Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko said last week that he had agreed to let Libya grow wheat on 100,000 hectares of land in the Ukraine. In exchange, Libya promised to include the former Soviet republic in construction and gas deals.

"

For the first time, it's been clear that we are consuming more rice than we are producing globally," said Robert Zeigler, head of the Philippines-based International Rice Research Institute, blaming population and economic growth."That is eventually unsustainable....People felt the global food crisis was solved," Zeigler recalled, referring to technology breakthroughs that boosted yields in the 1970s and 1980s, "and it really fell off the agenda of funding agencies."

With so many interesting debates going on the Demography Matters blog at the present time I find it hard to pull myself away, but I couldn't help getting drawn into the implications of the points raised by this article in the Financial Times about how the global pressure on food supplies and the rapid increase in prices is now leading to an equally rapid increase in the price of farmland in one country after another. And then, thinking about a country like Ukraine - with a declining population, rapidly falling unemployment, and growing labour shortages - I couldn't help scratching my head and asking myself, but just where are they going to get the labour force from to work all this extra land they want to cultivate?

But lets get back to land prices for a moment. According to the Financial Times with prices of commercial and residential property now falling in many developed economies, investors are begining to find themselves faced by a rather tricky problem set: they can either stick all those millions (or billions) which they no longer feel happy to place in first world property into a novel value store like food (and start for example hoarding rice, or buying soy futures) or they can turn their attention towards a more traditional and well established asset: farmland. Long seen as a declining sector, agriculture has just received an enormous fillip as global demand for food has skyrocketed. As a result, the value of agricultural holdings across the European Union has been rising to record levels.

In the UK prices for farmland have risen by 40 per cent over the last year alone, and there is apparently plenty of room for prices rises across the entire European continent. In Lithuania - to take just one example - a hectare of agricultural land was estimated to cost €734 ($1,167) in 2006 compared to €164,340 in Luxembourg (which was Europe's most expensive country at the time). In Poland average prices for farmland are estimated to have risen by 60 per cent between 2003 and 2006. In neighbouring Ukraine – not an EU member – prices for the best land are forecast to double this year from the 2007 value of $3,500 per hectare as one investment fund after another piles in (you know, all those pensions people will be looking to receive later). Even Serbia, another non-EU country, has seen a steep increase. Real estate analysts estimate arable land prices in Serbia’s agriculturally rich northern region, Vojvodina, at roughly €7,000-€8,000 per hectare this year, up sharply from €5,000 last year.

Even in distant Afghanistan the rise in the value of conventional farming is being noted, since opium crop is forecast to shrink by as much as half this year after 2007’s record harvest, according to counter-narcotics officials in Kabul, as evidence grows that poppy farmers are switching to legal crops, attracted by the rising food prices.

All of this raises a number of very interesting questions, not least of them being why it is all happening now (number one), and where many of these countries who have surplus land to offer- but have had congenitally low fertility for longer than I now care to remember, and have been busying temselves over the last few tears exporting what scarce labour resources they have to Western Europe or Russia (Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine, Poland, Slovakia, Romania, Bulgaria etc) - are going to find the labour force they would need to work the extra land (number two).

Why The Price Rise Now?

Well on the first point, I really can't do better than direct your attention to another very interesting article in the Financial Times, this time one from Martin Wolf, entitled "A turning point in managing the world’s economy". Wolfe's main point for our present purposes is this one:

"As the latest World Economic Outlook from the International Monetary Fund remarks, “the world economy has entered new and precarious territory”. What are perhaps most remarkable are the contrasts between booming commodity prices and credit-market collapses and between buoyant growth in emerging economies and incipient recession in the US. So where are we? How did we get here? And what should we be doing?"The point to notice here is that it is not just investment funds who are busy adapting their behaviour since we all have a rather novel problem set on our hands, as the credit crunch wends it way forward and property markets drift (at best) into stagnation in one OECD economy after another, commodity prices are rocketing, and the best bet at this point is that the developed world is heading towards a protracted bout of stagflation (where central banks are constrained to operate a tight monetary policy, keep credit on a tight rein and basically restrain growth to contain inflation), while emerging market economy after emerging market economy (of course it is not quite as simple as this) seems to be revving up on the development ramp prior to launching into "we got lift-off" mode.

The April 2008 IMF World Economic Outlook estimates that the US economy may shrink by 0.7 per cent between the fourth quarter of 2007 and the fourth quarter of 2008, and eurozone growth is expected to fall to some 0.9 per cent or so this year, yet while the most important high-income economies stumble (even where they do not actually fall), the picture in the majority of emerging economies is for only modestly diminished growth, with rates of 7.5 per cent being anticipated for emerging Asia ( with China on 9.3 per cent and India on 7.9 per cent); 6.3 per cent for Africa; and 4.4 per cent in the western hemisphere. These latter are certainly not growth rates to be sneezed at.

But what we have going on here is not only a growth rate differential, it is also a massive currency re-alignment. The consequential rapid and dramatic rise in dollar GDP values (produced by the combination of strong growth and the declining dollar) means that convergence in global living standards - at least in the cases of those economies who are experiencing the strongest acceleartion - is now happening much more quickly than anyone could have - even in their wildest moments - dreamed back in the 1990s. All of this is very well illustrated by the case of Turkey, as can be seen in the chart below.

According to Wolf:

Emerging economies have been the engines of growth over the past five years: China accounted for a quarter; Brazil, India and Russia for almost another quarter; and all emerging and developing countries together for about two-thirds (measured at PPP exchange rates) of world growth. Furthermore, notes the WEO, these economies “account for more than 90 per cent of the rise in consumption of oil products and metals and 80 per cent of the rise in consumption of grains since 2002” (with scandalously wasteful biofuels programmes contributing most of the remainder).

This situation can be observed quite clearly in the two charts which follow, which are based on calculations I made last autumn from data available in the IMF October 2007 World Economic Outlook database. Now, as can be seen in the first chart the weight of the US economy in the entire global economy has been declining since 2001 (and that of Japan since the early 1990s). At the same time - and again particularly since 2001 - the weight of the so- called BRIC economies (Brazil, Russia, China and India) has been rising steadily.

This is just one example - and a very basic one at that - of why Claus Vistesen and I consider that demographics is so important, since it is precisely the population volume of the BRIC (and other similar) countries and the fact that they start their development process from such a very low base ( ie there is such huge "catch-up" potential since they were allowed to become so comparatively poor, for whatever reason) that makes this transformation so significant.

Again, if we come to look at shares in world GDP growth we can see the steadily rising importance of these BRIC economies in recent years and the significantly weaker role of "home grown" US growth. In 1999 the US economy represented 30.91% of world GDP, and in 2007 this percentage will be down to 22.4% (on my calculations based on the forceast made by the IMF in October 2007). In 200 the US economy accounted for a staggering 40.71% of global growth, and by 2007 this share is expected to be down to 6.43%.

But most of the data I present above predate the financial market turmoil of August 2007. In fact what has been happening post August 2007 is really fascinating and actually quite unique, since following the breakdown we have seen in some of the world's leading wholesale money markets - and in particular in the securitised-mortgage-paper based ones - the credit system in all the G6 economies is steadily slowing - and all the world's major developed economies are gradually entering recession. All the major developed economies, but not, of course, the newly developing ones, as I am indicating.

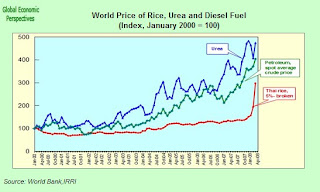

This state of affairs may well now become a relatively drawn-out affair since the structural rise in food, energy and commodity prices that is being produced by such a dramatic rise in living standards in the world's most populous countries means that we are likely to have continuing high structurally driven inflation. Some illustration of the problem can be seen in the chart below, which compares the relative price movements of diesel oil, Thai raice and urea. Urea is widely used as a nitrogen-release fertilizer, and over 90% of global urea production is destined for use as a fertilizer. Urea has the highest nitrogen content of all solid nitrogenous fertilizers in common use (46.4%), and consequently it is very effective since it has the lowest transportation costs per unit of nitrogen nutrient. Basically urea is commercially produced from two raw materials, ammonia, and carbon dioxide. Large quantities of carbon dioxide are produced during the manufacture of ammonia from coal or from hydrocarbons such as natural gas and petroleum-derived raw materials. So yes, you got it, the cost of urea is intimately connected with the cost of other major energy products - like coal and petroleum (as can be seen in the chart) - and this means that price of food is naturally propelled upwards by rising energy costs, whether or not we have the added complication of diverting agricultural land for the production of biofuels. If you don't produce the biofuels then the cost of petroluem products is going to be up, and this only pushes food products up by the indirect route. There is, unfortunately, no simple win-win strategy available here.

(please click over image for better viewing)

And to the rapid growth in GDP in the BRIC economies you need to add the longer term relative downward drift in the value of G6 currencies vis a vis emerging economy ones (the euro has still to feel the force of this, since recently it has simply risen and risen against the dollar, but I think the change will come, while the dollar case is already clear enough) - and the rise in the dollar value of the Turkish Lira, the Brazilian Real and the Indian Rupee (to mention but three of the more prominent cases) has been pretty spectacular since the start of 2007. What this effectively means is that in the OECD world we are now - more than likely - in for a protracted dose of stagflation, as central banks on the one hand are constrained from too much monetary easing by inflation concerns, while the credit crunch on the other seems to imply that cheap mortgage and personal finance is unlikely to become so widely and freely available as it was, whatever the base interest rates set by the central banks.

Yet unlike previous recessionary occasions (arguably ALL such previous occasions in living memory) funds are not coming running home to the G6 economies for safe cover during the current downturn. Instead they are in a kind of headlong flight towards the emerging ones: hence the steady fall in the dollar, and the rise in currencies like the Turkish lira, the Brazilian real or the Indian rupee. In these countries it is literally raining money (saving good old Ben the trouble of having to get his helicopter out). We could take the Indian case as a clear example here.India's foreign exchange reserves (which are a reasonably proxy for the rate of capital inflows) rose $2.7 billion to touch $311.9 billion during the week ended April 4, and this is a rise of some 50% on the level of $204 billion which existed in May 2007.

At the same time, and despite having fallen back somewhat recently, India's rupee is up substantially against the dollar, perhaps by 12% across 2007 as a whole.

What this really means to me is that the damn has finally burst - and that the huge accumulation of population at one pole of the planet and of wealth at the other is now in the process of unwinding itself - and really there is no turning back. Country after country is now hitting the development high road and this will not only have an impact on the rate of global population growth (slowing it markedly), global fertility (ditto) and global ageing (in this case we are likely to see an acceleration, as improving health increases life expectancy, while declining fertility reduces the size of the younger cohorts), it will also put enormous short term pressure on the supply of global resources, and it is on this issue that I really want to focus here.

The picture is that not only is population growing rapidly in some developing countries (foreseen), but both population and per capita living standards are growing (not foreseen) - and indeed these living standards are rising so fast that the gap between some of the leading countries and the developed economies is closing rapidly. This latter - unforeseen- effect is the principal reason we are seeing such acute pressure on the global supply of agricultural products.

One of the obvious reasons for such a sharp rise in demand for agricultural products is that food consumption forms a much greater part of the extra income earned in a poor country than it does in a rich one. As a rough and ready rule, the poorer the country the greater the share of every extra dollar earned which will be spent on food.

The poorest of the world’s poor are the 1.1 billion people with income of less than a dollar a day. Around 700 million—almost two-thirds—of these people live in rice-growing countries of Asia. Rice, the dominant staple in Asia, accounts for more than 40% of the calorie consumption of most Asians. Poor people spend as much as 30–40% of their income on rice alone. Ensuring sufficient supplies of rice that is affordable for the poor is thus crucial to poverty reduction. Given this, the current sharp increase in rice price is a major cause for concern.

International Rice Reasearch Institute

To take the example of Russia, Russia's very rapid economic growth since the turn of the century is producing an equally rapid rise in incomes and living standards. According to the Russian Statistics Office Rosstat, average real wage and disposable income increased by 16.2 and 12.9 percent, respectively during the first nine months of last year, and increases of this order, when coupled with currency changes, produce a very sharp rise in purchasing power, as can be seen in the chart below.

The consequence of rapid growth in a tightly constrained labour market like the Russian one isn't hard to predict: rampant inflation. In fact Russian consumer price inflation accelerated in March to hit an annual rate of 13.4% (Bank of Russia data), up from 12.7% in February, and led by bread, vegetables and other food costs. Prices rose 1.2 percent from February. Russian prices have already risen by an icredibly 4.8 percent in the first three months of this year alone (January to March).

And if we come to look for a moment at the components of Russian inflation (see charts below) we will find two of our old friends out there in the forefront - food and construction. In fact in the first 10 months of 2007 the rate of increase in construction costs was some 15% (as compared to only 9% during the equivalent period of 2006). And if we look at the chart for Russian CPI weightings (see below, - and note by way of comarison that in China and Turkey, food related products also constitute around 25% of the CPI basket).

And again here Russia is a nice example of the extent of this problem, since Russia's manpower shortages (see this post) mean that supply in the agriculture sector is now pretty constrained, while technological improvement if investment totals are anything to go by is not notably accelerating. Investment in transport and communication constituted 23.31% of total investment in Russia the first half of 2007, investment in real estate constituted 12%, and investment in agriculture constituted only 4.7% of the investment total.

In terms of FDI the situation seems to be even worse, since FDI in Russian agriculture only constituted 0.7% of total FDI during the same period (World bank data). As a result of all this neglect it should come as no surprise to find that labour productivity in Russian agriculture only grew by 4.4% per annum over the 1999 - 2004 period (the lowest by a long way for any sector, World Bank calculations), and thus starved of its workforce, and lacking the necessary capital investment to compensate, Russian agriculture is bound to struggle to meet the needs of an ever more affluent urban population. The result of course is that Russian inflation is now spiralling upwards almost out of control.

Richard Ferguson, an analyst at Nomura Holdings, argued recently in the Financial Times that Russia could raise its grain production fourfold by better crop management and returning fallow land to cultivation. Russia now has some 40 million hectares (99 million acres) of land lying fallow, equal to 50 percent of the area currently being cultivated, according to Ferguson. He argues that better management and more farming could increase Russia's production of cereal crops to 300 million tons a year, compared with 75 million tons now.

The argument looks very attractive on the surface. All too attractive perhaps? It doesn't really address the long term issues about why the land is fallow in the first place, and it certainly doesn't explain where the manpower will come from to fuel the output. Russia's working age population,rember, peaked in 2003 and is now steadily declining, and will, of course, continue to do so as far ahead as the eye can see. So you can't at one and the same time open brand new car factories in St Petersburg (etc) and put 40 million hectares of fallow land back into production, the human resources simply aren't there to do this.

Unless, of course, you import labour, which Russia is currently doing as a rate of around 1 million net new migrants a year (a precise figure for migrants arriving and settling in Russia is very hard to come by, since so many of the migrants - several million - are short term seasonal workers).

But it isn't only the total supply of labour which constitutes a difficulty, the distribution is also highly problematic, since Russia's labor resources tend to be highly concentrated in the centre of the country in a way which is starting to produce a serious nationwide imbalance. The outflow of labor is worst in Siberia and Russia's Far East: In January-September 2006 - according to data from the Social Development Ministry - more than 371,800 people (75 percent of them within the 15 to 65 working age range) left these regions.

This "people flight" out of the far east is now becoming a really serious problem since according to Brookings Fiona Hill - in this excellent piece of analysis - while Russia is very rich in physical resources (as well as agricultural land) the Russia suplus labour resources are all to be found in the wrong places. Siberia holds nearly 80 percent of Russia's total oil resources, about 85 percent of its natural gas, 80 percent of its coal, and similar quantities of precious metals and diamonds, as well as a little over 40 percent of the nation's timber resources. According to studies by geographer Michael Bradshaw and economist Peter Westin, with the exception of the city of Moscow and the industrial region of Samara in the Urals, the major contributors to the Russian economy in terms of per capita gross regional product (GRP) are all natural-resource regions, primarily Siberia and the Russian Far East. The oil-producing region of Tyumen in West Siberia tops the list; then Chukotka, also a major energy producer; Sakha (Yakutia), the site of Russia's world-class diamond industry; Magadan, a major mining region; Sakhalin, the island repository off the Pacific coast of one of Russia's richest new finds of oil and gas; and Krasnoyarsk, a vast coal mining, mineral, and precious metal producing region. So the issue of who is actually going to work in these areas in the future is in fact no mean one.

And almost 40 percent of the labor which is available in the Primorye Territory is concentrated in the city of Vladivostok, while the rural and remote areas are facing a population-blight type crisis. The Far East constitutes 30 percent of Russia's total territory, but has less than 5 percent of its population. It has substantial natural resources which could stimulate economic activity and employment, but investors are becoming increasingly reluctant to commit themselves since there is almost no one left to employ there.

The situation in the Russia's Southern Federal District, meanwhile, couldn't be more different. Here labor supply greatly exceeds demand; approximately 20 percent of the working-age population is unemployed. According to the Independent Institute of Socio-Political Studies, for example, only 36,000 people are employed in the Republic of Ingushetia (17 percent of the working-age population, as compared to the Russian average of 74 percent employment rate). Chronic unemployment continues to dog Dagestan, Ingushetia, Kabardino-Balkaria, and Karachayevo-Cherkessiya, where the share of long-term unemployed job-seekers exceeds 65 percent. In Ingushetia, unemployment amongst young people is stuck somewhere around 93 percent mark.

Of course increased inward migration would help mitigate Russia’s growing labor shortage. Russia is already experiencing large migrant inflows, mostly from lower income CIS countries, where working age population is still growing rapidly (such as the Central Asian countries). Migrants are also arriving from China to help ease the labour supply problem in the far East.

According to data from Russia’s Federal Border Guard Service approxiamtely 750,000 Chinese nationals have been legally entering and leaving Russia each year since 2002, about 80 percent of them entering through checkpoints of the Far Eastern Border District. The majority of these workers enter and leave each year, but there are an unknown number who remain behind, and especially among those who did not enter the country legally in the first place.

As Yuri Andrienko and Sergei Guriev convincingly argue in their recent paper "Understanding Migration in Russia", Russia's present migration policy is extremely counterproductive as it both restricts much-needed migration and creates a constant flow of illegal immigrants. Evidently the pressure of its demographic problems mean that Russia will soon have to reconsider its present policy and it is more than likely that it will have to introduce some sort of amnesty for those currently working illegaly in the counrty in the not to distant future. The overall situation is not helped at all by the Russian government's ability to volte face and contradict itself (in the face of xenophobic pressure) on a seemingly regular basis. While attracting immigrants with the one hand, it denies them the opportunity to work with the other. The announcement by Prime Minister Mikhail Fradkov in November 2006 that as of 1 January 2007 the government would be restricting the employment of immigrants in the retail trade sector to 40% of the total was certainly not a constructive move.

However, getting hard numbers on migrant workers in Russia is not easy, and it is important to distinguish between temporary and permanent migrants. As I have already mentioned maybe 750,000 Chinese go to work in Russia on a temporary basis every year, and we know from the Russian migration service that they have just completed an agreement to allow 500,000 or so workers from Uzbekistan to go to work legally in Russia every year. The same sources accept that there are a roughly equivalent number from Tajikstan, and slightly more from both Kazakstan and Ukraine. But as Andrienko and Guriev emphasise, what Russia really needs to compensate for its demographic decline are not temporary migrants, but permanent settlers. In order to adequately compensate for this drop, there needs to be an annual inflow of about 1 million working age migrants the authors estimate, and this is three times the average net rate of inflow which occured in the years between the Censuses of 1989 and 2002. And during this earlier period, of course, we were talking about ethnic Russians returning from the old outposts of the former Soviet Union. Tjiks and Uzbeks may indeed be seen in a rather different light, as already seems to be the case on many a Moscow street.

Rice As An Example of What is a Global Problem

Thailand's benchmark 100 percent B grade white rice was quoted at a record high of more than $1,000 per tonne last Thursday as a result of constrained supply and rising demand as governments in one rice producing country after another consider taking steps to restrain exports. The price was up from around $950 per tonne a week earlier and $383 per tonne in January. Thailand is the world's number one rice exporter and exports almost twice as much rice as India, its nearest rival.

(please click over image for better viewing)

In fact Thailand produces about 22 million tons of milled rice annually and exports about 10 million tons. The sharp spike in prices was produced by a report from a World Bank official earlier in the week, and prices did subsequently fall back again after Finance Minister Surapong Suebwonglee siad reassuring words to the effect that Thailand has no plans to limit rice exports.

``If a key exporter like this limits foreign sales, it would be very much like Saudi Arabia reducing oil exports,'' said James Adams, vice president of the bank's East Asia and Pacific department.

Several of the world's food producers - including Egypt, Vietnam, China and India - have recently placed restrictions and limits on food exports in an attempt to contain domestic prices and to reduce protests from urban consumers. Brazil - which this year should harvest an 11.9 million ton rice crop, up from 11.3 million last season - was busy backtracking at the end of last week on an earlier decision to restrict exports. Brazil's Agriculture Minister Reinhold Stephanes followed the example of his Thai counterpart and stated that Brazil would not, in the end, curb exports. Pakistan is also stepping up to the plate in what has virtually become a global emergency and has stressed it has plans to export 2.5 million metric tons this year, according to farm minister Chaudhry Nisar Ali last week.

Vietnam, however, which is the world's third-biggest rice exporter (after Thailand and India), is going to go ahead and reduce rice shipments by 11 percent this year to 4 million tons to ensure supplies and attempt to curb inflation that is its highest in more than a decade (see more on Vietnam in this post). In doing this Vietnam is following in the footsteps of the world's number two rice exporter - India - whol last month put significant restrictions on the export of rice.

Indonesia, which is the world's third-largest rice producer (as opposed to exporter), also intends to hold back surplus rice from export this year in order to bolster domestic stockpiles, according to President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono speaking on April 18. Export restrictions are particularly threatening to the large rice importers whose populations ofetn depend of the staple for their basic food supply. The Philippines was the world's largest largest importer last year, followed by Nigeria. The Philippines received offers for only two-thirds of the grain it sought to buy on April 17.

Rice is in fact - after wheat - the world's second cereal product. At the beginning of the 1990s, annual production was around 350 million tons and by the end of the century it had reached 410 million tons. World production totaled 395 million tons of milled rice in 2003, compared with 387 million tons in 2002. This reduction in total output which occured around the turn of the century is largely explained by the strong pressure which have been placed on land and water resources, which led to a decrease of seeded areas in some Western and Eastern Asian countries.

Production is geographically concentrated in Western and Eastern Asia, and these retgions now account for more than 90 percent of world output. China and India, between them host over a third of the global population and supply over half of the world's rice. Brazil is the most important non-Asian producer, followed by the United States. Italy ranks first in Europe.

Growth in rice production has, however, been far from linear. Historically, production in ex-Japan Asia has increased steadily but at the end of the 1990s Asian output started to stagnate and in particular in China where rice areas have declined as a consequence of water scarcity and competition from more profitable (oleaginous) crops.

The international trade in rice is estimated between 25 and 27 million tons per year, which is only a very small part (5-6 percent) of total world production., and this makes the international rice market one of the smallest in the world when compared with other grain markets such as wheat (113 million tons) and corn (80 million tons). It also means that the price level is very sensitive to comparatively small changes in the level of exports coming from some key exporters. As can be seen from the chart below, global stocks of rice have declined substantially since the turn of the century. While in part this can be explained by product market efficiencies and the sustainability of lower inventories, it does mean that the sensitivity of the traded rice price to any supply side products has risen considerably of late. Also of note is the way in which stocks of rice have fallen inside China, reflecting the problems the country is having in finding the food to meet the needs produced by the rising living standards of its population (with pressure to transfer land from rice production to other crops or to commercial uses).

(please click over image for better viewing)

Besides the traditional main exporters (Thailand, Vietnam, India and Pakistan), a relatively important but still limited part of the rice which is traded worldwide now comes from developed countries in Mediterranean Europe and the United States. There are two major forces behind this: new food habits in developed countries and new market niches in developing countries.

(please click over image for better viewing)

As we have seen, rapid eceonomic growth across Asia is now putting enormous pressure on food prices. Consumer prices in China, the world's fastest-growing major economy, soared 8.7 percent in February, the fastest pace in 11 years. In Thailand, inflation is running at 5.3% (March) but this is still enough to worry the government, while in Vietnam, inflation jumped to 19.4 percent this month, the fastest pace since July 1995. Vietnamese food prices jumped 30.6 percent from a year ago, with the component including rice leaping 30.1 percent from March 2007 and 10.5 percent from February 2008.

The Food and Agriculture Organization said in February that 36 nations including China face food emergencies this year. World rice stockpiles may total 72.1 million metric tons by end of July, the lowest since 1984, the U.S. Department of Agriculture said.

Prices of agricultural commodities are also being driven by investors looking for alternatives as the dollar and stocks drop. Global investments in commodities rose almost 33 percent to $175 billion last year, according to Barclays Capital. The UBS Bloomberg Constant Maturity Commodity Index of 26 raw materials climbed to a record on Feb. 29 and is up 16 percent so far this year.

But not everyone wants to restrain exports. Rubens Silveira commercial director of Rio Grande do Sul state's Rice Institute said the state - Brazil's No.1 rice grower - should export about 10 percent of this years crop at current prices, and argued that these exports will both help support domestic prices and provide incentives to producers to invest in improving output. Mainstream economists tend to agree with him:

``Limiting exports is pure politics and bad economics since export controls destroy the incentive of farmers to plant more rice,'' Nobel laureate Gary Becker, an economist at the University of Chicago, said in an interview. ``But governments tend to favor the urban workers over the farmers, since urban groups are more politically active.''

And it isn't only rice that is under pressure. Wheat prices are also rising fast. Wheat for July delivery was trading at around $8.1750 a bushel on the Chicago Board of Trade last week, down from the February peak, but still up 62 percent in the past year. Global wheat production is expected to rise 6.8 percent in the 2008-09 season as record prices spur farmers to sow more, the International Grains Council said last week. Wheat output is expected to climb to 645 million tons from 604 million tons this season, according to the London-based council. Inventories are forecast to gain 12 percent to 128 million tons, led by an increase in the U.S.

Global wheat production will advance approximately 6 percent in 2008 over 2007 - to an all-time high of 640 million metric tons - as record prices spur farmers to grow more according to Rabobank estimates. That is 37 million metric tons up on output in 2007 . Plantings will also gain 5 percent and global stockpiles will rise 9 percent they suggest. But then we might like to note that even with a 6% growth rate in output (which is no mean rate of increase) prices have still risen by 62 percent. This gives us some measure of the scale of the problem.

The prices of wheat, corn, rice and soybeans have all risen to record levels this year on shrinking global stockpiles and rising demand from the food, feed and biofuel industries. The rally has meant higher costs for everything from Italian pasta to Japanese noodles, and spurred street protests from Haiti to Ivory Coast.

``We have been neglecting our basic rice production infrastructure and research and development for 15 years,'' said Robert Zeigler, director-general of the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines. ``

India's output is increasing rapidly, but so is demand there, as high rates of economic growth boost incomes. Indian wheat output may climb to 76.8 million tons this year, according to India's agriculture secretary PK Mishra. That's up on the 74.8 million tons estimated in February and up from 75.8 million tons last year. Indian rice output is also expected to rise to a record 95.7 million tons, from the 94.1 million tons estimated on Feb. 7. That's 2.5 percent more than the 93.6 million tons produced a year earlier, but still far from enough to stabilise Indian wholesale prices which are now running at the fastest pace in nearly three years.

Labour Supply

"Thailand has even gone the extra mile to explore additional land for rice production," James Adams, the bank's Vice President for East Asia Pacific, said in a statement.

But with countries as far apart as Ukraine and Thailand (where fertility in each case is already well below replacement level, see here for Ukraine, and here for Thailand) moving to open up more land for agricultural production, we may well want to ask ourselves just where the anticipated manpower is going to come from. Ukraine is already suffering from severe labour shortages as most of its immediate neighbours (and in particular Russia) have sought to resolve their own labour shortage problems by importing Ukrainian migrants. Now the labour shortages back home are producing yet another a massive inflation bonfire:

Since this post is already inordinately long, I am continuing the labour shortage part of this study, in a separate post focusing on Vietnam (which can be found here).

Conclusions

So what is the point - at the end of this very long and tortuous post - that I am actually trying to make here.

Well I think my points would be several.

1/ Firstly and most obviously that the current increase in global commodity prices is NOT simply a monetary phenomenon. Of course it IS a monetary phenomenon, since without he money, as the economic "smart-aleks" likie to point out you can't have the inflation, but it is not SIMPLY a monetary phenomenon, since it is underpinned by profound structural changes in the real economy, structural changes which are taking place on a global scale. Under such circumstances traditional monetary policy is in fact rather limited in its ability to substantially change the situation. Basically the central banks are not as powerful, or as influential, as many seem to think they are, and in particular when globalised money markets mean that traders can leverage funds from one country which is forced to reduce interest rates to meet domestic growth needs (the United States) to supply credit to another where the central bank is busily trying to tighten (India) and where the bottom line in the so-called "carry trade" is set by a Bank of Japan which even during the longest expansion in the country's recent history has proved unable to raise its base interest rate above 0.5% (with few really taking the trouble to ask themselves why this is).

2/. Some of the global imbalances which have been built up over the last half century are now unwinding. In particular some countries which became very poor and very populous in the second half of the 20th century, having now entered their demographic transitions (and see this excellent recent post from Claus for a much fuller exploration of what this really means) are well on the high road to economic development. But due to the specific structure of short term demand as income rises (ie that the marginal propensity of populations in these countries to spend extra income on food) we are seeing important structural changes in some relative prices globally, and the consequences of these changes are quite far reaching.

3/. Almost all countries globally are passing through the Demographic Transition, but countries are at different stages in the process, and in particular some countries have already seen fertility fall sharply below replacement while still remaining economically relatively poor (Eastern Europe and parts of Asia - in particular China, Vietnam and Thailand). This situation really presents us with quite new and complex issues in the context of the rapid rise in the demand for food which the rising living standards which are occuring in these countries is producing. Unlike previous experience in the traditional "demographic dividend" countries, low rural fertility in the above countries means that as young people leave to enter the rapidly growing urban labour market insufficient are left to increase agricultural output at a fast enough rate. Part of the solution to this problem is technological, with increased investment taking place in agriculture, but only part, since as we have seen in developed economies like Spain and the United States which have recently increased their agricultural output, a constant supply of relatively cheap migrant labour has also been necessary. A second solution comes from increasing the relative wages of rural labour (which in its turn of course stimulates technological investment), but then there is no getting away from it, food is going to become relatively more expensive, and this situation is not going to change.

Update

Well at the price of making this already unmanageably long post even more unmanageably long, I will try to keep updating a bit with relevant information. Staring with the fact that the Financial Times today (8 May) had an article about the fact that Chinese companies are now going to be encouraged to buy farmland abroad, particularly in Africa and South America, to help guarantee food security under a plan being considered by Beijing.

A proposal drafted by the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture would make supporting offshore land acquisition by domestic agricultural companies a central government policy. Beijing already has similar policies to boost offshore investment by state-owned banks, manufacturers and oil companies, but offshore agricultural investment has so far been limited to a few small projects.

China is losing its ability to be self-sufficient in food as its rising wealth triggers a shift away from diet staples such as rice towards meat, which requires large amounts of imported feed. China has about 40 per cent of the world’s farmers but just 9 per cent of the world’s arable land. Some Chinese scholars argue that domestic agricultural companies must expand overseas if China is to guarantee its food security and reduce its exposure to global market fluctuations. “China must ‘go out’ because our land resources are limited,” said Jiang Wenlai, of the China Agricultural Science Institute. “It will be a win-win solution that will benefit both parties by making the maximum use of the advantages of both sides.” In the first quarter of this year, food prices in China rose 25 per cent from a year earlier, the highest level of farm inflation since the early 1990s, said UBS.

China is still a net exporter of agricultural commodities but is increasingly reliant on soybean imports and is about to become a net buyer of corn.It imported up to 60 per cent of the soybean it consumed last year and the crop would be a focus of policy support for companies acquiring land overseas, along with bananas, vegetables and edible oil crops, said an official familiar with the ministry’s proposal. The ministry is already talking to Brazil about the possible acquisition of land for soybean, according to this official.

Some countries would find it particularly problematic if Beijing supported Chinese firms to use Chinese labour on land bought or rented abroad – common practice for most companies operating overseas.

Basically, China is not overly rich in surplus rural population, but it does have lots of people trying to farm on inferior quality land who could be "resettled" elsewhere to work more productive land, but on the other hand administrators could be sent out to (for example) Africa to oversee African rural labour working on Chinese projects. Bloomberg also had a piece about a rice project in Tanzania which very possibly is along exactly these lines:

Chongqing Seed Corp., a seed researcher and producer based in southwestern Chongqing city, will plant its proprietary rice in a pilot project in the central African country, a report on China's Ministry of Commerce's Web site said.

China will set up 10 agricultural technology centers in Africa by 2009 under an agreement reached at a November 2006 summit. The Asian country, seeking to tap into Africa's resources, is encouraging its agricultural businesses to expand overseas as its own arable land and water become scarcer.

Chongqing Seed, which also supplies seeds to the Chinese government, will initially plant the crops on a few hundred mu of land in Tanzania next year to promote its products, the statement said. The company has signed a contract for 4,500 mu (300 hectares) of land in the African country, it said.