- The Guardian notes that British citizens of more, or less, recent Irish ancestry are looking for Irish passports so as to retain access to the European Union in the case of Brexit. (Net migration to the United Kingdom is up and quite strong, while Cameron's crackdown on non-EU migrants has led to labour shortages.

- NPR notes one strategy to get fathers to take parental leave: Have them see other fathers take it.

- Reuters notes that the hinterland of Fukushima, depopulated by natural and nuclear disaster, seems set to have been permanently depopulated. Tohoku

- Bloomberg noted that East Asia's populations are aging rapidly, another article noting how Japan's demographic dynamics are setting a pattern for other high-income East Asian economies.

- In Malaysia, the Star notes that low population growth among Malaysian Chinese will lead to a sharp fall in the Chinese proportion in the Malaysian population by 2040.

- Coming to Alberta, CBC notes how the municipality of Fort McMurray has been hit very hard by the end of the oil boom, as has been Alberta's largest city and business centre of Calgary.

- On the subject of North Korea and China, The Guardian wrote about the stateless children born to North Korean women in China, lacking either Chinese or North Korean citizenship.

- The Inter Press Service notes that, as the Dominican Republic cracks down on Haitian migrants and people of Haitian background generally, women are in a particular situation.

- IWPR provides updates on Georgia's continuing and ongoing rate of population shrinkage, a consequence of emigration.

- On the subject of Cuba, the Inter Press Service reported on Cuban migrants to the United States stranded in Latin America, while Agence France-Presse looked at the plight of Cuba's growing cohort of elderly.

Monday, March 14, 2016

Some followups

For tonight's post, I thought I'd share a few news links revisiting old stories

Wednesday, March 09, 2016

On women and fertility, briefly

Thinking about Demography Matters and International Women's Day, I realized that almost all of my blogging here on fertility issues, at least the blogging that relates to the incentives and disincentives, relates to the choices of women. This makes a certain amount of sense since it's ultimately women who are essential in reproduction--not biologically, true, but socially. Single motherhood is more common than single fatherhood, at least in contemporary Western societies, for a reason.

This is not going to be a very long post at all. Consider it a brief note, to myself as much as to you. What are the hidden assumptions in the relationship between gender--female gender, male gender--and demographic outcomes? What things get missed?

Friday, March 04, 2016

Some thoughts on the demographics of Japan and path dependency

I learned from any number of sources, from E-mails and from blogs and from the "News" section of my Feedly news feed, that the demographics of Japan have entered a new phase. The population is now in sharp decline. From the CBC:

Japan's latest census confirmed the hard reality long ago signalled by shuttered shops and abandoned villages across the country: the population is shrinking.

Japan's population stood at 127.1 million last fall, down 0.7 per cent from 128.1 million in 2010, according to results of the 2015 census, released Friday. The 947,000 decline in the population in the last five years was the first since the once-every-five-years count started in 1920.

Unable to count on a growing market and labour force to power economic expansion, the government has drawn up urgent measures to counter the falling birth rate.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has made preventing a decline below 100 million a top priority. But population experts say it would be virtually impossible to prevent that even if the birth rate rose to Abe's target of 1.8 children per woman from the current birthrate of 1.4.

Without a substantial increase in the birthrate or loosening of staunch Japanese resistance to immigration, the population is forecast to fall to about 108 million by 2050 and to 87 million by 2060.

Bloomberg went into more detail.

Tokyo, Japan’s capital, had the highest municipal population with 13.5 million. The city also recorded the biggest increase in population after Okinawa prefecture. Osaka, the country’s second biggest city, is among 39 prefectures and cities that had a decline in population.

The ratio of Japan’s 1,719 municipalities that had a drop in population expanded to 82 percent in 2015, from 77 percent in 2010. The number of households rose 2.8 percent to 53.4 million with the number of people per household dropping to 2.38 from 2.46 over the five-year period.

Statistics Japan's latest estimates estimate a decline of nearly 200 thousand people between the 1st of September, 2015, and the 1st of February of this year. This Japanese-language PDF apparently goes into more detail about the particulars.

Tokyo, the reports note, continues to grow on the balance of net migration, but away from Tokyo decay is real. I would again like to recommend to our readers Tokyo-based blogger Richard Hendy's sadly inactive blog Spike Japan, a compilation of tours throughout different Japanese regions which have entered terminal or near-terminal declines, something that he plausibly enough blames on demographics. With fertility rates far below replacement levels, large-scale migration of the young out of declining areas, the rapid aging of the remaining population, and next to no foreign immigration, it's difficult to imagine how some peripheral areas could ever be revived.

It's increasingly difficult to imagine how Japan as a whole will revive. Jacob M. Schlesinger's November 2015 Wall Street Journal "Tokyo’s Test: Policy vs. Demographics" noted the challenge for the country.

In May 2012, [Masaaki Shirakawa, the governor of the Bank of Japan from 2008 through 2013] delivered a widely cited speech titled “Demographic Changes and Macroeconomic Performance: Japanese Experiences.” In it, he cited global evidence that “the population growth rate and inflation correlate positively,” a finding he called “a sharp contrast with the recently waning correlation between money growth and inflation.” In other words, a country like Japan with a shrinking population was inevitably condemned to slow growth and deflation, and central banks were impotent to fight it.

[. . .]

Just over two and a half years into his term, [new Abenomics-era governor Haruhiko Kuroda] has delivered well on the first pledge, with two rounds of “quantitative and qualitative easing” that more than doubled the BOJ’s asset-purchase plan used to create fresh liquidity. The jury is still out on his second pledge, to end deflation and revive Japan’s economy.

The bad news: Japan’s gross domestic product contracted for the two consecutive quarters ended Sept. 30, pushing the country into recession for the second time during Mr. Kuroda’s brief term. Some of that results from cyclical problems and policy missteps outside Mr. Kuroda’s control: the slowdown in China, an ill-timed sales tax hike. But some stems from the fact that economy’s capacity to expand is constrained when the workforce is shrinking, making recessions much more common.

The battle to break deflation has also struggled, due both to falling oil prices and the slow growth that has damped price pressures. After some early success in pushing the most closely watched inflation gauge above 1%, deflation returned over the summer, and the Japanese government reported Friday that the consumer-price index was negative in October for the third month in a row.

But the BOJ released Friday its own preferred measure—stripping out prices for food, energy and other items that the central bank considers distorting of underlying trends—that showed inflation rising in October at a more robust positive 1.2% annual rate. The aggressive monetary policy has also helped create the tightest job market in a generation, with a separate Friday report showing the unemployment rate dropping to an eye-popping 3.1%. That, in turn, has helped expand the labor market by prompting employers to find more ways to use older workers conventionally considered past retirement age. The jump in employment in Japan by those 65 years and older has kept the size of its labor force fairly stable, even as the classically defined “working-age population” has contracted. Whether Japan’s newly aggressive monetary policy can really overcome the demographic drag hinges on whether Japanese companies can be persuaded to invest more at home. An economy’s ability to grow is rooted in the expansion of its labor force, combined with the ability to boost its labor productivity, or output per worker. Productivity can be lifted by investment in labor-enhancing equipment.

Could this investment be enough? It depends, Schlesinger concludes, on the Japanese government being able to successfully alter the perceptions of business about the dire business environment. Whether or not this is achievable, particularly in the context of Japan's increasingly adverse demographics, is another issue entirely. Yes, it's possible that Japan might successfully implement a partial roboticization of its economy to cope this these challenges. Whether the technological improvements necessary will arrive in time is another question entirely.

How is Japan dealing with its demographics issues? Not very well. See Isabel Reynolds' October 2015 report noting that Abe's proposed policies for dealing with Japan's demographic issues have not been successful: substantial immigration remains impossible, child care and elderly care programs are not funded to meet the demand, women and especially mothers have substantial problems in the work force, Japan's population continues to drift towards Tokyo Metropolis. A scandal recently erupted over paternity leave, when parliamentarian Kenzuke Miyazaki was criticized for taking paternity leave and then resigned following revelations of an affair. Traditional gender norms seem to still be in effect, removing any possibility of change, certainly any hope of the Nordic-like near-replacement fertility wanted by Abe. Japan's immigration policies, as the report of Bloomberg's Yoshiaki Nohara and Jie Ma about Japan's much-criticized foreign-technical internship program illustrates, remain exploitative, and seem likely to deter immigration.

Back in 2010, Hendy wondered if Japan was stuck in a downwards spiral.

It might just be, however, that despite recent evidence to the contrary, Japan has embarked on a vicious demographic spiral, in which a variety of complex feedback mechanisms set to work: aging results in declining international competitiveness, which results in greater economic hardship at home, which results in a suppressed birthrate; aging results in ballooning fiscal deficits, which in the absence of debt issuance must result in higher taxes or cuts to government spending, which cause economic pain, driving down the birthrate; aging, as the elderly dissave, results in a decline in the pool of domestic savings on which government borrowing is an implied claim, reducing room for fiscal maneuver and resulting in less ability to withstand exogenous shocks; aging further entrenches conservative attitudes to everything from pension reform to immigration, resulting in greater government outlays and smaller government receipts; aging leads the electorate to fear for the future of the pension system, resulting in more saving by the economically active, depressing consumption, which drives manufacturers offshore and raises unemployment, which is strongly correlated with the birthrate.

I would argue that we are seeing just this sort of thing. Certainly the downward demographic spiral is continuing, with inadequate signs as of yet that Japan is going to be making the cultural and institutional changes needed to foster a revival in fertility rates. The new normal in Japan might well be low overall fertility, some people having only small families, some opting not to have children together.

Even if there was a miraculous revival tomorrow to replacement-level fertility, there would still be a huge trough in Japanese demographics, a lack of potential workers and consumers, that could only be plausibly filled by immigration. There, too, Japan is lacking. I have blogged here about the example of South Korea, where the total stock of foreign-born residents is not only comparable to that of Japan despite South Korea's population being only 40% of the size, but where the national government is actively encouraging immigration. Would radical change be enough? Japan could have been a destination for migration flows for some time--I remember reading in the English translation of Robert Guillain's The Japanese Challenge about how some industrialists wanted to bring in Taiwanese guest workers as early as the 1960s--but Japan has explicitly chosen to deter migration. In this context, networks of migrants and migration have formed without Japan, potentially leaving it outside. Might Japan open the doors and find out that the people who might otherwise have come to Japan opted for the more familiar Korea, or China, or who knows where else instead? It's possible.

How can Japan escape its demographic trap, break from its existing path? I straightforwardly admit bafflement. I only hope that the people running one of the world's largest economies will do better than me.

Wednesday, March 02, 2016

On Brexit and how limited free movement in the Commonwealth is a poor substitute for the EU

A couple of weeks ago at my blog, A Bit More Detail, I linked to an interesting article about the legacies of the First World War and the thin ties of the Commonwealth at The Conversation. There, James McConnel and Peter Stanley describe how a British-Australian dispute over commemorating a battle of the First World War, the Battle of Fromelles, brings our contemporary nationalisms into conflict with the imperial-era reality of a much closer and more complex British-Australian relationship of a century ago. There was no clear division between Briton and Australian.

Awareness of the historical context of the battle has clearly informed some British coverage of the decision by the Australian Department for Veterans Affairs to invite only the families of Australians to the memorial ceremony this year. Coverage in the UK has suggested that “banning” the relatives of the 1,547 British casualties of Fromelles, exclusively focuses on the Australian soldiers lost in light of the smaller, but still significant, British casualties.

In response, an Australian spokesman noted in The Times (paywall) that Britain’s own Somme commemoration of July 1 2016 will only be open to British citizens. It’s clear the war’s centenary is being shaped by modern national and state agendas.

But there is an anachronism at the very heart of this spat because – as the military historian Andrew Robertshaw said: “A surprisingly high proportion of the Australian Imperial Force were not actually born in Australia.”

Many of the Australian volunteers, the authors go on to explain, were themselves recent migrants from the United Kingdom, still feeling many loyalties to the country of their birth. At a time when the nationhood of Australia--arguably, like that of the other settler colonies of the British Empire--was far from established and issues of citizenship and identity were uncontestedly unsettled.

Among the names included under the headline “Australian casualties” in The (Melbourne) Argus of August 22 1916 was that of Private Charles Herbert Minter. He was just one of 5,513 soldiers of the AIF who had been killed, wounded, or captured during the bloody attack on Fromelles of July 1916.

Minter was born in Dover, in the English county of Kent, in 1888. He arrived in Australia in October 1910 at the age of 22 and enlisted less than five years later in the Australian Imperial Force in July 1915. In doing so, he was typical of many of the so-called “new chums” (as recent arrivals from Britain were colloquially called). One estimate suggests that 27% of the first AIF contingent were British born, with estimates for the war as a whole varying between 18% and 23%.

Australia was hardly unusual among the Dominions in this respect – 26% of the first contingent of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force were British born, while 64% of the first contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force had been born in Britain. As one of these men commented years afterwards: “I felt I had to go back to England. I was an Englishman, and I thought they might need me.”

That Minter’s British descendants (his “sorrowing sister” posted a death notice in tribute to her “dear brother” in the Dover Express in August 1916) would not technically be eligible to attend the Fromelles commemoration highlights the way that the multi-layered identities of these British-born “diggers” (and “Kiwis”, and “Canucks”) have been rendered one-dimensional in the century since the guns fell silent.

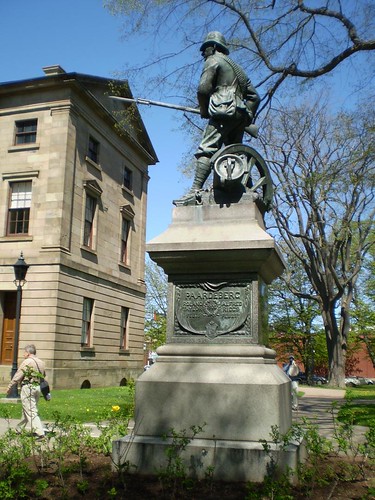

My own personal background, and that of my native province of Prince Edward Island, is not nearly as closely tied to the United Kingdom. The last of my ancestors arrived on the far side of the Atlantic Ocean from Europe in the 1850s. The legacies of the British Empire, of the blood shared in common ancestry and spilled in wars, are still ubiquitous. Never mind the matter of ancestry, of Canada's domination by descendants of migrants from the British Isles, never mind even the great cenotaphs to the dead in the world wars. In Charlottetown, just around the corner from the provincial legislature and in front of the courts, stands a monument to the now forgotten Boer War battle of Paardeberg, waged in 1900. Only after I took a photo of this monument in 2008 did I learn about this battle, once so important to Prince Edward Islanders as to deserve a prominent memorial.

It's still up in 2014.

The British Empire was a reality. It is no longer. In the case of Canada, the repatriation of the Canadian constitution that was completed in 1982 definitely established Canada as a state fully independent from the United Kingdom. All of the other erstwhile colonies, whether destinations for British migrants or not, have gone through similar processes. The Commonwealth of Nations has some meaning, particularly inasmuch as our head of state is shared with more than a dozen other countries and as the organization that gives its name to a sporting event of some note, but that's it.

There are some who would like to change this, who would like to establish unfettered freedom of movement between at least some of the Commonwealth realms. In recent years, it has been the subject of some discussion, talked about in March 2015 at Marginal Revolution, and reported by Yahoo in November 2014.

Canadians who want to live or travel in the United Kingdom could be granted the ability to do so without the current shackles of visa requirements and limitations, should the British parliament heed the call of a British think-tank.

That call involves urging for the creation of a vast “bilateral mobility zone” that would give citizens of the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and Canada the ability to travel freely, without the need for work or travel visas, between those Commonwealth nations.

"We want to add distinct value to Commonwealth citizenship for those who wish to visit, work or study in the U.K.," reads the report released by the Commonwealth Exchange. "The Commonwealth matters to the U.K. because it represents not just the nation’s past but also its legacy in the present, and its expanded potential in the U.K.’s future."

The idea of easier mobility between Canada and some of its closest Commonwealth allies would be an exciting concept. There are currently 90,000 Canadian-born residents of the U.K., and another 34,000 living in Australia and New Zealand.

The Commonwealth Exchange report takes on the larger question of the U.K.’s place on the international stage, noting that while the economies of European Union members are struggling, the Commonwealth nations such as Australia and India are booming. Despite this, its connection to those countries is weakening.

This is an unlikely outcome. As the CBC noted in its reportage, there just is too much that is vague about the proposal, and from the Canadian perspective not enough to gain.

“I think it’s an intriguing proposal, but I think chances are it will be some years in the making if it’s ever to be realized,” said Emily Gilbert, an associate professor who teaches Canadian studies and geography at the University of Toronto.

“So I don’t know where the political will would be coming from to get this going.”

Gilbert said allowing greater mobility is a worthy goal, but much depends on the specifics of the agreement between the countries.

Would immigrants automatically gain permanent resident status or have full access to citizenship rights, for example, beyond simply having the right to work and stay indefinitely?

“If they were to move ahead with this, that is what would be worked out, and the devil is in the details,” she said.

Jeffrey Reitz, from the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs, said the chance of seeing such an “eccentric” agreement between the four countries is effectively zero.

He said it’s unclear why Canada would pursue a proposal with New Zealand, Australia and U.K. instead of the U.S. and Mexico, countries that are already part of a free trade agreement. Or why not a proposal to loosen travel between all 53 Commonwealth countries?

The Commonwealth Freedom of Movement Association ranks highly on Google. In its blog, one author argues that expanding this four-country zone to include other candidates--like Jamaica, an Anglophone island nation not much different from New Zealand in size, or a South Africa that has as large a natively Anglophone population--would create the risk of too much migration. In all honesty, with the exception of the noteworthy migration of New Zealanders to Australia, I'm not sure that there are any especially significant ongoing flows of migrants between these four Commonwealth realms. Is there much of an untapped potential for migration? All four countries are already high-income countries with comparable standards of living. Is there any particular point to this?

There actually is, but it is not related to gains from migration. With this, we come back to what I talked about here in July 2012, about the idea of liberalized migration between certain Commonwealth realms serving as a supposed substitute for Britain's participation in the European Union's unified labour market. The idea of a Canadian migrant to some Britons would be substantially more appealing than the idea of a Polish migrants, partly because of the assumption of shared ancestry but also because such might be the first step towards Britain's ascent to non-European prominence. Nick Pearce's essay "After Brexit: the Eurosceptic vision of an Anglosphere future", published last month at Open Democracy, sets the stage for the Anglospheric dreams of many in the United Kingdom.

In the last couple of decades, eurosceptics have developed the idea that Britain’s future lies with a group of “Anglosphere” countries, not with a union of European states. At the core of this Anglosphere are the “five eyes” countries (so-called because of intelligence cooperation) of the UK, USA, Australia, Canada and New Zealand. Each, it is argued, share a common history, language and political culture: liberal, protestant, free market, democratic and English-speaking. Sometimes the net is cast wider, to encompass Commonwealth countries and former British colonies, such as India, Singapore and Hong Kong. But the emotional and political heart of the project resides in the five eyes nations.

[. . .]

As Professor Michael Kenny and I set out in an essay for the New Statesman, the Anglosphere returned as a central concept in eurosceptic thinking in the 1980s, when Europhilia started to wane in the Conservative Party and Thatcherism was its ascendancy. On the right of the Conservative Party, we argued:

“…American ideas were a major influence, especially following the emergence of a powerful set of foundations, think tanks and intellectuals in the UK that propounded arguments and ideas that were associated with the fledgling “New Right”. In this climate, the Anglosphere came back to life as an alternative ambition, advanced by a powerful alliance of global media moguls (Conrad Black, in particular), outspoken politicians, well-known commentators and intellectual outriders, who all shared an insurgent ideological agenda and a strong sense of disgruntlement with the direction and character of mainstream conservatism.

[. . .]

The idea of the Anglosphere as an alternative to the European Union gained ground amongst conservatives in their New Labour wildnerness years, when transatlantic dialogue and trips down under kept their hopes of ideological revival alive. It was given further oxygen by the neo-conservative coalition of the willing stitched together for the invasion of Iraq, which seemed to demonstrate the Anglosphere’s potency as an geo-political organizing ideal, in contrast to mainstream hostility to the war in Europe. By the time of the 2010 election, the Anglosphere had become common currency in conservative circles, name checked by leading centre-right thinkers like David Willetts, as well as eurosceptic luminaries, such as Dan Hannan MEP, who devoted a book and numerous blogs to the subject.

As Foreign Secretary, William Hague, sought to strengthen ties between the Anglosphere countries, despite the indifference shown by the Obama presidency to the idea. After leaving the cabinet, the leading eurosceptic Owen Patterson gave a lengthy speech in the US on the subject of an Anglospheric global alliance for free trade and security; he could expect a sympathetic hearing in Republican circles, if not the White House. And in its 2015 election Manifesto, UKIP praised the Anglosphere as a “global community” of which the UK was a key part.

I'll note now, just as I did four years ago, that all this is terribly unlikely, at least in Canada. I am personally unaware of any significant political group that would sign on to this particular structure. The Commonwealth unification movement is dead. Canada is an independent state with its own interests, many of which do not follow the patterns of pro-Brexit Anglospherists. Indeed, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has stated Canada's preference for a United Kingdom that remains engaged within the European Union. The United Kingdom could still liberalize its visa procedures with as many Commonwealth realms as its government might like within the European Union, what with the continued fragmentation of the European Union's migration policies. The United Kingdom could always have chosen to leave the doors to its erstwhile colonials open.Quite frankly, many Canadians might prefer the United Kingdom to remain within the European Union in the case of such a liberalization.

I'll also note my skepticism of the motives of many of the proponents. Why include New Zealand but not Jamaica within this scheme? Jamaicans, as a community and as individuals, are far more likely to benefit from this liberalization than New Zealanders? If some people within the United Kingdom want to radically shift immigration policy, why not perhaps try to replace Poles with Jamaicans? The answers are obvious, and unflattering. The chief one is that these people do not want many immigrants at all, perhaps particularly the "wrong" type of immigrants. The pro-Brexit Anglospherists who offer up the idea of free migration with the richest and whitest of the old colonies could be accused of bait-and-switch, of wanting to exit a European Union where migration is a substantial presence for a mini-Commonwealth where migration is, if not less of an issue, more politically difficult. (What immigration policies, I wonder, are Canada and Australia and New Zealand supposed to adopt?) I'd accuse some of these of having hidden motives, but then some of them are quite open about their plans.