Wednesday, December 19, 2012

On Tokyo's relative ascent in a shrinking Japan

Tuesday night is usually anime night for me and my friends, an evening when we watch some of the high-quality animated series that have made it out of Japan into North American audiences. A trope I've noticed appear frequently in anime is that of the vast city, of immense urban sprawl that dominates life. Taking a look at the statistics, Japan certainly is a highly urbanized society, not only in the simple terms of Japan being a country where more than 90% of the population lives in cities but in the reality that the Greater Tokyo Area--the conurbation dominated by Tokyo but including all seven prefectures of the Kantō region and Yamanashi Prefecture to the west--is still by many measurements the largest conurbation in the world.

Recently, Wendell Cox at his New Geography site has been producing interesting posts about, among other things, the future of Tokyo.. In September, Cox linked to a prediction of significant aging and population shrinkage in Tokyo over the 21st century.

2100 will see Tokyo's population standing at around 7.13 million — about half of what it is today — with 45.9 percent of those in the metropolis aged 65 or over, a group of academics and bureaucrats has concluded.

Tokyo's population, which stood at 13.16 million in 2010, will peak at 13.35 million in 2020 before dropping by 45.8 percent from the 2010 census figure 88 years from now, the group, including seven academics and 10 metro government and municipal bureaucrats, said Sunday.

This means the 2100 population will be resemble that of 1940's Japan, before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

"The number of people in their most productive years will decline, while local governments will face severe financial strains," the group said in a statement. "So it will be crucial to take measures to turn around the falling birthrate and enhance social security measures for the elderly."

The number of Tokyoites 65 or over, estimated at 2.68 million in 2010, will peak at 4.41 million in 2050 before falling to 3.27 million in 2100, while their presence in the overall population will rise to 37.6 percent in 2050 and 45.9 percent in 2100 compared with 20.4 percent in 2010.

Those aged in their productive years between 15 and 64 will represent 46.5 percent of the population in 2100, the group said.

The projections assume that people moving to Tokyo continue to outnumber those moving out and that the fertility rate — the average number of children a woman gives birth to over her lifetime — will remain unchanged at its 2010 level of 1.12 among Tokyo women, the lowest in the nation.

This prediction, long-range though it might be, doesn't strike me as entirely unlikely, on account of the longevity of the Japanese population, sustained low fertility rates, and low rates of immigration. (Comparing Tokyo with Seoul is salutary.) Tokyo was plausibly selected by the Still City interdisciplinary study group as the paradigmatic post-growth city, stagnant demographically, economically, and politically.

That said, as noted by Cox in June in his survey of Tokyo's demographics, Tokyo's demographics are actually substantially healthier than those of the remainder of Japan on account of Tokyo's attractiveness to migrants from elsewhere in Japan, to the point that Tokyo's relative demographic weight is only going to grow.

Japan has been centralizing for decades, principally as rural citizens have moved to the largest metropolitan areas. Since 1950, Tokyo has routinely attracted much more than its proportionate share of population growth. In the last two census periods, all Japan’s growth has been in the Tokyo metropolitan area as national population growth has stagnated. Between 2000 and 2005, the Tokyo region added 1.1 million new residents, while the rest of the nation lost 200,000 residents. The imbalance became even starker between 2005 and 2010, as Tokyo added 1.1 million new residents, while the rest of the nation lost 900,000.

Eventually, Japan’s imploding population will finally impact Tokyo. Population projections indicate that between 2010 and 2035, Tokyo will start losing population. But Tokyo's loss, at 2.1 million, would be a small fraction of the 16.5 million loss projected for the rest of the nation (Figure 5). If that occurs, Tokyo will account for 30 percent of Japan's population, compared to 16 percent in 1950. With Japan's rock-bottom fertility rate, a declining Tokyo will dominate an even larger share of the country’s declining population and economy in the coming decades.

In the post "Japan’s 2010 Census: Moving to Tokyo", Cox noted that the Greater Tokyo Area's growth is exceptional, that even the Keihanshin conurbation anchored by Osaka, Kobe, and Kyoto is declining. The decline of the only urban area comparable in size to the Greater Tokyo Area leaves the country's urban hierarchy all the more focused on the national capital.

The fortunes of the prefectures in Japan's two largest urban areas could hardly be more different. The four prefectures of the Tokyo – Yokohama area had added approximately 3,000,000 people in each five-year period until 1975. Since that time, growth has been slower, but the area has added 1 million or more people each five years from 1975 to 2010. On the other hand, the Osaka – Kobe – Kyoto area (Osaka, Hyogo, Kyoto and Nara prefectures), which also experienced strong growth after World War II, adding between one and two million people in each five year period until 1975, has seen its growth come to a virtual standstill. Over the past five years, Osaka – Kobe – Kyoto added only 12,000 people. As a result, Osaka – Kobe – Kyoto is easily the slowest growing mega-city in the world, by far. Osaka – Kobe – Kyoto seems destined to fall substantially in world urban area rankings in the years to come. Tokyo – Yokohama, however, remains at least 14 million larger than any other urban area in the world, a margin that seems likely to be secure for decades to come.

[. . .] These numbers suggest there is ample reason to worry about the concentration of population and power in the Tokyo – Yokohama area, which now contains nearly 30 percent of the nation's population. None of the world's largest nations, outside of Korea (which ranks 25th in population), are so concentrated in one urban area. Among other nations with more than 100 million the greatest concentration is in Mexico, where Mexico City accounts for less than 20 percent of the population. The largest urban areas in Brazil (Sao Paulo) and Russia (Moscow) have little more than 10 percent of the population. The largest urban area in the United States, New York, accounts for less than seven percent of the population, while in China (Shanghai) and India (Delhi), the largest urban areas house less than two percent of the population. Paris, the beneficiary of centuries of centralization, has less than 20 percent of the population.

(This sort of super-centralization isn't unique--as I noted in November 2010, half the population of South Korea lives in greater Seoul.)

What might this mean for Japan? I'd question whether there's any particular sense in Japan trying to reverse the centralization of its population in Tokyo, actually. Where will it get the funds necessary to subsidize outlying areas, like the Tohoku I surveyed back in March 2011, which has been experiencing first relative then absolute decline for generations? Seeking Alpha's observation that Japan's new trade deficit and shrinking savings leaves the country short on cash is quite valid. Can Japan afford to prop up its peripheries if the people living in these peripheries no longer want to live there?

Wednesday, November 14, 2012

On the Albertan advantage over the United States

Back in 2006 and 2007 I blogged about how the demographics of the Canadian province of Alberta were being altered by that province's substantial oil-driven prosperity, attracting migrants from across Canada. Ricardo Lopez' Los Angeles Times article "Canada looks to lure energy workers from the U.S." is the first article I've seen talking about Americans being attracted to Alberta.

With a daughter to feed, no job and $200 in the bank, Detroit pipe fitter Scott Zarembski boarded a plane on a one-way ticket to this industrial capital city.

He'd heard there was work in western Canada. Turns out he'd heard right. Within days he was wearing a hard hat at a Shell oil refinery 15 miles away in Fort Saskatchewan. Within six months he had earned almost $50,000. That was 2009. And he's still there.

"If you want to work, you can work," said Zarembski, 45. "And it's just getting started."

U.S. workers, Canada wants you.

Here in the western province of Alberta, energy companies are racing to tap the region's vast deposits of oil sands. Canada is looking to double production by the end of the decade. To do so it will have to lure more workers — tens of thousands of them — to this cold and sparsely populated place. The weak U.S. recovery is giving them a big assist.

Canadian employers are swarming U.S. job fairs, advertising on radio and YouTube and using headhunters to lure out-of-work Americans north. California, with its 10.2% unemployment rate, has become a prime target. Canadian recruiters are headed to a job fair in the Coachella Valley next month to woo construction workers idled by the housing meltdown.

The Great White North might seem a tough sell with winter coming on. But the Canadians have honed their sales pitch: free universal healthcare, good pay, quality schools, retention bonuses and steady work.

"California has a lot of workers and we hope they come up," said Mike Wo, executive director of the Edmonton Economic Development Corp.

The U.S. isn't the only place Canada is looking for labor. In Alberta, which is expecting a shortage of 114,000 skilled workers by 2021, provincial officials have been courting English-speaking tradespeople from Ireland, Scotland and other European nations. Immigrants from the Philippines, India and Africa have found work in services. But some employers prefer Americans because they adapt quickly, come from a similar culture and can visit their homes more easily.

The Canadian-American border is porous, and throughout its history has not been much of a barrier to migration whether we're talking of Americans moving north or Canadians moving south. If traditionally the flow south to the United States has been greater than the flow north into Canada, that relates to the tendency for the United States to be a more attractive destination for migrants, offering higher wages and whatnot, than Canada. (In a historical coincidence, Alberta and its neighbouring province of Saskatchewan once saw substantial American immigration, a consequence of the agricultural districts of those two provinces being opened up to colonization at the end of the 19th century as adjacent districts of the United States were finishing up the process.)

Alberta's ongoing labour shortages are a matter of public record.

Alberta has the highest job vacancy rate in the country, according to the Canadian Federation of Independent Business, and that is translating into close to 55,000 unfilled private sector jobs.

The CFIB said Tuesday that as Canada’s labour markets continue to recover from the 2008-2009 recession, the percentage of unfilled private sector jobs increased slightly from 2.3 per cent in the second quarter to 2.4 per cent in the July-to-September period.

The latest 2.4 per cent vacancy rate is equivalent to about 275,900 full- and part-time private sector jobs, said the CFIB. Canada’s construction industry has the country’s highest sectoral vacancy rate (3.7 per cent), although hospitality (2.9), agriculture, forestry and fishing (2.8), oil, gas and mining (2.8) and professional services (2.7) are also high.

Alberta and Saskatchewan have the highest vacancy rates (3.6 per cent each), while Newfoundland and Labrador (2.8) is also above the national average. Quebec (2.4), Prince Edward Island (2.2), Ontario (2.1), Manitoba (2.1), British Columbia (2.1), Nova Scotia (1.9) and New Brunswick (1.8) either match, or fall short of the overall rate.

“The smallest firms have the highest job vacancy rate and are being hit the hardest by labour and skills shortages,” said Richard Truscott, Alberta Director for CFIB. “The considerably higher rate in Alberta also clearly refutes the assertion by some labour leaders that there isn’t a shortage of qualified labour in our province.”

[. . .]

Ben Brunnen, chief economist with the Calgary Chamber of Commerce, said the vacancy numbers are consistent with the strong economic growth the province is experiencing.

“If the global economy remains stable, labour shortages are going to be the single greatest impediment to economic growth confronting Alberta. These vacancy numbers demonstrate that,” said Brunnen.

“It’s very possible that we’re right at a peak level of vacancy rates for the province … The global economy is at its highest risk of going into a recession since four years and we’ve seen some of the investment numbers for Alberta stabilize a little bit. However, we also are seeing the greatest period of net interprovincial migration since 2006. So that means people are coming to fill the job vacancies. We might see a bit of a plateau in terms of the total jobs created right now. So hopefully we’ll see a bit of an alleviation in the next few months of the labour shortage in Alberta.”

But if the global economy remains relatively stable and the United States economic picture is strong, the labour challenge could persist for Alberta employers, added Brunnen.

What's interesting to me is the extent to which these shortages are attracting substantial numbers of American migrants, a product of strength in Alberta and weakness in the United States. It'll be interesting to see where this goes in the long run, since as Brunnen notes the direction of the American labour market matters substantially.

(I'm also curious about American reactions to emigration as an idea, not least in the context of American exceptionalism and the sense that, generally, the United States is one of those countries that people travel to in order to find their fortunes, not the other way around. How is this limited change being received?)

Labels:

alberta,

canada,

emigration,

labour market,

migration,

united states

On two ways Irish workers coming to Canada can find jobs

Reading the previous month's issue of Toronto Life, I was interested to come across Robert Hough's "The Celtic Invasion: why the arrival of hundreds of Irish construction workers benefits Toronto’s building boom". The main people Hough uses to illustrate the post-boom migration to Toronto are James and Sean McQuillan, brothers in their mid-20s from Dublin whose jobs as construction workers came to an end with the boom. For them, Canada was an appealing option.

What I particularly liked in Hough's article was an extended passage examining how the McQuillans, coming to Canada, came to find jobs. There's a very long history of Irish immigration to Canada, of course, and any number of networks imaginable. Two networks, though, stand out. One of these is Gaelic football, a sport that I described in January 2011 post as being hit hard by the emigration of its players--perhaps the game is itself channeling and encouraging migration. The other? Authentic Irish pubs.

Toronto has long been an Irish city. When the potato blight ravaged Irish farmland in the late 1840s, 38,000 Irish arrived in Toronto, which at the time had a population of only 20,000. While the majority of these immigrants either moved on or died from illnesses picked up on the unenviable journey over, about 2,000 stayed, making an Irish city all the more so. The Belfast of the North, as Toronto became known for many years, earned a reputation as a good place to settle, particularly when the Canadian economy was flourishing and the Irish economy was not. This happened again around the turn of the 20th century, and there was another wave of immigration in the 1950s, when Ireland became mired in a tenacious postwar recession. A large number came from Northern Ireland during the Troubles of the 1970s, and there was another surge when Ireland’s economy stalled in the 1980s.

For Irish arriving in Toronto today, there are two tried-and-true ways to find work. The first is by playing Gaelic football, a uniquely Irish game that, at least to the uninitiated, looks like soccer, North American football and rugby all rolled into one. Thanks to the most recent exodus of unemployed Irish, participation in Gaelic football has become a global phenomenon; there are now 10 Gaelic Athletic Association squads in the GTA alone (seven male and three female), and GAA teams have popped up in such unlikely locales as Dubai, Buenos Aires, Berlin, Beijing and Shanghai. “We exist as a welcome mat for new Irish arrivals,” says Mark O’Brien, an ex-president of the Toronto area GAA. “By playing football, they can meet people, make contacts and find work. The Irish, you know, are famous for helping each other out. It’s important to us, ’cause we were all helped by the older fellas when we came over.”

There’s one catch: to benefit from the GAA’s network of contacts, you have to be a decent player. Though Caolan Quinn plays with a Toronto GAA team called St. Vincent’s, the McQuillans do not: growing up, they preferred soccer. So the brothers resorted to the other ironclad method of procuring employment in Toronto: they went to the pubs.

Though there are probably 100 Irish-style pubs in Toronto, most of them are owned by corporations, frequented by non-Irish and operated by publicans without useful insight into the happenings back home. But there are a handful of real Irish pubs. There’s McVeigh’s at Church and Richmond, which, among the older Irish, is always referred to as the Windsor House, the name it had 25 years ago. There’s McCarthy’s, a hole in the wall on Upper Gerrard near Woodbine. And there’s the Galway Arms on the Queensway in Etobicoke; the Galway benefits from the Gaelic football crowd, who play their games at nearby Centennial Park.

James and Sean visited all these pubs, nursing pints of Keith’s, talking to locals and bartenders and letting it be known that they were looking for carpentry work. (They also hung around a sports bar called Shoxs for the simple reason that it was just around the corner from their apartment. Here, they both started dating Canadian-born waitresses. James’s girlfriend is named Erin, Sean’s is Stacey; both are 23 years of age.) About two weeks after coming to Toronto, a bartender at the Galway Arms referred the brothers to an Irishman named Joe Wilson, who owns a company called Clonard Construction. Wilson met with the boys, and by the following Monday they were working at the new condo development at Yonge and Bloor.

“The first thing that struck me about them,” Wilson says today, “was how young they looked. But other than that, they were like all the Irish who come over: they were just desperate for work. It’s a real shock to the system, having to leave home just to find work.”

I recommend the whole article. It provides an interesting look at how migration can be successful and relatively painless. (The big question is how can these social networks be replicated.)

Labels:

canada,

cultural capital,

emigration,

ireland,

labour market,

migration,

sports,

toronto

Wednesday, November 07, 2012

An addendum on demographics and American politics

As the American presidential election seems all but certain to end with an Obama victory based on a wide victory in the Electoral College and near-parity in vote totals, I thought I'd revisit my posting earlier this evening about the Republican Party's significant problems in attracting voters outside of its core white Christian demographics by touching on the comments of Republican-leaning television commentator Bill O'Reilly about the effects of changing demographics on American elections. (I got the quotation from SEK of Lawyers, Guns and Money, here. If it is incomplete or incorrect, please, correct me!)

O’REILLY: All right. Because black birth rate is fairly stable, right?

MCMANUS: Proportionately, black birth rate and increases in their population will level out and be less significant in growth in that time period. I think Bill will be able to address the numbers better than I can, but…

O’REILLY: OK. And how about Asian? What’s the situation with that?

MCMANUS: Asian — we’re going to see a 213 percent increase, according to the Census Bureau projection, and so that will be a very rapid increase of the percentage of their population in the U.S. as well.

O’REILLY: All right. Now, Doctor, the Census Bureau really doesn’t tell us how this is going to affect the country. Do you have any theories on it?

WILLIAM FREY, PH.D., BROOKINGS INSTITUTION: Well, I really think what’s happening is going to be this phasing out or fading out of the white baby boom population. It is a 50-year time period we’re talking about… O’REILLY: Yes. We’ll all be dead. Thank God, right?

"We’ll all be dead. Thank God, right?"

All I can say is that these comments would indicate that O'Reilly, at least, has a profoundly depressing view of the prospects for his favoured party and his country. His preferred ideology and political party aren't capable of convincing people from a wide variety of backgrounds. Instead, they're simply a heritable (but not necessarily inherited?) belief system of a particular group?

Labels:

demographics,

links,

politics,

racism,

united states

On the factor of changing demographics in the 2012 United States election

Last night I shared on my Facebook wall Nate Silver's estimate that the odds were more than nine-to-one in favour of Obama's re-election. We'll see in a few hours how accurate that was. One factor contributing to what, at the very worst for Obama's prospects, would be a very close race will be a demographic factor, specifically the Republican Party's worrisome lack of strength among the United States' large and growing non-white populations. Take Jonathan Martin's Politico article, which starts from the scene of a misleadingly Republican Party rally in Ohio.

Regardless of whether Romney wins or loses, Republicans must move to confront its demographic crisis. The GOP coalition is undergirded by a shrinking population of older white conservative men from the countryside, while the Democrats rely on an ascendant bloc of minorities, moderate women and culturally tolerant young voters in cities and suburbs. This is why, in every election, since 1992, Democrats have either won the White House or fallen a single state short of the presidency.

“If we lose this election there is only one explanation — demographics,” said Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.).

But Republicans are divided on the way forward. Its base is growing more conservative, nominating and at times electing purists while the country is becoming more center than center-right. Practical-minded party elites want to pass a comprehensive immigration bill, de-emphasize issues like contraception and abortion and move on a major taxes-and-spending deal that includes some method of raising new revenue.

[. . .]

“If I hear anybody say it was because Romney wasn’t conservative enough I’m going to go nuts,” said Graham. “We’re not losing 95 percent of African-Americans and two-thirds of Hispanics and voters under 30 because we’re not being hard-ass enough.”

Of the party’s reliance on a shrinking pool of white men, one former top George W. Bush official said: “We’re in a demographic boa constrictor and it gets tighter every single election.”

Poster J.F. at the Economist blog Democracy in America goes into more detail about the precise factors. (Thanks for the link, Leeman.)

As the article explains, "If President Barack Obama wins, he will be the popular choice of Hispanics, African-Americans, single women and highly educated urban whites...it’s possible he will get a lower percentage of white voters than George W. Bush got of Hispanic voters in 2000. A broad mandate this is not." Absolutely. How dare he try to cobble together a majority using blacks, Latinos, single women (not to mention Asians, Jews and gays, all of whom will support Mr Obama by large majorities), "highly educated urban whites" and leave "real" white people out. Perhaps to correct for this strategy we ought to weight non-white votes differently from white votes. Three-fifths has a nice historical ring to it, doesn't it?

Joking aside, here is a fearless prediction: at some point, either tonight or after all the voter data has been collated, a talking head will refer to minority turnout as "unprecedented". These voters, you have no doubt heard, delivered the election to Mr Obama in 2008, and they will be credited again for showing up in such large numbers if he wins tonight. But while Mr Obama's star power may propelling higher minority turnout in the short term, simple demographics is the real cause of the changing electorate. Minority turnout has been "unprecedented" in presidential elections going back to 1988, and it should stay that way for many elections to come.

Pew's Hispanic Centre has dissected the changing face of the electorate. In 1988, whites made up 84.9% of voters; by 2008 that share had dropped to 76.3%. The share of black voters, meanwhile, rose from 9.8% to 12.1%, Hispanics from 3.6% to 7.4% and Asians from unlisted to 2.5%. True, the rise in black voter-share from 2004 to 2008 was quite sharp, and much of it can plausibly be attributed to the thrill of voting for America's first black president. But black voter-share had been rising since Mr Obama was still called Barry.

The broader trend in population is quite similar: the share of whites has been declining as the percentage of blacks, Hispanics and Asians has been rising (see here and here). Prediction is a mug's game, but it hardly counts as going out on a limb to believe that trend will continue. Here's a paper from Pew forecasting that by 2050 Hispanics will comprise nearly one-third of the populace, Asians nearly one-tenth and whites less than half (the black population will remain constant, according to the forecast).

This shift has had a huge impact, undermining many former Republican strongholds. Micah Cohen's post last week at Five Thirty Eight, "In Nevada, Obama, Ryan and Signs of a New (Democratic-Leaning) Normal", goes into more detail about Nevada's changing demographics and changing political trends over the past half-century.

Nevada was once reliably red, favoring the Republican candidate relative to the national popular vote in every presidential election but one — 1960 — from 1948 through 2004. The Silver State’s rightward bent began to dissipate in the 1990s and 2000s. Bill Clinton, a Democrat, carried Nevada in 1992 and 1996, although he was helped by the independent candidacy of Ross Perot, Mr. Damore said.

In 2004, Nevada was almost exactly at the national tipping point, only 0.13 percentage points more Republican-leaning than the nation. Then in 2008, Nevada made the switch. Mr. Obama won nationally by seven percentage points, and he carried the state by 12.5 points. For the first time since 1960, Nevada was more Democratic-leaning than the country.

In 2010, Nevada showed signs that 2008 was not an anomaly. Harry Reid, the Senator majority leader who was battling a Republican wave nationally and poor approval ratings locally, upset expectations (and the polls) to defeat the Republican Sharron Angle in Nevada’s Senate race.

[. . .]

Nevada led the nation in population growth for the past two decades, more than doubling in size to 2.7 million, from 1.2 million in 1990. Fueling that growth has been Democratic-leaning demographic groups: Hispanics, Asians and African-Americans. While Nevada’s non-Hispanic white population grew by 12 percent from 2000 to 2010, African-Americans grew by 58 percent, Asians by 116 percent and Hispanics by 82 percent.

Non-Hispanic whites are still a majority in Nevada, but barely, comprising 54 percent of the state. Hispanics are 27 percent, African-Americans are almost 9 percent, and Asians are about 8 percent.

The state’s booming population has also made Nevada more urban, as the growth has been focused primarily in and around Las Vegas and Reno. Nevada is now the third most urban state in terms of population, according to the 2010 census.

Rural Nevada — which has not seen the population boom that Las Vegas and Reno have — is still overwhelmingly Republican. But it accounts for only about 15 percent of the state population, Mr. Damore said.

Clark County, where Las Vegas is located, is home to more than 70 percent of Nevadans. It is a majority minority county and a Democratic stronghold. The core of Las Vegas is the most left-leaning and predominantly Hispanic and African-American. The Las Vegas suburbs are more politically competitive, similar to suburban communities in Colorado or Virginia, Mr. Damore said.

Why this weakness? Chris Thompson's June article in Rolling Stone, polemical though it may be, places its causes squarely and--I think--accurately--on a fair perception among Hispanics and other groups that the Republican Party doesn't like them very much.

Today, California is competing with Massachusetts and Vermont for the title of bluest state in the Union. Democrats utterly dominate state politics and run all the major cities from north to south, Los Angeles to the Bay Area.

As for the state’s Republicans, they used to roam the freeways and cul-de-sacs in great, thundering herds. Now, they cling to a few isolated enclaves along the beaches of San Diego, farmlands of the Central Valley, and retirement communities near the Oregon border. And they are old and white in a state that's increasingly young and brown.

Two decades of immigration and changing demographics have steadily eroded the Republican base in the Golden State. But rather than adapt to this new reality, the state party lurched deep into the far-right swamplands of American politics. As the state grew more socially liberal, the last of the Republicans doubled down on conservatism, and sank into irrelevancy.

[. . .]

From the late 1960s through the ‘80s, California was a Republican paradise. White suburban families propelled men like Ronald Reagan, Richard Nixon, and governor George Deukmejian to the heights of power, and Orange County, just south of LA, was synonymous with political and cultural conservatism. But by the early 1990s, the Party’s base was growing more and more anxious. The aerospace and defense industries were shriveling, and metropolitan liberals were spilling over from Hollywood and San Francisco, transforming cities like San Jose from farm communities into expensive high-tech centers. In the biggest and most visible shift, the Latino population was surging, making up 25 percent of the state’s population by 1990.

In 1994, incumbent Gov. Pete Wilson, a Republican, faced a tough reelection fight. The recession was still lingering in California, and he had to answer for it. His Democratic challenger was Kathleen Brown, the sister of Jerry Brown and a tough political fighter. Wilson needed something to distract voters from the economy – something that would spook enough of them into rallying behind him.

He found it. Wilson pulled his campaign together by running on two divisive state ballot initiatives – Proposition 184, the notorious "Three Strikes" law, which played into suburban residents’ fear of crime, fears stirred up by the Rodney King riots just two years earlier; and the sinister Proposition 187 – the "Save our State" initiative, which conjured images of parasitical Latinos swarming into California and proposed denying social services such as public education and some medical care to the children of illegal immigrants.

"They had a famous ad that showed undocumented immigrants streaming across the border, and it was sort of the rats streaming onto the ship," says Bruce Cain, a UC Berkeley political science professor and longtime observer of California politics. "It was extremely offensive, but it worked for Pete Wilson."

Did it ever. Not only did Wilson win reelection, the Republicans made historic gains in the state legislature, winning a majority in the state Assembly for the first time in years. But the strategy would prove to be the white sugar of California politics: tasty in the short term, but disastrous in the years ahead.

As the 1990s wore on, Republicans overplayed their hand, pushing one racially-tinged wedge issue after another at the ballot box, banning Affirmative Action, ending bilingual education in the public schools, and enacting a new round of draconian punishments for juvenile delinquents. They rode these propositions to victory, but alienated the Latino population and propelled a wave of white resentment that now defines Republican politics. "It was a case of, 'Hey this worked, let’s keep pushing that button,'" Cain says. "But once you start doing that, you unleash forces within your own party that you can’t really control."

[. . .]

Aside from Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger – who was elected only by dint of a bizarre recall circus in 2003, and was despised by his own conservative base – almost no Republican has won statewide office since the mid-1990s. From Latinos to black voters and urban professionals, the Republican Party managed to alienate every growing segment of California society, all for the sake of inflaming the passions of the one demographic group that was actually shrinking.

[. . .]

Now, the damage is clear. Latinos comprise 37.6 percent of California’s population, and years of demonization at the hands of Republicans have compelled millions of them to register and vote. Democrats enjoy a 52-27 majority in the Assembly, and a 21-17 majority in the Senate. From United States Senator to Governor, Lieutenant Governor, and Attorney General, every single major statewide office is occupied by a Democrat. Meanwhile, the latest presidential polling has Obama up on Romney among Latinos by a staggering 57-15 percent.

It goes without saying that it's very worrisome when one of the political parties in a country with a two-party political system is unable to attract the support of large, growing, and increasingly visible proportions of the country's population.

Thoughts?

Labels:

demographics,

links,

politics,

united states

Tuesday, October 30, 2012

On how playing with the census creates problems with the data, cf Canada 2011

The results of the 2011 Canadian census are in, and informative press releases have been coming out, like the release of the 24th of October outlining the changing patterns of language spoken and used in Canada.

There's a problem. I made a series of posts at Demography Matters concentrating on how the desire of the incumbent federal government in Canada to abolish the long-form census, putting questions on identity and such matters off to a voluntary form, would damage the integrity of the data series. Well, as reported by CBC, that happened.

Forgive the extended quote, but it's necessary to make the point.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper's cancellation of the long-form census has started to take a toll on Statistics Canada's data.

The agency released its final tranche of the 2011 census last week, focusing on languages, but it included a big warning that cautions data users about comparing key facts against censuses of the past.

"Data users are advised to exercise caution when evaluating trends related to mother tongue and home language that compare 2011 census data to those of previous censuses," Statistics Canada states bluntly in a box included in its census material.

[. . .]

In the past, the language questions were mostly included in the long form, which went to 20 per cent of households. When Harper cancelled the long form, several groups concerned about tracking the vibrancy of French in Canada went to court to make sure information about official language usage was properly collected.

As a result, the Harper government agreed to move the language questions to the short form, which went to 100 per cent of households.

The problem was that the language questions in 2011 were presented in a different context than they were in 2006, explained [Jean-Pierre Corbeil, the lead analyst for the languages part of the 2011 census]. In 2006, they were preceded by other questions about ethnicity and birthplace. Now, they appear suddenly after basic demographic questions.

The context of the questions has changed dramatically, likely prompting people to answer the questions truthfully, but differently, Corbeil said.

"We reviewed everything. Everything is really OK. The only thing is, we know that the responses we get are really influenced by the context and the placement in our questionnaires."

The main problems arise in how respondents reported their mother tongue and the language they spoke at home. Based on what Statistics Canada knows about immigration, there were far too many people claiming to have two mother tongues -- an official language plus a non-official language -- and speak an official language plus another language at home.

What first set off alarm bells for Corbeil was the proportion of people reporting English as a mother tongue. The raw data from the 2011 census told him it was 58 per cent. That was the same percentage as in 2006, but in the meantime, Canada had received about 1.1 million new immigrants.

And Citizenship and Immigration data, as well as Statistics Canada's own research, told him that 80 per cent of those immigrants did not have English or French as a mother tongue.

If people had responded to the 2011 census in the same way as the 2006 census, the proportion of English-speakers "would have been lower," Corbeil said.

He looked further and found more strangeness. Between 2001 and 2006, the census found there was an increase of 946,000 in the number of people who claimed a non-official language as a mother tongue. But between 2006 and 2011, that number dropped to 420,000.

That's less than half the increase noted earlier in the decade, even though immigration levels continued to rise at the same rate.

Friday, August 24, 2012

On the potential consequences of open borders and wages

A recent post made by Chris Bertram at Crooked Timber, "Open borders, wages, and economists", raises some interesting questions. There's substantial agreement on the benefits of radically liberalized immigration policies on potential migrants. What of consequences on workers in the receiving countries?

One author, Michael Clemens, raises the possibility of a doubling of global income (PDF); another, John Kennan, envisages a doubling of the incomes of the migrants. Either way, the gains are huge: put those poor people into the institutional and capital contexts of wealth countries and they would do much much better.The discussion in the comments is worth reading.

What there seems to be much less agreement on is the effect of open borders on the wages of the non-migrant population of the wealthy receiving countries. Clemens and Kennan generally concede the possibility of some small depressive effect but argues that it would be temporary and/or could be compensated for at a policy level by suitable taxes and transfers. This is a radically different story from that told by, for example, Ha-Joon Chang, in his book 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism . Chang’s third “thing”, “Most people in rich countries are paid more than they should be” contains a parable of two bus drivers, Ram in India and Sven in Sweden. They do similar jobs, but if anything Ram’s requires more skill as he “has to negotiate his way almost every minute of his driving though bullock carts, rickshaws and bicyles stacked three metres high with crates.”(25) Yet Sven is paid 50 times more than Ram is (and it would be easy to find examples where the pay divergence is much larger, perhaps as much as 1000 times between unskilled labourers in poor and wealthy countries). Chang things it implausible that Sven embodies more human capital than Ram does as a result of education and training, since most of his Swedish education is irrelevant to what he does on the job.

So if Chang is right, an open border policy would have a massive depressive effect on the earnings of non-migrant workers in wealthy countries since other people would be happy to take unskilled or low-skilled jobs for much less than the current wage (but more than they could get at home).

Given the massive aggregate welfare gains from migration, perhaps supplemented by other thoughts about human rights and freedom of movement, some peope will argue that open borders is the right policy regardless of its effects on the poor citizens of wealthy countries. And they may be right about that. But clearly if we are to wage a political battle for more liberal immigration policies in Festung Europa and the United States, then the truth about the benefits or harms to the existing population is important. It is one thing to say to an electorate that free migration will probably not harm them (and may even benefit them) and quite another to say that such harms as they suffer are swamped by the benefits in a global utilitarian calculus. The first stands a chance of democratic success; the latter, realistically, has none.

Labels:

demographics,

economics,

labour market,

migration

Wednesday, August 22, 2012

A second note on the import of statistics

My post last Monday about basic demographic figures only being indicative of possible futures, not determinative of them. This does not mean that numbers are not important.

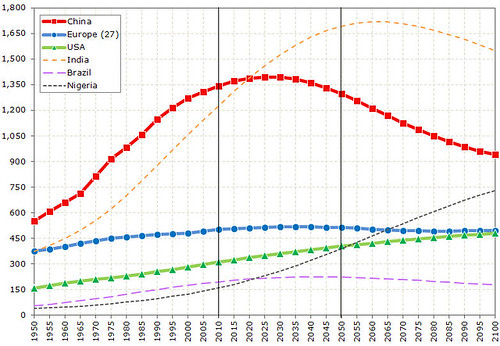

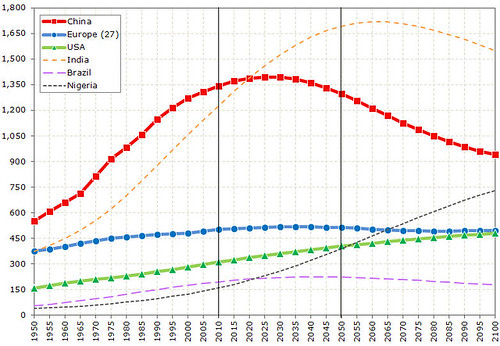

Taken from here, this chart shows the effects of differential population change over the 1950-2100 period, using United Nations data from 2010. The site's summation merits sharing.

A glance at Wikipedia's list of the populations of the countries of the world over time confirms this. In 1950, the United States' 151.9 million would have been outnumbered two-to-one by the 68.4 million of Germany, 50.1 million of the United Kingdom, 47.1 million of Italy, 42.5 million of France, and 28.1 million of Spain. Looking outside of the North Atlantic area, there were barely more Brazilians than there were Britons and Italians, war-devastated Poland's 24.8 millions comfortably outnumbered Egypt's 21.9 million inhabitants, the Netherlands had 30-40% fewer inhabitants than Canada or South Africa, Singapore had barely a million residents, and the populations of the smaller Persian Gulf states were measurable in hundreds of thousands or even tens of thousands.

Europe's populations grew absolutely, and quite substantially, but declined relative to the rest of the world as the demographic transition took hold, with greater effect owing to the superior medical technology and sharply reduced infant mortality available in our time, as opposed to a century ago. This decline manifested even relative to other high- and middle-income continents and countries. On Tuesday, Slate noted that day was "Pi Day", that shortly after 2:29 pm Eastern Standard Time United States Census Bureau's population clock hit 314 159 265--"pi times 10 to the eighth", as Slate notes--according to a press release. On that day, it should be noted, the five European countries that together outnumbered the United States two-to-one sixty-two years ago now lead the United States by just a couple million people. Soon, these five countries' lead will disappear; soon, the United States will lead.

Looking at the simple crude metric of total population says nothing about other, arguably more important factors, like (say) age composition. (To name a single example, Nigeria is going to be so much younger than China in 2050.) By themselves, these population totals don't mean anything. It's imaginable that Nigerian economic weight wouldn't equal its demographic weight, arguably likely given its problems and current leadership. But having a population on the order of China's and Europe's, and younger than either, makes the chances of such growth that much more likely.

Taken from here, this chart shows the effects of differential population change over the 1950-2100 period, using United Nations data from 2010. The site's summation merits sharing.

The population of the United States of America is projected to grow continuously for many decades to come. By the end of the century the US population will be approximately the same size as that of the 27 states that make up the European Union.

China's population, on the other hand will only slightly grow (due to its momentum effect) until around 2025. Then it will start to decline significantly until it will reach a bit more than 900 million.

For comparison: India's population will outgrow that of China by 2020 and then further increase to more than 1.7 billion around 2065. Only then it is projected to start declining.

A most dramatic demographic change is projected for the most populous country in Africa: Nigeria. While its population was only around 38 million in 1950, it has now increased to about 150 million and is projected to reach almost 750 million by the end of the century. Shortly after 2050 Nigeria's population will become larger than the (growing) population of the United States; and by 2065 Nigeria's population will outgrow the population of the 27 states of the European Union combined. In fact, around 2070 Nigeria's population will be as large as China's population in 1950.

India is another country with remarkable population growth: By 1950 India's population was almost exactly the same size as that of the 27 countries of the European Union combined. Today India has four times as many people and by around 2060, India's population will be 3.4 times that of Europe. Within about one century, India's population has outgrown Europe's population by 1.2 billion people.

These fundamental discrepancies in population growth will shift the geo-strategic weight away from Europe towards Asia and Africa.

A glance at Wikipedia's list of the populations of the countries of the world over time confirms this. In 1950, the United States' 151.9 million would have been outnumbered two-to-one by the 68.4 million of Germany, 50.1 million of the United Kingdom, 47.1 million of Italy, 42.5 million of France, and 28.1 million of Spain. Looking outside of the North Atlantic area, there were barely more Brazilians than there were Britons and Italians, war-devastated Poland's 24.8 millions comfortably outnumbered Egypt's 21.9 million inhabitants, the Netherlands had 30-40% fewer inhabitants than Canada or South Africa, Singapore had barely a million residents, and the populations of the smaller Persian Gulf states were measurable in hundreds of thousands or even tens of thousands.

Europe's populations grew absolutely, and quite substantially, but declined relative to the rest of the world as the demographic transition took hold, with greater effect owing to the superior medical technology and sharply reduced infant mortality available in our time, as opposed to a century ago. This decline manifested even relative to other high- and middle-income continents and countries. On Tuesday, Slate noted that day was "Pi Day", that shortly after 2:29 pm Eastern Standard Time United States Census Bureau's population clock hit 314 159 265--"pi times 10 to the eighth", as Slate notes--according to a press release. On that day, it should be noted, the five European countries that together outnumbered the United States two-to-one sixty-two years ago now lead the United States by just a couple million people. Soon, these five countries' lead will disappear; soon, the United States will lead.

Looking at the simple crude metric of total population says nothing about other, arguably more important factors, like (say) age composition. (To name a single example, Nigeria is going to be so much younger than China in 2050.) By themselves, these population totals don't mean anything. It's imaginable that Nigerian economic weight wouldn't equal its demographic weight, arguably likely given its problems and current leadership. But having a population on the order of China's and Europe's, and younger than either, makes the chances of such growth that much more likely.

Monday, August 13, 2012

On demographics as only one starting point

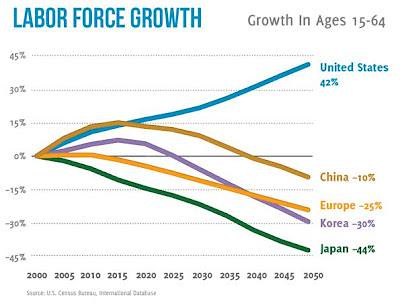

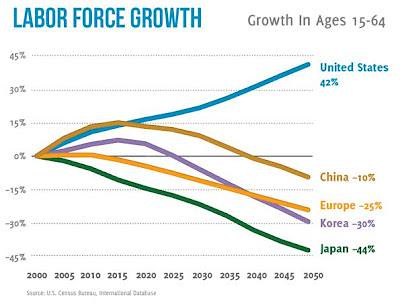

I've intended for some time comment upon Cam Hui's Seeking Alpha "America's 'Trente Glorieuses'"?. It makes a fairly common argument: the United States, by virtue of its particular demographic structure, enjoys a significant advantage over its various peers and competitors.

My main quibble with this graphic in that it doesn't break "Europe" down into more meaningful national units--Britain is not France is not Germany is not Spain is not Poland, continent-wide convergence in demographic trends being far from complete--but otherwise, yes, I buy the points being made. The United States does stand out among high- and middle-income countries for its demographic profile, characterized by high rates of natural increase and substantial net migration in a population that's already young. If most of the United States' peers and competitors have populations aging much more rapidly than the United States, with obvious consequences for the relative availability of labour and costs for supporting non-economically productive populations, the United States has a decided advantage. Overall, as the Economist noted, fertility in Europe has fallen after a brief recovery in the past decade. The other countries cited by Hui as major competitors--China, Korea, Japan--all seem to be on track for ultra-low fertility, while many other economic competitors are on track for, at best, replacement-level fertility.

(Parenthetically, it should be noted that the United States is not completely unique. For instance, Behind the Numbers' Carl Haub notes that American fertility has fallen slightly recently in response to the recession, the Economistadding by noting that TFRs in France and England have been rising for some time and are now higher than the United States' figure. These two exceptions don't change the overall picture that much.)

What's my problem with Hui's analysis? It's two-fold.

On one level, I find his use of the term Trente Glorieuses to be misleading in reference to the sorts of demographic changes described. In France at least, the Trente Glorieuses saw a thorough transformation of the structure of France's population, the low growth that characterized the Third Republic being transformed by the combined effects of the strong baby boom and high levels of immigration and intensified rural-to-urban migration. The basic trends afoot with France's demographic structure changed completely, in other words. Hui, in contrast, is describing a situation where the basic underlying trends of the United States' demographic structure remain unchanged, where there the only transformation lies outside the United States, specifically in other countries' developing more disadvantageous demographic structures.

My deeper problem with Hui's analysis is that it takes simple numbers to mean too much. Hui is quite right to point out that the continued growth in the United States' population of working age has the potential to offer it a significant advantage over other upper- and middle-income countries, but will this potential necessarily be realized? "Demography matters" is the name of this blog, yes, but no one posting here has ever argued that the demographic structure of a population determines everything about a given population's economic future. Governments can craft policies to take advantage of demographic sweet spots or not, can craft policies which deal which deal successfully with particular demographic issues or not.

* The rapid transition of China over the past generation from high to below-replacement fertility rates did give China significant economic advantages in the context of the pro-market policies of Deng Xiaopeng and his successors, for instance, but was the embrace of these pro-market policies solely determined by China's demographic transition? Clearly, no. China could have enacted the one-child policy but not enacted pro-market policies, for instance.

* Is it imaginable that, in the future, the United States might fail to take advantage of its continued demographic advantages while its peers and competitors might make better use of their more limited resources? Clearly, yes. Most of the countries of the Soviet bloc squandered, for reasons of ideology and power politics, their own demographic sweet spots.

* For that matter, could these population projections be off? It's conceivable. In the longer term, fertility rates could change significantly and lead to slow change--they could fall in the United States and rise in Germany, as norms and policies changed. In the shorter term, immigration could induce significant changes, as the experience of Spain over the past decade suggests. (How likely might these shifts be? They're in the realm of the possible, at least.)

Demographics can only ever be a starting point, only one element in a complex array of variables which all interact with each other. It's an important element, yes, but it shouldn't be read as the determinative one.

One of the graphics used to illustrate the article is this one, showing projected growth in the 15-to-64 working age demographic in the half-century to 2050.

In the post-war period starting from 1945, France and much of Western Europe experienced a virtual cycle of rapid economic growth lasting thirty years called les trente glorieuses. Economic growth was driven by the combination of rising working age population, incomes and standards of living. This is known as a "demographic dividend".

America may be on the verge of its own trente glorieuses as it experiences its own demographic dividend, driven by the combination of a rising working age population as the children of the post-war Baby Boomers grow up and enter the work force and immigration.

The American age demographic profile is substantially better than its major trading partners. Despite the angst over dependency ratios, or the ratio of workers to retirees, the expected increase in American workers means that American dependency ratios are likely to stabilize in the decades to come, whereas those of many other countries continue to decline – which will strain the pension system and national finances.

America's relative youthfulness compared to trading partners isn't just a product of its higher birthrate, it is also a function if its willingness to accept immigration. The United States and Canada are in the minority of major industrialized countries that openly accept immigrants.

Indeed, BBVA research (via Business Insider) titled 'Immigrants rejuvenate the United States' show that without the influx of Mexican immigrants, the demographic of the U.S. would be much, much older[.]

My main quibble with this graphic in that it doesn't break "Europe" down into more meaningful national units--Britain is not France is not Germany is not Spain is not Poland, continent-wide convergence in demographic trends being far from complete--but otherwise, yes, I buy the points being made. The United States does stand out among high- and middle-income countries for its demographic profile, characterized by high rates of natural increase and substantial net migration in a population that's already young. If most of the United States' peers and competitors have populations aging much more rapidly than the United States, with obvious consequences for the relative availability of labour and costs for supporting non-economically productive populations, the United States has a decided advantage. Overall, as the Economist noted, fertility in Europe has fallen after a brief recovery in the past decade. The other countries cited by Hui as major competitors--China, Korea, Japan--all seem to be on track for ultra-low fertility, while many other economic competitors are on track for, at best, replacement-level fertility.

(Parenthetically, it should be noted that the United States is not completely unique. For instance, Behind the Numbers' Carl Haub notes that American fertility has fallen slightly recently in response to the recession, the Economistadding by noting that TFRs in France and England have been rising for some time and are now higher than the United States' figure. These two exceptions don't change the overall picture that much.)

What's my problem with Hui's analysis? It's two-fold.

On one level, I find his use of the term Trente Glorieuses to be misleading in reference to the sorts of demographic changes described. In France at least, the Trente Glorieuses saw a thorough transformation of the structure of France's population, the low growth that characterized the Third Republic being transformed by the combined effects of the strong baby boom and high levels of immigration and intensified rural-to-urban migration. The basic trends afoot with France's demographic structure changed completely, in other words. Hui, in contrast, is describing a situation where the basic underlying trends of the United States' demographic structure remain unchanged, where there the only transformation lies outside the United States, specifically in other countries' developing more disadvantageous demographic structures.

My deeper problem with Hui's analysis is that it takes simple numbers to mean too much. Hui is quite right to point out that the continued growth in the United States' population of working age has the potential to offer it a significant advantage over other upper- and middle-income countries, but will this potential necessarily be realized? "Demography matters" is the name of this blog, yes, but no one posting here has ever argued that the demographic structure of a population determines everything about a given population's economic future. Governments can craft policies to take advantage of demographic sweet spots or not, can craft policies which deal which deal successfully with particular demographic issues or not.

* The rapid transition of China over the past generation from high to below-replacement fertility rates did give China significant economic advantages in the context of the pro-market policies of Deng Xiaopeng and his successors, for instance, but was the embrace of these pro-market policies solely determined by China's demographic transition? Clearly, no. China could have enacted the one-child policy but not enacted pro-market policies, for instance.

* Is it imaginable that, in the future, the United States might fail to take advantage of its continued demographic advantages while its peers and competitors might make better use of their more limited resources? Clearly, yes. Most of the countries of the Soviet bloc squandered, for reasons of ideology and power politics, their own demographic sweet spots.

* For that matter, could these population projections be off? It's conceivable. In the longer term, fertility rates could change significantly and lead to slow change--they could fall in the United States and rise in Germany, as norms and policies changed. In the shorter term, immigration could induce significant changes, as the experience of Spain over the past decade suggests. (How likely might these shifts be? They're in the realm of the possible, at least.)

Demographics can only ever be a starting point, only one element in a complex array of variables which all interact with each other. It's an important element, yes, but it shouldn't be read as the determinative one.

Labels:

demographics,

fertility,

france,

labour market,

migration,

united kingdom,

united states

Saturday, July 07, 2012

On the United Kingdom, the European Union, the Commonwealth, and migration issues

News that the British government is considering ways to keep Greek citizens from entering the United Kingdom if it seems they might enter the country in large numbers has gotten a strong reaction.

The British Prime Minister, David Cameron, is prepared to override Britain's historic obligations under European Union treaties and impose stringent border controls that would block Greek citizens from entering Britain, if Greece is forced out of the single currency.

The Prime Minister told MPs that ministers have examined legal powers that would allow Britain to deprive Greek citizens of their right to free movement across the EU, if the eurozone crisis leads to ''stresses and strains''.

In an appearance before senior MPs on the cross-party House of Commons liaison committee, Mr Cameron confirmed that ministers have drawn up contingency plans for ''all sorts of different eventualities''.

The worst-case scenario is understood to cover a Greek exit from the euro, which could trigger a near-collapse of the Greek economy and the flight of hundreds of thousands of its citizens who are entitled to settle in any EU country.

[. . .]

Asked by Keith Vaz, the Labour chairman of the Commons home affairs select committee, whether he would restrict the rights of Greek citizens to travel to Britain, Mr Cameron said he would be prepared to trigger such powers.

[. . .]

''You have to plan, you have to have contingencies, you have to be ready for anything - there is so much uncertainty in our world. But I hope those things don't become necessary.''

Leaving aside the expectedly heated reaction from Greece that caught my attention, but the reaction of non-British, non-Greek Europeans who I saw react to the article on Facebook. A United Kingdom that chose to opt out of the single market's freedom of movement for workers even on a temporary basis, after staying out of the Eurozone and Schengen Zone blocs from their foundations and acquiring a reputation (fairly or not) for being hostile to European Union integration on principle, might not find itself very popular elsewhere in the European Union. Perhaps--who knows?--if the United Kingdom ever did hold a referendum on continued EU membership, Europeans might welcome British departure? Famously anti-immigration groups like Migration Watch don't emphasize immigration from elsewhere in the European Union as much of an issue, noting that migrants form elsewhere in the European Union form perhaps three-tenths of the total number of immigrants to the United Kingdom at present and assuming that the volume of this migration and number of permanent migrant wills fall as central and southeastern Europe develop. As the Conservative government finds its restrictive net migration target difficult to achieve, even the Labour Party's Ed Milliband starting to agree with the current British government's migration policies, the idea of limiting migration from other European Union countries--perhaps temporarily, at first--might become popular.

What interests me about the dislike of many Britons with the volume of migration from elsewhere in the European Union (not to other EU member-states, mind), is that it's strongly associated with opposition to the United Kingdom's membership in the European Union. The United Kingdom, a certain vein of argument holds (see Nile Gardiner in The Telegraph, for instance), was tricked into joining an anti-democratic European bloc that had goals of supranational integration that Britons never wanted. Britain can withdraw from the European Union comfortably, knowing that the continent is in decline anyway as the BRICS and the rest grow, and instead turn to the Commonwealth of Nations that it unnecessarily reoriented itself from in the 1970s, with its use of the English language and shared history under Britain and promising economies (developed like Canada's or Australia's, developing like India's or South Africa's), and thrive in a revived Commonwealth.

There are many problems with this project. (Speaking as a citizen of a Commonwealth country, the basic assumption of these people that Britain's former colonies are going to be interested in restoring the privileged relationships of the past when they're now mature countries with relationships of their own, thank you very much, is a huge one.) The demographic-related problem with this? Migration Information's July 2009 country profile of the United Kingdom noted accurately that the two countervailing trends in post-Second World War immigration to the United Kingdom has been the lowering of barriers to migration from the European Union and barriers' simultaneous raising to the countries of the Commonwealth. Britain passed multiple laws in the post-war period progressively making it more difficult for citizens of other Commonwealth countries to settle in the United Kingdom, most famously in the 1980s and 1990s constructing a citizenship for British Hong Kong that made it impossible for British citizens in the last major colony to immigrate to the United Kingdom at a time when countries around the world were competing for the wealthy, skilled migrants from Hong Kong who wanted to leave before reunificatiion with China in 1997. The restrictions on migrants from the Commonwealth, as far as I can tell, have very little to do with the United Kingdom's membership in the European Union and everything to do with opposition to immigration generally. If New Zealand's agricultural exports no longer had privileged access to British markets after 1973, it didn't follow that New Zealand's citizens likewise had to be excluded from privileged access to the territory and labour markets of the former metropole. The nationality law of Spain even now gives residents of Spain's former Latin American and Asian colonies access to expedited naturalization, no matter that many of these countries have been fully independent for nearly two centuries.

(I myself lack the right of abode in the United Kingdom, having been a Canadian citizen on 31 December 1982 but whose last British born relatives died this time last century at the very latest.)

All this brings me to Ruth Grove-White's essay on the connections between British immigration policies and British relationships with the Commonwealth, originally posted at Migrants Rights and reposted at Open Democracy.

The direction of UK policy indicates that efforts to slash net migration will have significant impacts on Commonwealth migrants - and potentially wider implications for inter-governmental relationships. The coalition government’s cap on non-EU migrant workers, for example, caused immediate and embarrassing ripples for relations with key Commonwealth governments when it was announced in 2010. New restrictions on international students including closure of the post-study work route from this April, given that two thirds of new Commonwealth citizens coming to the UK currently come for study, can be expected to affect these nationals in particular.

And upcoming rule changes on family migration, in particular a new income threshold for applicants which could prevent up to half of the UK’s working population from bringing a family member here, would particularly impact on nationals of Pakistan, Bangladesh, India and Nepal who are the big users of the family migration route currently. These rule changes may satisfy the immediate government policy agenda, but they are viewed as unfair among many from diaspora communities based here.

As these developments take shape over the coming period, we can and should expect immigration to play a more central role in discussion about the Commonwealth and Britain today - what will the implications of today's policies be on future communities and their perceptions of national identity and British institutions? It would be worth considering whether, rather than connecting cultures, the UK is instead creating new barriers - and new challenges - into the future.

Will Commonwealth countries whose citizens are kept from working and living in the United Kingdom on a scale unprecedented even now going to be open to developing otherwise close relations with the United Kingdom if it leaves the European Union? I have grave doubts. Opponents of British membership in the European Union should keep this in mind when they draw up optimistic plans for a non-EU Britain's future.

The British Prime Minister, David Cameron, is prepared to override Britain's historic obligations under European Union treaties and impose stringent border controls that would block Greek citizens from entering Britain, if Greece is forced out of the single currency.

The Prime Minister told MPs that ministers have examined legal powers that would allow Britain to deprive Greek citizens of their right to free movement across the EU, if the eurozone crisis leads to ''stresses and strains''.

In an appearance before senior MPs on the cross-party House of Commons liaison committee, Mr Cameron confirmed that ministers have drawn up contingency plans for ''all sorts of different eventualities''.

The worst-case scenario is understood to cover a Greek exit from the euro, which could trigger a near-collapse of the Greek economy and the flight of hundreds of thousands of its citizens who are entitled to settle in any EU country.

[. . .]

Asked by Keith Vaz, the Labour chairman of the Commons home affairs select committee, whether he would restrict the rights of Greek citizens to travel to Britain, Mr Cameron said he would be prepared to trigger such powers.

[. . .]

''You have to plan, you have to have contingencies, you have to be ready for anything - there is so much uncertainty in our world. But I hope those things don't become necessary.''

Leaving aside the expectedly heated reaction from Greece that caught my attention, but the reaction of non-British, non-Greek Europeans who I saw react to the article on Facebook. A United Kingdom that chose to opt out of the single market's freedom of movement for workers even on a temporary basis, after staying out of the Eurozone and Schengen Zone blocs from their foundations and acquiring a reputation (fairly or not) for being hostile to European Union integration on principle, might not find itself very popular elsewhere in the European Union. Perhaps--who knows?--if the United Kingdom ever did hold a referendum on continued EU membership, Europeans might welcome British departure? Famously anti-immigration groups like Migration Watch don't emphasize immigration from elsewhere in the European Union as much of an issue, noting that migrants form elsewhere in the European Union form perhaps three-tenths of the total number of immigrants to the United Kingdom at present and assuming that the volume of this migration and number of permanent migrant wills fall as central and southeastern Europe develop. As the Conservative government finds its restrictive net migration target difficult to achieve, even the Labour Party's Ed Milliband starting to agree with the current British government's migration policies, the idea of limiting migration from other European Union countries--perhaps temporarily, at first--might become popular.

What interests me about the dislike of many Britons with the volume of migration from elsewhere in the European Union (not to other EU member-states, mind), is that it's strongly associated with opposition to the United Kingdom's membership in the European Union. The United Kingdom, a certain vein of argument holds (see Nile Gardiner in The Telegraph, for instance), was tricked into joining an anti-democratic European bloc that had goals of supranational integration that Britons never wanted. Britain can withdraw from the European Union comfortably, knowing that the continent is in decline anyway as the BRICS and the rest grow, and instead turn to the Commonwealth of Nations that it unnecessarily reoriented itself from in the 1970s, with its use of the English language and shared history under Britain and promising economies (developed like Canada's or Australia's, developing like India's or South Africa's), and thrive in a revived Commonwealth.

There are many problems with this project. (Speaking as a citizen of a Commonwealth country, the basic assumption of these people that Britain's former colonies are going to be interested in restoring the privileged relationships of the past when they're now mature countries with relationships of their own, thank you very much, is a huge one.) The demographic-related problem with this? Migration Information's July 2009 country profile of the United Kingdom noted accurately that the two countervailing trends in post-Second World War immigration to the United Kingdom has been the lowering of barriers to migration from the European Union and barriers' simultaneous raising to the countries of the Commonwealth. Britain passed multiple laws in the post-war period progressively making it more difficult for citizens of other Commonwealth countries to settle in the United Kingdom, most famously in the 1980s and 1990s constructing a citizenship for British Hong Kong that made it impossible for British citizens in the last major colony to immigrate to the United Kingdom at a time when countries around the world were competing for the wealthy, skilled migrants from Hong Kong who wanted to leave before reunificatiion with China in 1997. The restrictions on migrants from the Commonwealth, as far as I can tell, have very little to do with the United Kingdom's membership in the European Union and everything to do with opposition to immigration generally. If New Zealand's agricultural exports no longer had privileged access to British markets after 1973, it didn't follow that New Zealand's citizens likewise had to be excluded from privileged access to the territory and labour markets of the former metropole. The nationality law of Spain even now gives residents of Spain's former Latin American and Asian colonies access to expedited naturalization, no matter that many of these countries have been fully independent for nearly two centuries.

(I myself lack the right of abode in the United Kingdom, having been a Canadian citizen on 31 December 1982 but whose last British born relatives died this time last century at the very latest.)

All this brings me to Ruth Grove-White's essay on the connections between British immigration policies and British relationships with the Commonwealth, originally posted at Migrants Rights and reposted at Open Democracy.

The direction of UK policy indicates that efforts to slash net migration will have significant impacts on Commonwealth migrants - and potentially wider implications for inter-governmental relationships. The coalition government’s cap on non-EU migrant workers, for example, caused immediate and embarrassing ripples for relations with key Commonwealth governments when it was announced in 2010. New restrictions on international students including closure of the post-study work route from this April, given that two thirds of new Commonwealth citizens coming to the UK currently come for study, can be expected to affect these nationals in particular.

And upcoming rule changes on family migration, in particular a new income threshold for applicants which could prevent up to half of the UK’s working population from bringing a family member here, would particularly impact on nationals of Pakistan, Bangladesh, India and Nepal who are the big users of the family migration route currently. These rule changes may satisfy the immediate government policy agenda, but they are viewed as unfair among many from diaspora communities based here.

As these developments take shape over the coming period, we can and should expect immigration to play a more central role in discussion about the Commonwealth and Britain today - what will the implications of today's policies be on future communities and their perceptions of national identity and British institutions? It would be worth considering whether, rather than connecting cultures, the UK is instead creating new barriers - and new challenges - into the future.

Will Commonwealth countries whose citizens are kept from working and living in the United Kingdom on a scale unprecedented even now going to be open to developing otherwise close relations with the United Kingdom if it leaves the European Union? I have grave doubts. Opponents of British membership in the European Union should keep this in mind when they draw up optimistic plans for a non-EU Britain's future.

Friday, June 22, 2012

Some Friday demographics blog links

The Burgh Diaspora builds from the brief Demography Matters post I made Monday, about the likelihood of the resumption of patterns of migration from Mediterranean to northern Europe regardless of what happens to the Eurozone, and wonders why people won't also migrate from Mediterranean Europe to points elsewhere in the world, to potentially more lucrative destinations than Germany--Brazil, say.

The answer to that is that this migration is already ongoing to some extent, perhaps most visibly with migration from Portugal to Brazil and Angola. Migration from Mediterranean Europe to points elsewhere--to Latin America, to the Middle East, to Eat Asia--is ongoing and likely to accelerate. The European Union's frontiers are hardly impenetrable, and different Europeans do have different degrees of connection to non-European Union societies and economies that haven't been erased. (The interest of some Greeks and Irish in moving to Canada and Australia comes to mind as another point.)

Crooked Timber's Chris Bertram was unhappy with new immigration provisions proposed in the United Kingdom, based on financial and language requirements that the majority of Britons wouldn't meet. Press reports, from The Independent for instance, seem to indicate that the basic principles of this policy are going to be enacted, part of the United Kingdom's swing towards a strongly anti-immigration policies. (Ed Milliband of Labour is also in favour of strict immigration controls, albeit not the ones under discussion.

Eastern Approaches visited northwestern Bulgaria and finds a declining region kept afloat by mass migration, to Bulgarian cities and to the wider European Union.