"Thailand has even gone the extra mile to explore additional land for rice production," James Adams, World Bank Vice President for East Asia Pacific

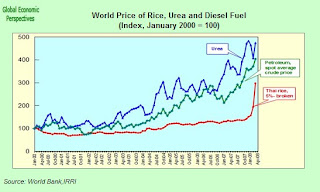

The above quote is a reference (of course), to the current global shortage of rice for international trading purposes and to the sudden spike in rice prices (see a much fuller explanation of the whole issue in this companion post). James Adams is simply highlighting one possible step that can be taken, if not towards a complete solution, then at least along the road to an amelioration of what is likely to become - in some of the world's poorer regions - a very acute crisis indeed. But the issue of rice prices (and indeed of the whole structural rise in food and energy prices) is a complex one, and a lot of seperate factors come into play. Land use is simply one of these.

In Thailand’s Than-En village, Phantipa Chongrak, 38 sold her last four-tonne, unprocessed harvest in January for $235 per tonne, half what rice is selling for now in her area. But Ms Phantipa, who owns 1.9 hectares of land, has now bet big on higher rice prices – renting an additional 5.6 hectares to cultivate an unusual out-of-season rice crop, an investment of about Bt150,000 ($4,730, €3,020, £2,380).

Hoping to profit from the soaring price levels, plenty of other Thai farmers have done the same, with Thai agricultural officials predicting an extra 1.6m tonne harvest in June. But that has left Ms Phantipa anxious about her expensive gamble. “I’m thinking and worried that in the next two months the price will be down,” she says.

Obviously the decision procedure facing farmers like Phantipa Chongrak is a complex one. To some extent they need to bet that the rise in prices is going to be more or less permanent (which it may well be) but they will almost certainly be doing this on the basis of very "imperfect information" since they do not have their disposal the sophistocated models and information which international economists can resort to (and god knows, we have a significant enough tendency to get things wrong).

It has been estimated that the price increases may lead Thai farmers to cultivate up to 16,000 hectares (39,520 acres) of previously idle land this year, and , in addition, many growers plan to plant an extra crop.

Rice growers and their families constitute a third of Thailand's 65 million population, and those who own their own land earn an average of 12,837 baht ($404) a month, compared with 33,088 for a Bangkok family, according to data from the National Statistics Office. Thai rice exports were up 36 percent from a year earlier in the first four months of this year, and the country may supply 45 percent of world exports in 2008, compared with 31 percent last year, according to the Commerce Ministry.

Before the shortage, Thailand estimated it would produce about 20 million metric tons of milled rice this year and export about 9.5 million metric tons. The additional cultivation that is now envisaged may increase output by 660,000 metric tons - enough, for example, to supply Mexico's annual imports.

But there are problems. Apart from the unpredicatability of future short term movements in prices, water is also an issue. Thai farmers normally plant in two crops: the main one around mid-year and the second near year's end. Now, they're planting at least three times, which means dipping into water typically saved for the dry season that starts in November. The Royal Irrigation Department said in April that reservoirs were at 64 percent of capacity, down from 71 percent a year earlier. It also warned against planting a third crop in two northern provinces, citing limited water reserves. Paddies have been guzzling 20 percent more water than normal so far this year, according to Theera Wongsamut, director general of the irrigation department.

And there is also growing indebtedness among Thai rice farmers. The state Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives expects lending to rise 25 percent to 250 billion baht this year on increased demand from rice planters, according to bank President Thiraphong Tangthirasunan. Farmers are borrowing the money to buy equipment like water pumps since they are planting more while the water supply is limited. They are also busily buying fertilizer, seed and pesticides, and trading-in buffaloes for mechanized plows.

So James Adams is right, many in Thailand are preparing to go that extra mile (and let's just hope for there sake that they don't need to "erect one bridge too many" to cover it).

Structural Issues in the Global Agricultural Labour Market

As I say the totality of issues which are being raised by the recent rise in food and energy costs constitute a very complex problem indeed, and in these posts I do not pretend to be able to address all of them. Indeed the question I am raising here is really a very simple one: there is no doubt that globally we have the land surface available to increase agricultural output substantially - even if we should be aware that presently unused land is unlikely to be of the same quality as the land which is being currently put to use (otherwise it is hard to see why it is not currently producing). We also have the technological resources to increase agricultural productivity in a way which enables us not only to feed the additional global population we are facing, but even to meet the needs presented by the rapid rise in living standards which is also taking place in the emerging economies.

We have both of these things (land, technology), but do we have the people we need to put them to work? Or better put - since obviously with those extra billions who are about to come on line across the planet we could hardly be said to be short of people - do we have the right people in the right places? That is to say, do we have the people where we want them, and with the levels of skill and education (you know, to use the technology effectively) that we need? Since if we don't we have what economists have traditionally called a "bottleneck problem", but this time we have it on an unprecedented (global) scale, a scale where the traditional economic remedies (labour market mobility and flexibility) tend to meet with a very high level of cultural resistance.

To take the most simple example, when we start talking about recovering currently unused agricultural land (that extra mile, remember), we might like to stop to think why it stopped being used in the first place. One obvious reason is that it wasn't sufficiently productive at the then prevailing prices, and this will often be true. But another reason would be that growing urbanisation and declining rural populations have simply meant that some land became fallow for demographic reasons (namely that there were not sufficient people willing to stay and work it, at least at the wages which were then being offered), which brings us straight back to my principal point - where and how are we going to find and persuade the people who could work the land to do so. Even the best designed plans - which always look ever so easy and attracive on paper - all too often come to founder on harsh and complex "on the ground" (no pun intended) realities. And if the solution here passes through raising rural wages and rural living standards, then remember that those of us who live in highly urbanised and developed societies may well notice this, in the form of higher prices, continuing inflation in food and energy, and indeed very possibly in a sustained period of what economists like to call "stagfaltion". That is, what we are talking about here isn't exactly small beer.

Migrant Dependence in Thailand

Turning now to a specific example, in the Thai case this whole "where does the labour come from" question is no idle one since fertility - including rural fertility - is now well below replacement level and still falling, and every year less and less young Thais are available to enter the labour market. So basically if the Thais want to work extra land they will need to find the human resources with which to do it.

One option, evidently, is immigration, and the tragic death by suffocation of 54 migrant workers from Myanmar who were being transported into Southern Thailand in an enclosed container truck earlier this month certainly drew the attention of the world's press to existence of this phenomenon in Thailand and to the level of dependence which the current expansion in the Thai economy now has on imported migrant labour. So it isn't only capital which is flowing strongly into Thailand at this point (the astute reader will recall that in fact the Thaksin government actually fell shortly after taking the decision to try to stop too much capital entering the country), labour is also streaming in to allow it to be effectively put to work.

The migrants who died were following a route that tens of thousands of others from Myanmar had taken before them. They are drawn to Thailand to work in jobs described by locals as "dirty and dangerous" - the fisheries industry, construction sector and on rubber and palm oil plantations.

In fact migrant Myanmar labour has long formed a significant part of the workforce who make possible the construction of all those hotels and holiday complexes that now dot the beaches of Phang-nga and Phuket, the mainstays of Thailand's vibrant tourist industry. In the fisheries sector, the men are employed on the boats that go out to sea, while the women work in factories to process the catch.

True, the numbers are not at this point large by Western European and US standards, but they are strategically deployed across the economy. In 2007, Thai labor officials and NGOs estimated that there were some 2 million migrant workers in Thailand, 75% of whom came from Myanmar, while the rest came from Cambodia and Laos. Only 500,000 of these however were registered with the Thai Labor Department.

According to a recent report "The Contribution of Migrant Workers to Thailand" (Main finings online here) prepared for the International Labour Organization by Philip Martin of the University of California (Davis) total migrants in Thailand rose from about 700,000 in 1995 to 850,000 in 2000 and to 1,773,349 in 2005. They constituted 2.2 per cent of the labour force in 1995, 2.5 per cent in 2000, and 5 per cent in 2005.

In 1995 some 42 per cent of the migrants were registered. In 2000 this was up to 67 per cent, but by 2006 it had fallen back again to 26 per cent, with these large fluctuations in the ratios undoubtedly reflecting ambivalence on the part of the Thai authorities to the whole situation. They need the workers, but they don't really want them. How resonant this is of so many situations in so many other countries. Perhaps those who imagine that land can simply be rolled online as we need it (right along a nice simple neo classical production function) might like to think a little more deeply about these kind of issues.

In terms of activities involved, the ILO found that in 2005 the migrants they were able to identify were distributed roughly as follows : 720,000 in agriculture, 720,000 in industry, and 360,000 in services.

Philip Martin calculated - making the assumption that the migrants were as productive as their fellow Thai workers in each of the sectors where they work - that the total migrant contribution to output would be in the order of $11 billion (or about 6.2 per cent of Thailand’s GDP). Assuming they were somewhat less productive (say only 75% of Thai worker output) then their contribution would still be in the order of $8 billion (or 5 per cent of GDP). So we could estimate that migrants in Thailand now contribute anywhere from 7 to 10 per cent of the value added in industry, and 4 to 5 per cent of the value added in agriculture.

Really the picture we are seeing in one country after another across the globe is strikingly similar from this point of view. As countries fall below replacement fertility they increasingly come to depend on migrant labour to work in areas like agriculture, construction, low skilled industry and domestic work. Yet in Thailand, as in many equivalent western countries the new and much needed workers are often far from popular.

Thailand returned to civilian rule in January 2008, with Samak Sundaravej of the People Power Party replacing deposed prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra. The PPP campaigned on a populist platform aimed at reducing rural poverty, and said it would use its first six months in office to revive the economy before tackling controversial issues, including migration.

The military government that ruled between September 2006 and January 2007 had taken a hard line against migrants from neighboring countries, supporting five southern governors who banned migrants from talking on cell phones, riding motorbikes, or leaving their Thai housing between 8pm and 6am. However, faced with the inevitable it did prove to be just as flexible as governments elswhere at the end of the day and finally approved a plan to allow migrants who failed to re-register in 2007 to pay a fine (3,800 baht, $120) and register for two-year work and identity cards during January-February 2008.

As I have said most migrants in Thailand are employed in low paid unskilled jobs in construction, manufacturing, agriculture, fisheries and domestic service in northwestern and southern provinces. Relatively few jobs held by migrants are attractive to Thais and few migrants work in the areas of highest unemployment in Thailand's northeast. The apparent magnitude of migrants' contribution to Thai GDP and their sectoral concentration suggests that they will continue to contribute substantially to the country's economic development for the foreseeable future.

The Vietnamese Case

But turning now from a country which is below replacement fertility and importing migrants, to one which is below replacement and exporting them, let's examine the case of another of the world's leading rice exporters - Vietnam - which is in fact the third exporter globally after Thailand and India. As can been seen in the chart below, Vietnam has enjoyed very rapid economic growth in recent years, especially when measured in US dollar terms, and this economic growth has both raised living standards and expectations, and reduced productive land available for rice cultivation.

As I have been trying to argue, the issue of rice prices (and indeed of the whole structural rise in food and energy prices) is a complex one, and a lot of seperate factors come into play. Land use is simply one of these: Vietnam’s total paddy acreage has dropped from 4.3m hectares to 4m hectares in recent years, and part of the reason for this has been increasing pressure on land use from other areas like industrial development and housing. Of course, raising output is not incompatible with using less land, providing productivity rises fast enough, but this (as we will see later) is not always as easy as it sounds on paper. A second factor which is also important is inflation - and again as we will see, Vietnam is now suffering from a fierce bout of inflation - since rapid rises in the prices of some basic commodities can lead to hoarding in the expectation of future price increases, and the only way to halt this is to convince people that prices will stabilise, something which in the present climate is very hard to do indeed. Basically a combination of rapidly rising living standards and an increase in inventories for "hoarding" purposes can provide us with a large part of the explanation for why it is that despite the fact that Vietnam has now ceased to export rice the queues to be found in Ho Chi Minh city are currently longer than anything which has been seen since the height of the communist era.

But things are not, as we have been seeing (in, for example, this accompanying post on the roots of the problem) as simple as we - or classical economic theory - might like them to be, since many things are interconnected here, and in fact far from being able to simply breeze that extra mile that James Adams is rooting so hard for, Vietnamese farmers are currently losing thousands of dollars every year as a result of manpower and machinery shortages when it comes to harvesting the rice they would evidently like to grow.

Provinces in the Mekong Delta region continue to face a lack of workers to harvest crops.

At least this is the situation described in a recent survey carried out by Can Tho University, and the problem has now started to become an acute one since - owing to Vietnam's spectacular recent growth (see above chart) - potential young farmerworkers are leaving in droves for urban centres, industrial parks, export processing zones or points farther afield (external migration), in search of jobs which offer better pay, and given the collapse in Vietnamese fertility which has taken place since the late 1980s, there are now, in a fashion which is eerily similar to the pattern we have already been noting in China, fewer and fewer young workers about to enter the Vietnamese rural labour market, creating a potentially huge long term labour gap in areas like the Cuu Long (Mekong) Delta (Viet Nam’s biggest breadbasket).

For Vietnamese farmers, the sharp rise in rice prices comes amid rapid change in the rural landscape. Vietnamese rice farmers today are far more productive, and prosperous, than they were during the ill-fated, and long abandoned, drive to collectivise agriculture. But in the new drive for nationalisation, much prime paddy land is being converted to factories and housing.

According to Hanoi’s Institute of Policy and Strategy for Agriculture and Rural Development, Vietnam’s total paddy acreage has dropped from 4.3m hectares to 4m hectares in recent years, which has raised concerns about the country’s long-term food security. “We are warning against diverting [rice] paddy land to other uses,” says Duong Ngoc Thi, a senior official at the institute.

Of course increased investment in improved technology would help - a combine harvester operated by three people has the manpower equivalent of 100 farmers - but apart from finding the money to make this work, the techno-fix is not that simple since Vietnamese paddy fields are wet and muddy compared with the waterless fields which serve for other crops, and this makes it much harder for foreign-made, modern machines to work well in them.

Nonetheless an increase in investment would undoubtedly help the Vietnamese rice industry avoid so much of its potential crop each year, according to Nguyen Van Chien, an official from the Vietnamese Ministry of Agriculture, and agricultural mechanisation could help enhance the quality as well as the quantity of Vietnamese rice, boosting the country’s competitiveness for rice exports with its chief rival, Thailand. At present, Vietnamese rice sells for around $20 less per tonne than Thai rice.

Of course, it is important to bear in mind that despite the dramatic drop in fertility Vietnam's population is still rising fast. This is the so-called "momentum problem", since the last cohorts from the high fertility era are very numerous, and thus when they reach childbearing age will tend to produce a large number of children, even if the number each individual woman has is a lot less than previously. In addition we need to add-in the impact of increased life expectancy as rising living standards improve the general health of the population. So Vietnam's population is both increasing, and ageing rapidly, and this latter issue will undoubtedly have significant consequences later on.

It isn't only in rural Vietnam, however, that labour shortages are now appearing. The Ho Chi Minh City Construction Association has forecast that this year the city will face a labour shortage in the construction industry since the number of building projects awaiting execution has doubled. In a recent report they noted that the shortage problem got significantly worse in the post-Tet holiday period, since (and in an example which follows a pattern we have already seen in China) many young workers did not return to their jobs after the holiday. Most construction companies have been busily raising wages in an attempt to entice more people yet the shortage persists. Nguyen Huu Quang, deputy director of the NBH Building Service Ltd. Co, is quoted as saying that construction companies in HCM City were in danger of losing a significant part of their human resources.

As I mentioned, this failure of people to return after the Tet holiday is surprisingly reminiscent of the situation as reported in China after the end of the recent winter holdiday. The Economist - in an article entitled Where is Everybody - reported that the vast annual migration of around 20m people that has been fuelling the manufacturing boom in southern China over the past two decades is now rapidly diminishing.

The Guangdong Labour Ministry is reporting that 11% of the workers did not return after the January holiday period, and independent estimates put the number as high as 30%. Whatever the exact details, many factories are reeling. Wages were already rising (according to government figures by around 20% y-o-y) now they will surely go up further. Meanwhile, revenues are falling due to slowing demand from America and a reduction, following pressure from other countries, in China's complex system of export subsidies.

According to HCM association’s figures, construction companies in HCM City currently can supply more than 42,000 skilled masons, a number which is far below the real demand for workers, which is thought to be somewhere in the region of 100,000. In a trend which has been evident in other countries (like Eastern Europe) skilled construction worers have either transferred to other provinces (or gone abroad) or returned to their hometowns where better infrastructure now exists and a rapid rise in the construction of industrial parks and export processing zones is producing plenty of work.

And what is the result of these growing labour shortages? As we have been seeing elsewhere (and again the East European comparison is instructive) the outcome is virtually inevitable: rapidly rising wages and accelerating inflation. Vietnamese consumer prices rose 21.4 percent in April, the fastest pace since at least 1992 and the IMF are now forecasting annual inflation of 16% for the whole of 2008 in Vietnam.

These growing labour shortages, which can to some extent be anticipated in any economy which is growing rapidly, are exacerbated in Vietnam by the fact that many potential workers - in a way which is similar to the situation which is to be found in Poland or Romania - now work abroad, whether as temporary or permanent migrant labour. There is, however, one important difference between Vietnam and Eastern Europe in this regard in that Vietnam has an active policy of encouraging what they call "labour Export", indeed the Ministry of Labour has a whole department which is dedicated to the topic. The reason that this policy is persued is not hard to imagine. It is summed up in one single word: remittances. For 2006 the World Bank estimates that migrant workers sent home to Vietnam roughly $4.8 billion, or 7.5% of GDP. Of course such a sizeable flow of money has an impact in its own right on the Viet Nam economy, creating in its wake more consumer demand, and with this more demand for construction, and with this more demand for construction workers who, as a result of one of those many anomalous circularities we are able to identify here, happen all to be often to be working out of the country and are doubtless to be found among those actively sending money home. When you stop and think about it it isn't hard to see where all that inflation comes from here.

As I say, it is not simply a question that people from Viet Nam want to go to work abroad, the Vienamese government is actively encouraging the process. As a result the number of foreign destinations has been expanding significantly. There are now more than 40 countries to which Viet Nam "exports" labour, compared with 15 in 1995. The Vietnamese labour market generated about 1.68 million new jobs in 2007 according to the Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs. About 1.6 million of these new jobs were generated inside Viet Nam, but about 85,000 were jobs abroad, and these brought the total number of Vietnamese guest workers and experts officially working abroad to over 400,000 in 2007. And the Labour Ministry is working on further expanding the business, since it has plans to raise the rate of "exported labour" at an annual additional rate of 40,000 to 50,000 (to around 130,000 annually) by the time we get to 2010, an increase of 65 five per cent over a five-year period.

Job seekers at a recent employment exhibition held in Ha Noi. Obviously given the wage differentials which exist people are eager to leave, but should the Viet Nam government be actively promoting the process? In the short term it eases pressure on the labour market, but at what price in the longer term?

One destination which is proving increasingly popular is South Korea, and the Vietnamese Ministry of Labour recently proudly announced that Korean companies would like to recruit 15,000 Vietnamese guest workers in 2008, 27 per cent more than last year. In addition the Korean Government has decided to allow 1,000 migrant Vietnamese labourers who had originally registered for agriculture work to transfer to construction, which is itself suffering from a shortage of workers, according Vu Minh Xuyen, vice director of the External Labor Center of the Vietnamese Ministry of Labour.

Xuyen said the workers will have to take an exam testing their understanding of the Korean language. The exam can be taken in May or October. Those living in remote areas and poor rural areas will be given priority.

Workers seeking South Korea employment learn Korean at a job service centre in the Central Highlands in Gia Lai Province. Korean company demand for Vietnamese guest workers this year is 27 per cent up against last year.

Of course South Korea is facing its own low fertility driven labour market issues. According to U.N. statistics, the fertility rate per women has fallen from 5.4 in 1995 to 1.5 in 2005 with the estimate for 2050 being 2.1. The population in the age group of 15-59 it is estimated to fall from 68.2 percent in 2000 to 50.4 percent in 2050, whereas the share of 60 plus population is to rise from 11 percent in 2000 to 33.4 percent in the same time span.

Recent statistics show that South Korea's birth rate fell to its lowest (in 2005). The projected (Health-Welfare Ministry forecast) fall in population from the present level of 48 million to 40 million will occur over next 45 years. The ageing index (U.N. statistics) is projected to grow from 52.7 in 2000 to 150.7 in 2025.

In a recent Korea National Statistical Office report, this index is forecast to reach 100.7 in 2016, almost doubling from 55.1 in July 2007, further projected to as high as 213.8 by 2030. This will put a tremendous financial burden on the working-age population (those aged 15 to 64), to support those elderly citizens, while the ratio of the working-age population to senior citizens is predicted to drop to as low as 2.7 per one elderly by 2030, as compared to the present level of 7.3 to 1.

So naturally Korea is going to increasingly need to import labour, and my only question is: does it make sense to import this labour from a country like Vietnam which itself is also going to be having problems over a fairly limited time horizon?

The point is economic growth of the kind Vietnam would like to have is very employment intensive. At the end of 2007, there were more than 45.6 million Vietnamese employed nationwide, an increase of 2.31 per cent over 2006, and the Ministry of Labour plans to generate a further eight million new jobs by 2010. This objective was recently announced by Dam Huu Dac, deputy minister in the department, who said it was part of a National Target Programme on Job Generation. "Each year, 1.5 to 1.6 million new jobs are being generated and a total of 49.5 million workers are expected to be employed by 2010." he said. And this is just it, right now Vietnam has a massive problem of job creation quite simply because the number of people of working age has been expanding rapidly, but soon, following that sudden turn downwards in the 15 to 19 age group curve, the problem will be inverted, and having constructed an economiy which needs and extra 1.6 million workers a year to keep moving the issue will be one of just where those workers are going to come from?

About 1.6 million seek to enter the Vietnamese labour market every year. Meanwhile, the nation’s population is growing by more than a million annually.

The question I am asking is really one about our whole perception of the ongoing demographic transition. Does it really make sense for a country with such low fertility as Viet Nam now has, and where labour shortages in rural areas and key sectors like construction are already being observed, to be so enthusiastically exporting - in a way which is very reminiscent of Eastern Europe - its future labour force? As I say, the issue here is as much one of changing how we see the situation as anything else, and getting it across to those responsible for making economic policy that "cutting your nose of to spite your face" may work in the short term, but in the longer term we are only building up problems, and big ones.

The Czech Connection

The story I am telling here is one of a web with many loose threads. And I wouldn't want to give the impression that I am arguing against labour mobility, far from it. I think that immigration from high fertility countries to lower fertility ones makes a lot of sense. What I am questioning is the movement of population from low fertility societies to higher fertility ones (from Poland and Latvia for example to the UK and Ireland, or from Ukraine to virtually anywere), and I am also questioning the advisability of countries which are attempting to grow rapidly while having falling and below replacement fertility actively encouraging and stimulating out-migration. At best this is simply moving the deckchairs round, and at worst it is robbing Peter to pay Paul when Peter is already out of money.

The strangeness and lack of apparent rationality in all of this is perhaps nowhere better illustrated by the close and growing connection between the Czech and the Vietnamese labour markets. The Czech Republic's economy is growing rapidly - around 6% to 7% per annum -and unemployment is amongst the lowest in the European Union. As a result the Czech Republic is now itself growing very short of labour (only 3 years after watching a stream of its own young people leave for work in the UK and elsewhere), since after 20 years of very low fertility (1.2-1.3 TFR range) there are now fewer and fewer young people coming forward into the labour market, and so, of course, the Czech Republic is busy out and about looking for migrants to fill the gap.

Initially they turned to their immediate neighbours, and indeed the largest group of foreign migrants with rights to work in the Czech Republic comes from Slovakia. At the end of last year, there were 101,233 Slovakians legally working in the country. Ukranians are the second most numerous group with 61,592 working in the Czech Republic as of last year. But there are problems here since both of these countries (and indeed all the other ones in the region) have very low fertility too, so they soon notice any drain on their labour resources, and this is then simply displaces a problem from one place to another and is not a long term solution.

As a result the Czech government is now looking further afield - much further in fact - since the number of Mongolian and Vietnamese workers working in the Czech Republic has been increasing rapidly. In 2007 there were 6,897 Mongolians working legally in the CR (up from 2814 in 2006) and 5,4425 Vietnamese (up from 692 in 2006). The numbers of Vietnamese present in the country is undoubtedly much larger, and according to the Czech police, there are almost 51,000 Vietnamese holding long-term or permanent residence permits for the CR, many of these associated with temporary student visas. Demand from people inside Vietnam is also way up, and the Czech embassy in Hanoi had to close its doors to visa applicants temporarily in March to reorganise itself in order to cope with the influx.

So you plug one gap to create another, and where I ask, is the method in all our madness here?

In this post I have not presented solutions, rather I have attempted to identify problems, problems which need to be addressed. But in order to adequately start to address the problem we need first to recognise that it exits. Basically I feel that far too many people - and especially at the institutional level - are still effectively in denial that the problem exists, and is important. What I would like to ask is when is someone (someone with some clout I mean) finally going to start taking seriously the idea that emerging economy countries like Vietnam need to try and do something about their fertility situation (and that something will undoubtedly involve dedicating resources to the issue) before they get stuck - like South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong before them - down on that very bottom rung?