratory flows and the Home Office has announced the creation of an immigration points system that would give preference to young highly skilled professionals and entrepreneurs and make it more difficult for low skilled workers to fill jobs. Lower skilled 'third tier' workers - such as agricultural workers, hotel and catering staff - the demand for whom seems to be in reality what fuels the flows, would only be allowed in if “specific temporary labour shortages” can be identified by a newly proposed independent Skills Advisory Body.

Of course, generally there are mixed opinions about the economic plusses and minuses of migration. Some level of immigration is almost certainly necessary, especially in those cases where we are successful in ensuring that our own young people move up the value chain in terms of the kinds of occupations they can realistically aspire to. Also those countries with very low fertility most definitely are in need of some systematic immigration.

However we are now a long way on in the debate from the early UN proposal for replacement migration as a catch all solution to long term structural demographic changes. As I noted in this post, David Coleman has not been backward in coming forward to point out some of the problems large scale migration poses, while Nigel Harris seems to occupy the opposing corner.

Wolfgang Lutz has another attempt to address the issue in a paper with Sergei Scherbov - Can Immigration Compensate for Europe’s Low Fertility, and Kotlikoff, Fehr and Jokisch add their two cents worth in The Developed World’s Demographic Transition – The Roles of Capital Flows, Immigration, and Policy.

At the end of the day, as well as facilitating some immigration I cannot help but feel we need to give some more serious and urgent consideration to the question of raising participation rates in the higher age groups, and at the same time to systematically revising upwards our anticipated retirement ages.

Tuesday, March 07, 2006

Middle Aged and Stranded

Well, I suppose that is one step better than being busted-flat and legless (or even like Bonnie Tyler: lost in France) ! But seriously folks sociologist Richard Sennett has an article in todays FT (and here in case of link rot) which is relevant to points being made by Marcelo in this post.

Sennett and his German counterpart Ulrich Beck are what you might call 'risk contrarians', they don't seem to like it, but more importantly they don't seem to understand what lies behind the perceived extra risk. Or rather, perhaps they think they do (globalisation), but then the problem starts precisely here, since isn't saying "hey things are getting more uncertain since we have faster technical change and increasingly global markets", a bit like saying "hey I'm getting wet coz it just started raining".

"..... stagnation has become intertwined with insecurity. Work has taken on a new character in recent decades for people in the middle; its risks are especially evident among those whose fortunes are tied to the “new economy” – cutting-edge, global businesses such as financial services, media and high-tech. They account for no more than 20 per cent of US and 15 per cent of British employment but in them, modern capitalism has concentrated its energies and defined its ideals."

"The new economy has reformulated workers’ experience of time. Long service and accumulated experience do not earn the rewards that more traditional companies once provided. Instead, cutting-edge businesses want young employees who can work long hours; the “youth premium” works against older employees with multiple responsibilities. Dynamic companies have also shortened the time-frame of work itself; jobs are defined as short-lived projects rather than permanent functions. In media, mid-level employees can expect increasingly to work on six or even three-month contracts, if there are contracts at all. Throughout the “new economy”, companies are rapidly changing business focus and identity in response to shifting global market conditions."

Now don't get me wrong. It's not that I'm unsymathetic to the problems that many people are facing. What I don't get is how anyone thinks you are going to turn the clock back, or why anyone in India or China or Brazil would think that you should. If Marcelo's central argument worked, it should be this middle income , well educated group who should be most amenable to using high-tech plug-ins, but if you read Sennett carefully you'll see that this is precisely one group which won't be amongst the early adopters. Rather than go down the road which Marcelo is advocating (and rightly so on my view) the most effected seem to be putting in more hours rather than 'enhancing' the hours they already spend:

Many discussions of “work-life balance” focus on the lengthening time employees now spend on the job; in Britain, the European champion, working and commuting is edging up to 11 hours daily. The people we interviewed have found various effective ways to deal with these family-time deficits; they encounter more trouble managing the unreliability of work as a source of family support. That both men and women worry about failing their families was a key finding – this spectre once haunted manual labourers but has now migrated to the middle-class. Manual labourers had strong unions to turn to; white-collar unions are weak or non-existent in the new economy.