In a seminal paper [1] from 1958 Franco Modigliani and Merton H Miller showed why investors should not care about whether firms were financed with debt or equity. This led to the idea of the the debt irrelevance proposition and although the DIP is a theoretical benchmark rather than a real world rule the 1958 paper by Modigliani and Miller remains a key contribution to the finance literature. We should not however extend the same role to the recent attempt by researchers [2] to re-invent the DIP in a new guise replacing "debt" by "demographics". Allow me to explain why.

Demographics, Just Forget About It ...

My point of departure is Edward Chancellor's recent GMO letter in which he tackles what he considers to be the non-issue of Japan's dire demographics. He emphasizes two things; firstly, that economists are notoriously poor at predicting demographic variables and secondly he notes that whatever relevance demographics might have for macroeconomic analysis at large (of which Mr Chancellor appears skeptical) it is irrelevant for the investor;

Besides, long-term demographic forecasts aren’t particularly relevant for equity investors. It’s true that changes in the population have a sizable impact on GDP growth. But stock market returns are not positively correlated with economic growth. Returns from equities are a function of valuation and future returns on capital – a subject to which I will return later – rather than changes in GDP. Nor is there a positive correlation between population growth and stock market returns. In short, investors should not get too hung up on inherently unreliable long-term demographic projections for Japan.

It is important to underline, in fairness to Chancellor, that the points are made with specific focus on Japan but the the argument seems to have a more general hue. This is even more obvious in relation to one of Chancellor's main references in the form of Morgan Stanley analyst Alexander Kinmont's note entitled The Irrelevance of “Demographics”? Kinmont puts up the following four points which I will use as my points of reference;

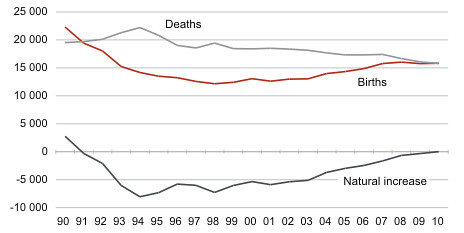

1. It is not clear that demographic estimates are accurate over long time frames. In fact, while spurious specificity is one of the attractions of demographics as a talking point, the fact that neither death rates nor birth rates have proven predictable should caution one against accepting any assertion about demographics.

2. It is not clear that demographics are the critical variable in determining the level of economic growth. That role falls to the growth rate of TFP.

3. It is not clear that equity returns are related to absolute levels of growth. Equity returns are an issue of valuation. Nominal returns are greatly affected by inflation too.

4. It is not clear that demographic change, even if it is allowed as a negative for economic growth, is necessarily negative for stocks, as certain forms of demographic change may be associated with a rising equity market multiple. Demographic change could in fact represent a benign environment for stocks.

On the first point Kinmont makes points to the irony in that the worry about Japanese demographics seems to be peaking just as Japanese fertility is on the mend. This is a cheap shot though and not one which stands up to scrutiny. First of all on the fertility trend itself I get the same chart as Kinmont's below using data from the World Bank showing a rebound in Japan from a low point of 1.29 in 2003 and 2004 to 1.37 in 2009. However, Indexmundi which takes its data from the CIA World Factbook has fertility much lower and actually declining in Japan. The latest data point from the CIA World Factbook reports an estimate of TFR in 2011 is 1.21. This is a pretty steep difference and I invite comments as to suggest the right number or at least the right trend.

(click on picture for better viewing)

All this is of course underlines Kinmont's point that we don't know the future and that economists have a proven track record for abysmal forecast performance. Still, we should get our concepts right at the offset. Long term projections in age structures are likely to be robust as they are a function of people already being born and while migration may change the course of ageing in any given country the fact that we are all ageing at one at the same time means that there are fewer migrants to go around. I would then claim that ageing does matter and that understanding how an economy such as Japan adapts to the ageing of its population remains one of the most vexing and important issues for social scientists and investors alike.

So when Kinmont implies that low fertility in Japan is a non-issue I have to strongly oppose. Just take a look at the chart above Kinmont himself uses. Fertility has been below replacement levels in Japan since 1970 and on current growth rates (assuming a constant growth rate of fertility which in itself is dubious to the extreme) fertility levels would reach replacement levels some time in 2030-40. So, that would be 60 years with below replacement fertility. Even if fertility in Japan (and again in most of the OECD) took a discrete jump to replacement levels it would do very little to change the outlook for ageing in the immediate future.

In claiming that demographics do not matter Chancellor are Kinmont are taking a very wide brush over the general recognition in the academic literature that our economic systems tend to hit a snag once fertility falls below a certain level (a TFR of 1.5). This is also called a fertility trap and what it means is that it becomes very difficult to escape negative population dynamics once they set in. I emphasize this since it highlights that we are not, as a friend of mine likes to point, simply shooting arrows into the void when we point to the importance of these issues. I recommend the following presentation by Wolfgang Lutz et al and the paper that goes with it or this old post at AFOE by Edward if you are still not convinced.

In terms of the postulated increase in Japanese fertility since the mid 2000 it is a positive development, but as is evident from the data this rebound is extremely uncertain. In addition, we need to know whether this is just an echo of the tempo effect (and thus how large the rebound is likely to be) or whether it reflects a real change in attitudes on quantity. I am open to contributions here but the only thing we can for certain is that ageing, in Japan and the rest of the OECD, will continue its march onwards. Here I also feel that Kinmont puts up a straw man when he invokes the idea of Japan's population going to zero;

The unrevealed assumption, then, behind the mathematics used to arrive at widely-used population estimates is that the Japanese population will drop to zero. One cannot help but suggest that the logic of demographic pessimism is circular.

I want to re-emphasize that the issue here is not predicting fertility and death rates but recognizing the effect that the current and past trends have on ageing today and tomorrow. Try the recent work by Wolfgang Lutz, Warren C. Sanderson, and Sergei Scherbov if you want to see the cutting edge here and while uncertainty is still a key variable ageing remains a tangible reality. The main question issue I would like to get across is then that the demographic transition manifests itself in a transition of ageing and that this essentially becomes our main unit of analysis.

Growth and Demographics, No Connection?

Kinmont and Chancellor argue that demographics are likely to be less important for growth over time as total factor productivity (TFP) growth tends to be the main driver of growth.

Japan could quite easily grow at a good rate, especially in per capita terms, for a high-income developed country even in the face of a falling population (or more precisely a falling working age population). All that is required is for TFP growth to accelerate back to the level of growth enjoyed by Japan prior to the bursting of the Bubble in 1989. TFP slowdown preceded the population peak. Variation in TFP performance not in labour input growth is likely to be larger than the negative effects of population change.

This is an important point and more importantly, Kinmont offers an argument to explain the declining labour input in Japan’s economy which links in with the fact that Japan has been stuck in deflation and at the zero lower bound for the best part of two decades (my emphasis).

Labour input has in fact fallen at an accelerating pace over the past 20 years. It is clear that the fall is principally a decline in man-hours. This cannot be simply a function of a decline in the working age population because that decline only began in 2000. Instead, its origins must lie in rising unemployment and under-employment. A persuasive new paper, The Paradox of Toil, by a researcher at the NY Fed [3] argues that a decline in labour input is a natural consequence of a deflationary economy with zero (or effectively zero) interest rates.

In short, the declining labor input in Japan is a function of deflation and being stuck at the zero lower bound. In addition, this Fed Researcher Kinmont refers to is Gauti Eggertson who studied under Krugman at Princeton and did most of his initial work on the liquidity trap and the zero lower bound. So, I would be careful getting in his way without a strong look at the argument.

I think however that we might be dealing with the problem of a missing link in the sense that demographics may be one of the primary sources of deflation and the liquidity trap in the first place. This is an argument that has been pushed in Japan’s case in the sense that it was a lack of pent up demand that held Japan back in the 1990s as well as deleveraging. Indeed, Japan may hold a cautionary tale on the effects of a balance sheet recession in an economy where fertility has been below the replacement level for an extended period. The Eurozone periphery (ex Ireland) who have even ceded monetary policy to Frankfurt are case studies to this theory I think.

I would also emphasize that as labour input declines so does, obviously, consumption (aggregate demand) input which again feeds into the the paradox of thrift in the closed economy (or perhaps even a realisation crisis?). In an open economy it leads to export dependency as domestic investment actvity responds to foreign demand as well as the excess income you earn from a positive net foreign asset position (if you are so lucky as to have one) becomes a crucial source of growth.

Another more fundamental point is that if the total factor productivity growth (TFP) is a residual what is actually hidden in this residual? Well, I had a wack at the whole argument a while ago from the perspective of the academic armchair.

Technology and productivity are famously assumed exogenous in the Neo-Classical tradition while New Growth theory as it was developed in the 1980s and 1990s emphasised the need to specifically account for the evolution of technology. Today, I would venture the claim that there is a consensus that productivity and technology is a function of what we could call, broadly, institutional quality which encompass almost anything imaginable from basic property rights to the level of entrepreneurship. Indeed, a large part of research is still devoted to pinning down exactly which determinants that are most important here both across countries and through time. Now, I would argue that, in the context of standard growth theory, this is where the scope for the study of the effect of population dynamics is largest. Thus I don’t think it is unreasonable to expect the level and evolution of productivity growth and technological development to be a function of the current population structure but also its velocity which is a function of e.g. migration (new inputs?), future working age size etc. Also, this is also where human capital and the evolution of technology is joined at the hip through the idea of innovative capacity and readiness.

Once we venture into the notion of endogenous growth theory and thus the attempt to directly explain the sources and components of total factor productivity growth there is growing evidence that age structure/demographics alongside a host of other variables are important. Try this one for a recent literature review, and for the general link between growth and demographics the list of contributions is long. You just need to read around a bit.

I would argue then that growth and prosperity of the modern capitalist welfare state is highly conditional on some form of demographic balance and Japan has long since moved beyond into unbalanced territory. Basically, Japan is stuck in a liquidity trap as well as a fertility trap. The latter works along the lines of depressing consumption demand and making it very difficult to maintain key economic structures such as e.g pension systems. In addition, ageing affect the growth path of an economy and leads to export dependency, this last point however which I concede is not yet an established fact in the literature.

What about stocks then?

We seem to have two intertwined arguments here. Firstly, the extent to which demographics may have an influence on growth it is irrelevant for the investor since you can't buy GDP growth anyway. Secondly, the evidence of a correlation between demographics and equity prices is weak and indeed, if anything, should be bullish for Japan (this last point is made by Kinmont).

Thus the FT summarized the latest findings of the London Business School team of Dimson, Marsh and Staunton, as published in the Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook, 2010. The LBS academics examined all the available data (83 markets), and concluded that “99 per cent of the changes in equity returns could be attributed to factors other than changes in GDP”. (...) Growth is not all that it is cracked up to be. This analysis underscores previous academic findings showing that growth

per se to be of only small importance to stocks.

It would be unwise to disagree with the gist of this point. Even if I can make a connection between demographics, growth and investor performance it is very likely that buying into such a story at too high a valuation will lead to poor returns. Buying at the right value is the most important aspect of any investment decision.

This however is not the same thing as saying that just as you make sure to "buy cheap" poor demographics, low growth etc are completely irrelevant. Rather, I think that the extent to which the modern investor needs to understand a decidedly more complex macro picture with lingering deflation, heightened risk of sovereign defaults and zero lower bounds the understanding of demographic dynamics is key. We are then again discussing the question of deflation and low interest rates in Japan;

The origin of Japan’s problems is falling valuation when compared with the rest of the world. When we note in addition that it is excesses of inflation or the arrival of deflation (that is, monetary phenomena reflecting policy errors) which tend to reduce market average valuations, we feel it safe to conclude that demography will have next to nothing to do with the longer-term return profile of the Japanese market either in nominal or real terms.

I feel this is a very dangerous claim to make because it assumes that the deflation dynamics of Japan and indeed the problems facing the Bank of Japan in reviving credit growth are unrelated to demographics. In addition there is the unintended consequence of BOJ having to monetize an ever greater amount of JGB issuance in the future which in itself becomes more paramount as Japan ages.

On the second point regarding a direct relationship between demographics and stock prices (asset prices in general if you will) I think Kinmont does better especially because he does not fall into the asset meltdown hypothesis trap. In short the asset meltdown hypothesis states, in a US context, that as the baby boomers retire they will dissave and thus need to sell off their financial assets to a market which cannot support the flow, because the generation in the working age years is smaller, and that this will lead to an "asset meltdown". Generalized, this is then the classic (and naive) nexus between life cycle economics and financial markets which postulate that dissaving into old age is rapid and imminent.

There are two problems here. Firstly, the empirical (and indeed theoretical literature) has found it very difficult to verify that dissaving occur among elderly cohorts to the extent postulated by the standard life cycle theory. Secondly, the relationship between asset prices and broad demographic aggregates appear weak. Results differ from country to country and most studies take place in a US and Anglo-Saxon setting which tend to bias the results further.

Kinmont does however point to a study by Geanakoplos, Magill and Quinzili [4] which show how the ratio of the 45-54 age group to the 25-34 age group is closely related to P/E ratios. As this ratio is set to increase in Japan, Kinmont ventures the idea that, if anything, perhaps you would want to buy Japan on the basis of demographics.

I have read the research by Geanakoplos et al and I find it intriguing, but my problem is that it does not control for the old age dependency ratio which suggests that the key ratio will be correlated with ageing in general. But I should be hesitant disregarding it on the basis of this hunch. I am preparing a large panel data set at the moment on demographics and stock prices with the aim to essentially rejuvenate a literature which seems too focused on the asset meltdown hypothesis noted above.

On a more general level, demographics and investment has been a core theme in the post crisis flow into emerging markets which, by and large, share the characteristics of being in the middle or at the end of their demographic dividend. Again, this does not nullify the importance of valuation and certainly, the recent soft patch notwithstanding, many emerging markets are still looking expensive.

Where goes the DIP then?

If you build your story up around the notion that investors buy value and not GDP growth you can easily come to the conclusion that demographics are irrelevant for the investor at large. This however would be a mistake.

I would be the first to wish for a return to a state of affairs in which investors needed only to look at valuation and firm fundamentals to make their decisions. Today however, you need to understand the macro backdrop and in order to do that you need a firm grip on how demographics affect macroeconomics. Pointing out that we are poor at predicting birth and death rates as well as pointing to weak evidence between growth and demographics do not cut it. We need not predict fertility and mortality but instead we need to understand the effects of ageing already present and there is plenty of evidence that demographics affect the growth rate and growth path of the economy.

I am more sympathetic to the strict relationship between stocks and demographics which is fickle and not well understood. Clearly, there is not presently any convincing model or framework which suggests how and why you might be able to buy sound demographics on a beta level. My main bet is that demographics should, at least, be used to qualify the notion of the global market portfolio and especially that demographics be used to re-balance such a portfolio over time.

In conclusion, Kinmont and Chancellor bring up some valid and good points in their attempt to brush away demographics as an important input variable to investment and macroeconomic analysis but you shouldn't be fooled. Just as was the case with the original DIP you accept this new version at your peril.

---

[1] - Franco Modigliani and Merton H Miller (1958) – The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance and the Theory of Investment, American Economic Review 48 (June 1958) pp. 261-297.

[2] - GMO White Paper - After Tohoku: Do Investors Face Another Lost Decade from Japan?, Edward Chancellor and Morgan Stanley Japan Strategy - The Irrelevance of “Demographics”?, Alexander Kinmont. I realise that I have lately been referring to sources and pieces of research which by nature of their origin (banks, research firms etc) are behind subscription walls. I am sorry, but I will make sure to produce relevant quotes so that my readers can follow the issues and arguments. I cannot upload full PDF versions of the reports for obvious reasons and I hope my readers will understand.

[3] - The Paradox of Toil, Gauti Eggertsson, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 433, February 2010

[4] - Demography and the Long-run Predictability of the Stock Market. John Geanakoplos, Michael Magill, and Martine Quinzili; August 2002, Revised: April 2004. Cowles Foundation Discussion Paper No. 1380